We've just returned from a grand adventure!

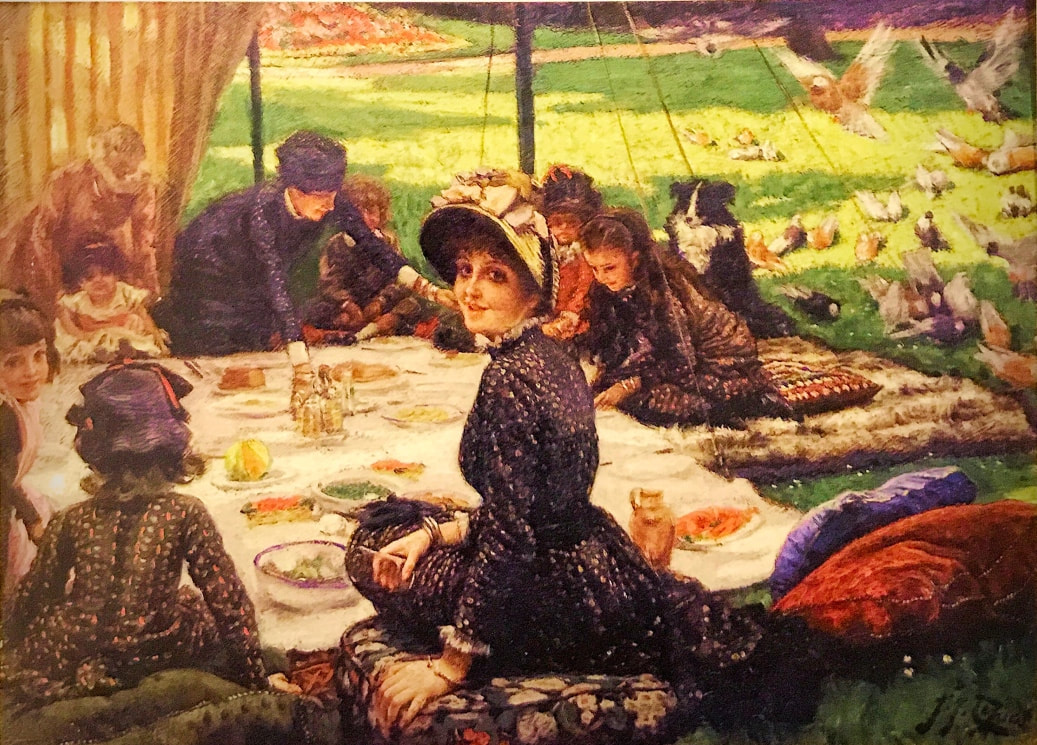

A few months ago we received an invitation to speak at the Belle Meade Plantation near Nashville, Tennessee, an absolutely gorgeous place with a very rich history. Naturally we accepted with pleasure, and we looked forward to it with great anticipation. Neither of us had ever been to Tennessee before —indeed, the farthest south either of us had ever travelled was Maryland. Before we left we were very curious as to what it would be like, and then throughout our trip we were delighted to see Southern hospitality living up to its warm reputation in the best ways possible.

When we arrived in Nashville our host Andy greeted us with a beautiful bouquet of yellow roses and Gebera daisies (both flowers symbolizing friendship), then he took us to supper at a classic southern restaurant called the Loveless Café, which is famous for its biscuits. While we ate we enjoyed hearing Andy's insights into Southern history, and sharing Pacific Northwest history with him. When we left the restaurant it was snowing outside, which surprised us quite a bit but was beautiful to see. As Andy took us through Nashville and the surrounding area he pointed out the city's replica of the Parthenon, Belle Meade where we'd be speaking, and a beautiful home called West Meade, which used to be part of the Belle Meade estate but is now a private residence.

Throughout our trip I kept privately marveling at the rich diversity of the English language as it is spoken in different regions. Hearing my own out-of-place Northwest accent against the background of all the lovely Southern tones around us, I reflected how extraordinary it is that a single language can sound so very different, yet still be mutually comprehensible to its speakers. From time to time I would recall how various readers have told me I should create an audiobook version of my Tales of Chetzemoka, but I've always replied that I didn't think I could replicate Nurse McCoy's accent: now I know I can't. If I tried to wrap my clumsy northern mouth around any Southern accent (let alone McCoy's Appalachian one), I would make such a hash of things I would deeply embarass myself and probably offend every last one of my Southern readers.

On our first morning in Nashville Andy took us to Centennial Park and we toured the Parthenon. Originally built as a temporary structure for the 1897 Tennessee Centennial Exposition, it was so popular with the city's residents and visitors that when it started to crumble in the 1920's it was fully restored with permanent materials. The structure is a full-scale replica of the Ancient Greek temple devoted to Athena, goddess of wisdom, and stands as a symbol of Nashville's reputation as the Athens of the American South.

