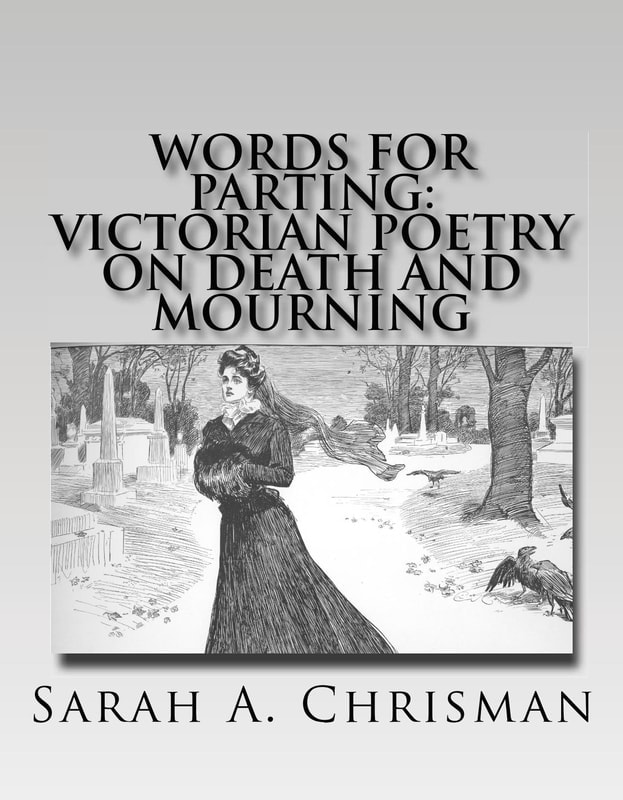

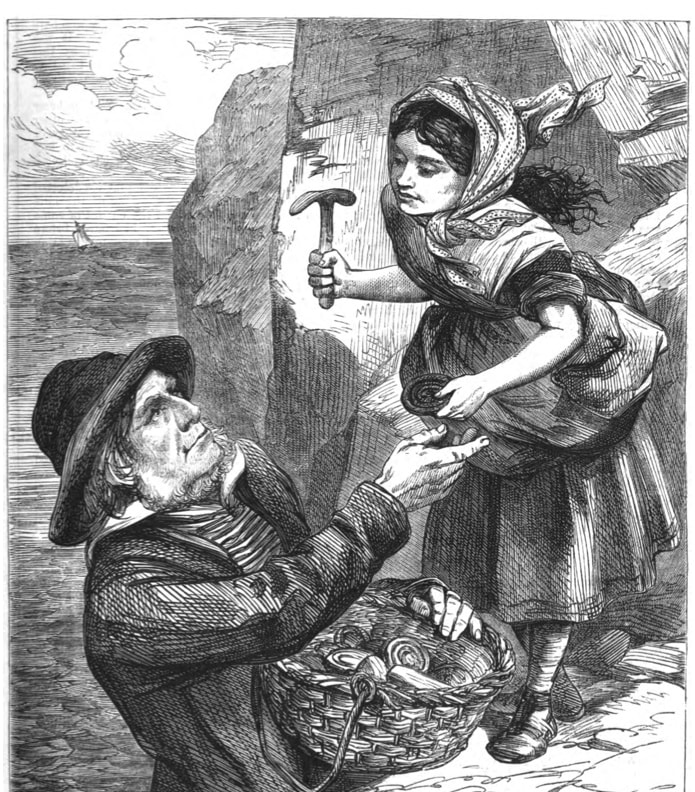

Words For Parting Love and grief and the two most private, and at the same time the most universal of all human emotions. It is for love that we remember the dead: love of their spirits, love of their vibrancy, love of the good deeds which they did and which live on after them. The poems in this collection were all written by grieving hearts who have now themselves passed over into that great mystery. We can not truly know what death is, yet we know it will come to all of us. In ancient times when a friend told the philosopher Socrates that his judges had sentenced him to death he responded, "And has not Nature passed the same sentence on them?" "…Go to a typical American elementary school a day or so before Hallowe’en and ask a classroom of schoolchildren to draw a ghost’s house. If our culture simply associated ghosts with any general group of people who have passed on, one would expect a broad range of dwellings to be represented in the children’s drawings, representing a span across human history: caves, huts, castles, etc. Yet it’s rare for our culture to conjure these as their first impulse picture of a ghost’s abode. With the possible exception of classrooms in certain New England communities, I expect that even an eighteenth-century home would be the exception rather than the rule in the drawings produced by our theoretical class of children—with most of the boys and girls happily sketching away at nearly identical images of decayed Victorian mansions while one or two immigrant children wondered why their classmates’ drawings had such a striking uniformity. Their puzzlement would be entirely legitimate. After all, why isn’t an American’s first thought when they hear the word "ghost" an eighteenth- or a seventeenth-century specter? If it’s simply a matter of accessibility and familiarity, why don’t we think of twentieth-century ghosts? It’s not as though no one died in the past hundred years. There is an immense amount of cultural baggage tied up with the idea of a haunted house, and nearly all of the images first appearing when the phrase is invoked are Victorian in nature. Simply utter the words "haunted house" and the average American mind instantly conjures up a silhouette of a Queen Anne mansion with crumbling gables and a small graveyard to the side, the whole scene backlit by a huge harvest moon. Few would associate the term with a 1950s rambler or a tract house quite so quickly, no matter how many grisly murders had been committed there… How did such lovely examples of architecture as Victorian houses become associated with dead people who can’t make up their minds about an afterlife? Culturally speaking, much of the ectoplasmic trail can be followed back to the economic depression of the 1930s. At that time, Victorian buildings were seen as white elephants: embarrassing remembrances of a more affluent time. No one could afford their upkeep any longer and they were thus left to rot and become infested by unpleasant creatures making frightening sounds in the dark. As disenfranchised people wandered the country looking for work and scraping for food, they hated these empty reminders of an ancestral prosperity and dignity now lost, with their broken windows that leered like the disapproving eyes of the dead. The New Yorker cartoonist Charles Addams illustrated the spirit of that discomfort in his Addams Family drawings, macabre caricatures of ghoulish creatures living amid decayed Victorian settings. In doing so, he cemented these images in the American subconscious for decades to come. It can be quite interesting to see how modern purveyors of the macabre take advantage of this permeating connection lingering in our minds…" --This Victorian Life, Sarah A. Chrisman *** |

Archives

June 2024

Categories |

***

RSS Feed

RSS Feed