Ancient records report that the original Parthenon in Greece held a statue of Athena crafted by Pheidias in the 5th century B.C., but sadly it no longer exists. Enough records were made of it, though, to recreate the enormous statue and she proudly stands within the Nashville replica of her temple: 41'10" tall, gilded with 8 lbs of nearly pure gold, and holding a 6'4" statue of Nike, goddess of victory, in her right hand. Looking on it, I thought of John Ruskin's book The Queen of the Air, which describes how the philosophies of Ancient Greece (and especially the ones associated with Athena) remain relevant throughout the ages.

"The Spiritual power associated with [Athena] is of two kinds: first, she is the Spirit of Light in material organism; not strength in the blood only, but formative energy in the clay; and, secondly, she is inspired and impulsive wisdom in human conduct and human art, giving the instinct of infallible decision, and of faultless invention." —John Ruskin, The Queen of the Air, 1869, p. 59.

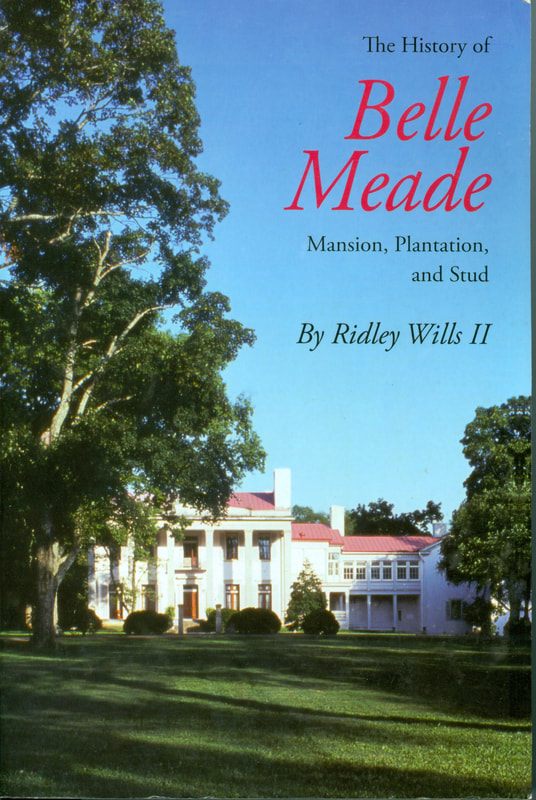

After leaving the Parthenon we headed to Belle Meade. It's a Southern Plantation on a grand scale; although the acreage on which it is located has dwindled (once encompassing 3500 acres, the land holdings of Belle Meade have decreased to little more than the immediate grounds around the buildings), its beauty remains. Around the mansion, groomed fields with a wonderfully civilized creek running through them present an idyllic location.

Originally founded in the early 19th-century, Belle Meade's first owner John Harding built a wooden cabin to reside in while his large brick mansion was under construction. (Remember the cabin: there'll be more on it later.) The land at Belle Meade produced a variety of products, but by the Victorian era Belle Meade was developing a reputation for one thing in particular: breeding magnificent thoroughbred race horses. In 1860 William Giles Harding (the owner of Belle Meade) had more silver trophies and horse racing cups than anyone else in America. Although there are no horses at Belle Meade today, the bloodlines established there continue to win prizes: every horse which has raced in the Kentucky Derby since 2003 (both winners and losers) are descended from Belle Meade stock.

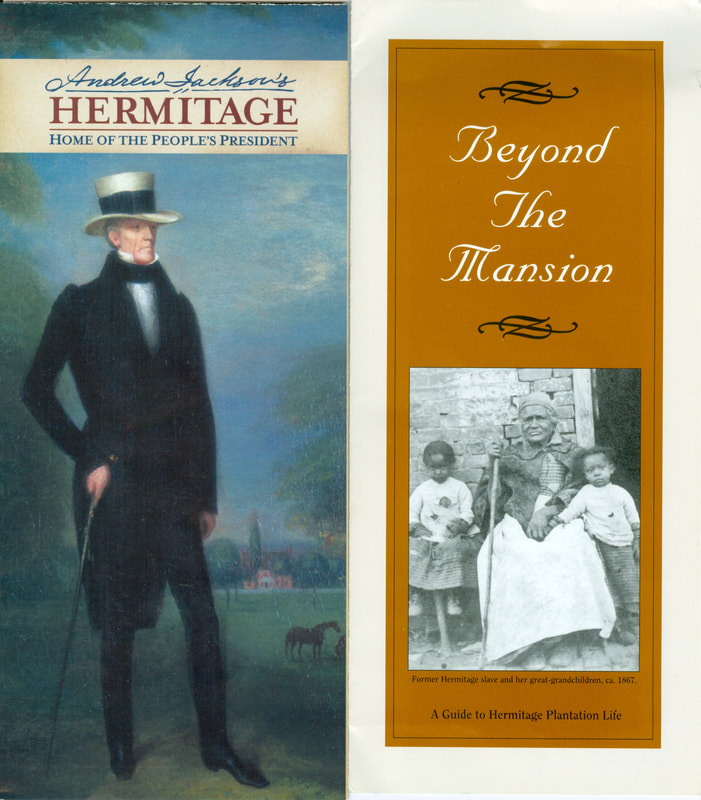

In Antebellum times the labor which ran Belle Meade (including caring for, training and racing those beautiful race horses) depended heavily on the work of enslaved people. After construction was completed on the mansion, the original wooden cabin became a residence for high-ranking slaves. The structure consists of two rooms connected by a dog-trot, and the modern museum has set up the exibit in a very clever way: one room is furnished as it would have been when the property's owners were living there, awaiting the completion of their mansion, and the other room is set up with furnishings consistent with the building's long use as the residence of Bob Green, Belle Meade's chief hostler. Bob Green was brought to Belle Meade as a slave in 1839[1], and continued working there as a freeman after the end of the Civil War.

[1] Source: Miller, Andrew B. et al. Meet Me At The Belle Meade Plantation, Southwestern Publishing Group, Inc. 2014, p. 70.

When we moved on to a tour of the Belle Meade mansion, Gabriel particularly enjoyed seeing the different ways Southern architecture deals with the challenge of summer heat: the enormous doors and windows which could be thrown open for ventilation, the soaring ceilings higher even than the most impressive ones we have up north. The decor in the mansion was both beautiful and tasteful, and above all it represented the driving passions of those who lived there. As mentioned above the family who built and ran Belle Meade made their fortune by breeding horses, and their well-deserved pride in their stock is visible everywhere: in the iron horse heads which flank the gates on the driveway, in the myriad portraits of prize-winning equines which cover the walls of the front hall where visitors enter. We saw a portrait of a mare named Gamma along with a silver cup she'd won in a race, then we heard the story of how she'd surprised everyone by giving birth to a foal immediately after winning it!

Even the dining room at Belle Meade has printed pictures of horse races on its walls. In General Jackson's office atop the beautiful desk where he kept accounts one sees a particularly vivid example of the inseparable connection between Belle Meade and prize winning horses: a pair of inkwells made from a pair of hooves. They belonged to Iroquois, the first American horse to win the English Derby —quite a feat, since he had to learn to run a racetrack in the opposite direction from the way he'd been trained back home in America. He also won the Epsom Derby, among other British races. After his illustrious racing career he lived a pampered life at Belle Meade until he passed away of natural causes.

Famous animals are generally far better known than the humans who made them celebrities. (Anyone who doubts this should try to recall the name of Grumpy Cat's talent agent without looking him up.) The Belle Meade horses would not have achieved such reknown if not for the efforts of the various African American jockeys and trainers who worked with them; Bob Green's story is fairly well documented but the names of many of the men who worked under him have been forgotten. Some of their pictures have been preserved, though: on the edges of many of the portraits of the famous race horses are the trainers and jockeys who made them what they were. The museum's staff has undertaken the challenging but extremely laudable project of identifying these men and bringing their stories to light. Each of these men is an important thread in the tapestry of Belle Meade's history, and it's wonderful that the staff is trying so hard to learn more about them. Anyone who has ever tried to identify an individual from little more than an aged photograph can appreciate the difficulty of the project, and I wish them the best of luck with it.

Horses made Belle Meade famous, but there is far more to see there than relics of equines. In the library are charming little details of life ranging from a family Bible to a small piece of artwork made of painted spiderwebs. Upstairs are the bedrooms where the Hardings and their visitors slept. I generally don't subscribe to the "Great Men / Women of History" approach to the past but I do have a soft spot in my heart for Frances Cleveland, the First Lady who was instrumental in implementing kindergarten education for the poor in the U.S, and who was known in her time as America's darling. I couldn't help feeling a bit moved when I saw the bed where she had slept when she and her husband stayed at Belle Meade during a presidential visit. It is an absolutely gorgeous piece of furniture; the frame and canopy are richly carved wood, embracing silken bedclothes. Frances Cleveland must have looked like an enchanted princess from a fairy tale when she slumbered there. (When Bob Green was introduced to the Clevelands, like many who met that couple he was proud to have shaken hands with a president but far more impressed with Frances, who he enthusiastically declared was a true queen.[1]) A journalist recounting the Clevelands' visit in 1887 described Belle Meade as "an epitome of homely luxury and comfort, spacious, genial and unostentatious, though elegant, just such a place as even so distinguished a guest would select for quiet repose."[2] The description seems just as apt today.

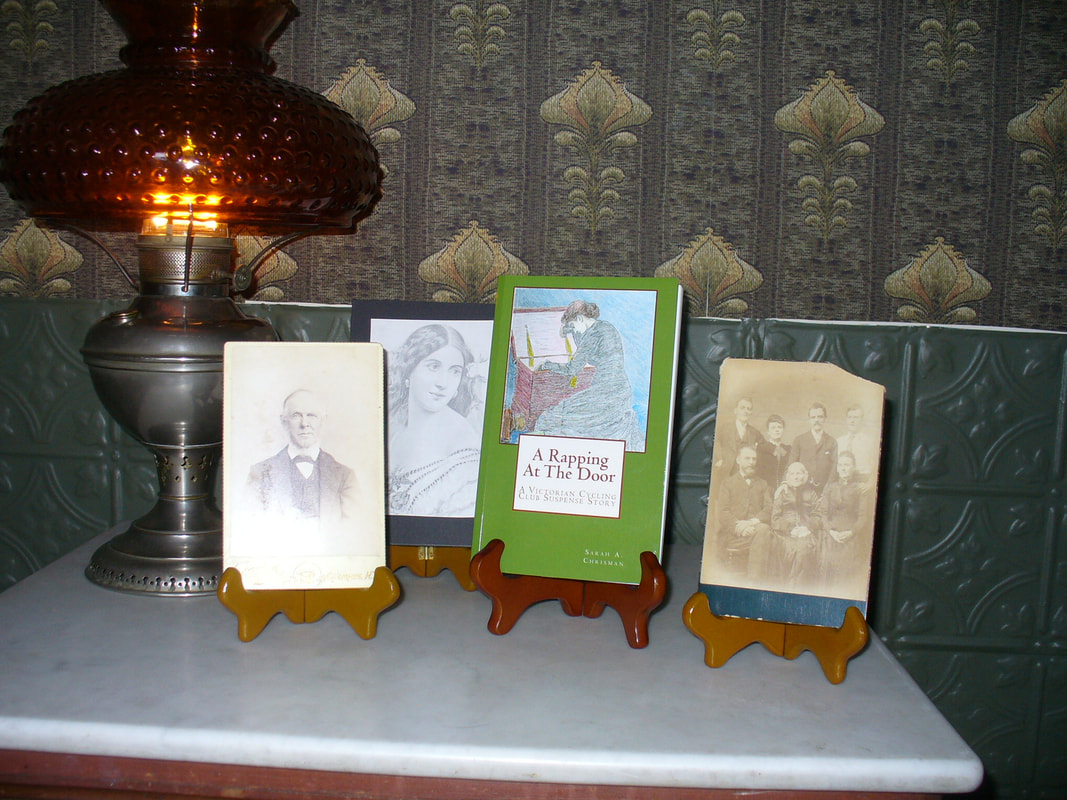

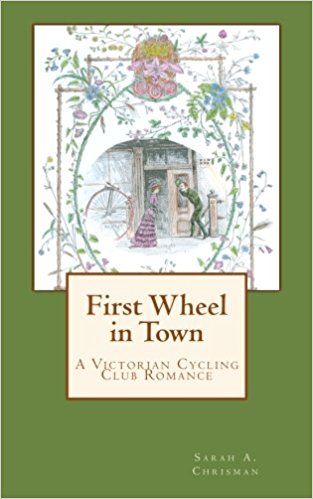

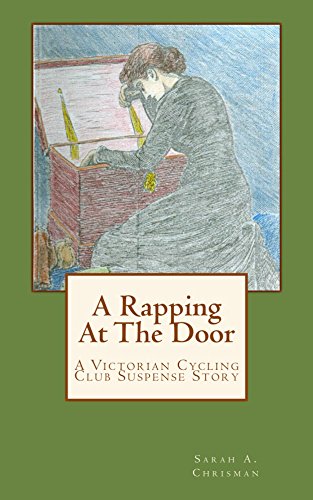

On the grounds near the big house are two buildings which made our mouths water: one of the biggest smokehouses in Tennessee (made of red brick), and a charming little stone dairy built in 1884. Of course, one could certainly not overlook the carriage house. Speaking there was an experience we'll never forget, and we were immensely flattered to meet all the wonderful people who came to hear us. One couple travelled all the way from St. Louis! After our talk I signed copies of my books, and it was sweet to see how excited people were to read my work.

[1] The Daily American, Nashville, Tennessee, October 17, 1887.

[2] The Daily American, Nashville, Tennessee, October 17, 1887.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed