|

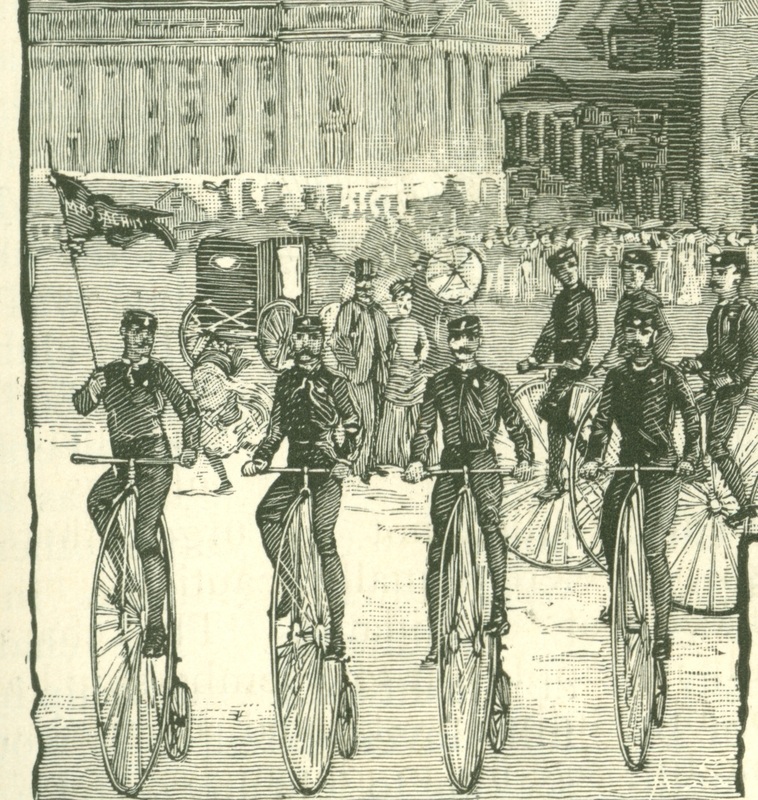

Some photos of my first ride around town on my tricycle! For more information about this marvelous machine, please see our cycling page! Holding up Gabriel's Ordinary so he can take the picture!

Here's an interesting little bit of trivia some of you may not know: King County (the county which contains Seattle, and also my hometown of Renton, WA) was originally named after William Rufus de Vane King (a U.S senator and slave owner) in 1852. In 1986, King County was "re-named"—er—King County, this time after Dr. Martin Luther King, human rights advocate. To read more, go to: http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm…

While doing research for a book on cycling (past and present) I came across this passage in an 1883 bicycle magazine, The Wheelman. It reminded me of my old algebra teacher back in high school. Enjoy!

"One of the problems given to lady candidates for civil-service appointments in a late examination was as follows: "A starts to walk from one town to another at the average rate of three miles an hour; forty minutes later a bicyclist (B) starts on the same journey at the rate of twelve miles an hour. On reaching the second town B rests half an hour, and, after riding forty minutes on his return journey, meets A still on his way. Find the distance between the two towns."" —"Wheel News." The Wheelman. June, 1883, p. 234. Hi everyone! I received a very nice e-mail from Ann Grogan of Romantasy Corsets: She asked me to help let people know about a raffle she's holding to help raise money for a battered woman's shelter in San Francisco—the details are here on their home page: http://www.romantasyweb.com/Merchant2/merchant.mv

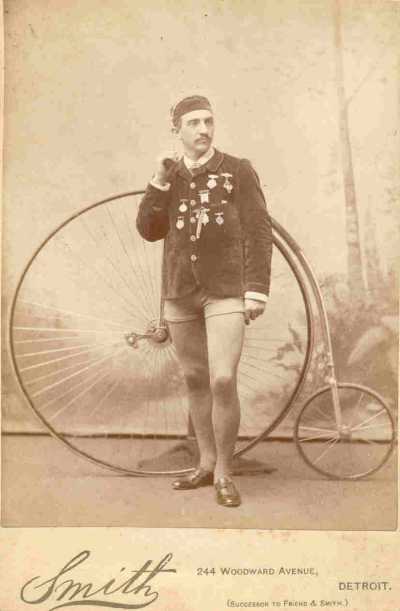

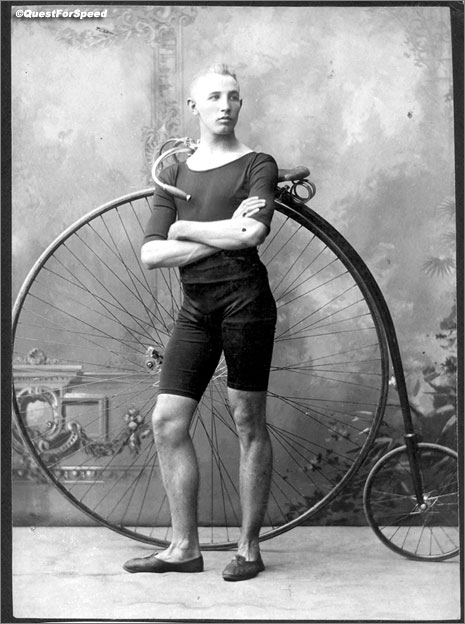

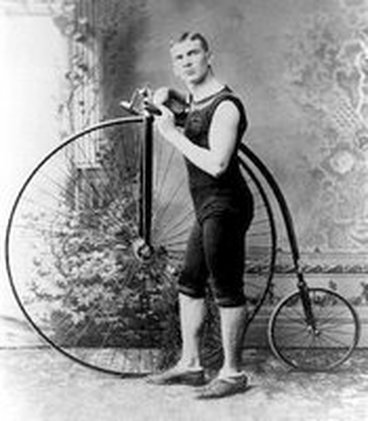

Check it out and pass the word along; it's a good cause and you might win a corset! The following is from an 1883 article in the cycling magazine The Wheelman. Its statements about human motivations are still strikingly pertinent—I wish cyclists still had the clout now that they did at the end of the nineteenth-century! "...The idea struck Mr. Green that it would be a popular thing with his constituents, especially with those who drive horses, to use his influence in the Legislature to deprive these bicycle-riders of their lawful rights upon the highways. He considered them only a few boys, or wild young fellows, of no political account, whose rights it would be safe to extinguish, and that so doing would win popularity and votes for himself. Then would that class of horse-owners, who imagine that the public highways were constructed for their especial benefit, and that all others are permitted to use them only upon sufferance, rise up and call him blessed, and vote for him next time. This is not, perhaps, exactly the language in which Mr. Green thought it out, but this is the real substance of his ideas. And probably other legislatures entertained these same ideas. But the Ohio state branch of the L.A.W. [League of American Wheelmen] was aroused. It made known the case to the L.A.W., and that great organization was aroused. All the clubs in the State were aroused. Some of them obtained an expression through the public press. Others made known their opinions to members of the Legislature. The L.A.W. spoke through its organs. The members of the Order demanded a hearing before the legislative committee, having discovered that it had something greater to deal with than a few boys, or wild young men, of no political account, accorded a hearing to the representatives of the L.A.W. That hearing was accorded, and the L.A.W. representatives were listened to with respectful consideration, largely because they represented a powerful organization, possessing control of money, brains, business and social influence, votes and representing an unknown but evidently considerable political power. A few boys, of no political account, would have been accorded no such respectful hearing, notwithstanding the fact that the rights of a few boys, or of one boy, was of just as much moral importance as the rights of any number of citizens. But everybody knows that it makes a vast deal of difference, practically, how many votes a pleader before a Legislature can control if wronged. ... Mr. Green, and probably others of the Legislature, cannot easily perceive the truth that the public highways are maintained for the use of the whole public, and not merely for the use of those who own horses. Bicyclers dismount and put themselves to much trouble to avoid frightening horses, but they do this because they are gentlemen, and from courtesy only. They are under no legal and no moral obligation to do so. Every man who drives a horse runs his own risk, if he goes upon the highway with a skittish, half-broken, badly-trained animal. In the ultimate view of both the law and common sense, man has the primary right upon the highway, and all animals of burden must yield, if there is occasion for yielding, to man. The pedestrian first, the man on any vehicle propelled by himself next, beasts afterward. This is the fundamental principle, which is as ancient as the body of the law. B has as much right to drive an elephant, a camel, or an ass, or ox, as A has to drive a horse. If A's horse is frightened by B's elephant, camel, ass, or ox, B is under no obligation to stop, or to give A's horse any more than half the road. If A drives a horse which is so untrained that it gets frightened at any of B's lawful acts, A runs his own risk, and must not only bear any damage which he suffers himself because of the whims of his horse, but he is also liable for any damage which his unruly horse may do. For instance, A's horse is frightened by the passing of a railway train, and runs into and break's C's carriage. It has been again and again adjudged that A not only must bear his own loss, but must also pay for the damage his horse has done to C's carriage. Again; D has a right to carry an umbrella on the highway, no matter how much A's horse objects; and E may push a handcart, and F draw a baby-carriage, and G march a brass band, playing, down the road, and H haul a clattering threshing-machine; and so on to the end of the alphabet, and A and his horse must take care of themselves as best as they can. Now, of all the various objects which horses sometimes shy at, a bicycle is the quietest, the least alarming, the least obstructive and dangerous, and horses become accustomed to it soonest and easiest. Indeed, the great majority of horses do not shy at it even the first time they see it. But, while these are the abstract rights of the case, it is plain that these rights, or any rights, are secure, largely because of the political power of bicycle-riders... Let us, by all means, keep the L.A.W. and all its branches and clubs entirely aloof from politics in the ordinary sense; but let us, whenever our just rights are assailed through politics or politicians, be ever ready as an organization to wield our political power, strongly and efficiently in self-defence. The fact that we possess political power is our shield; the fact that we are ready to use it when attacked will double the strength of our shield. We trespass upon the rights of no man; let us make it plainly understood that no man will be permitted to trespass upon our rights with impunity." -President Bates of the L.A.W. "The Political Power of the L.A.W." The Wheelman. May, 1883, pp. 98-100. While researching photos from the 1880s, I came across this rather astonishing picture on the Wheelman's website: http://www.thewheelmen.org/sections/photographs/highwheel/regviews/highwheel1v.jpg Sportswear did tend to be shorter than regular clothes, but this gentleman seems to be taking the matter to extremes. He appears to have put his uniform jacket over a racing singlet for the photo, but he's showing a lot of leg even by racing standards. (Admit it: He's showing a lot of leg even by modern racing standards!) For comparison, here are some other racing outfits of the time: I always love it when history makes me re-evaluate something I thought I knew—in this case, just how short someone was willing to wear their garments in the 1880s. It's a wonderful reminder that diversity of choice exists in every era. A description of the company which produced Gabriel's 1887 Singer Challenge Ordinary bicycle, written in the year they made it! "A visit to the works of Messrs. George Singer & Co., of Coventry, will at once give a stranger an idea of the extent of the cycling trade. Established in 1875, Messrs. Singer & Co. did not make any specialty of racing machines until the season of 1885, having devoted their attention almost entirely to turning out all classes of road machines, bicycles, tricycles, manumotive velocipedes, children's velocipedes, and in short every description, the number of patterns being remarkable. The works in Alma Street are excellently arranged. Entering through a large hall, partly occupied by a clerks' office through want of more accomodation, the visitor passes into the large shop, on either side of which are to be seen storerooms containing an apparently inexhaustible supply of parts and fittings, piles of castings, bundles of steel tubing, coils of wire, lengths of iron material, indiarubber [sic] tires, all stacked ready for use; whilst in every room not otherwise used may be seen, in the spring of the year, hundreds of completed machines packed as closely as they will go, ready to be dispatched from the great packing-room across the road—which is the old Coventry Rink—now converted into a cycle shop, where machines of all classes are daily being packed and dispatched to every part of the globe. In the main shop, all the operations for the production of the various machines are to be seen going on with steady activity. Here is a workman drilling holes in a hub with the aid of a machine which not only drills them at the proper angle, but spaces them as well. Another is running the thread of the screw on to the spoke. Yet another is heading them. And all these varied operations go on continuously and without intermission throughout the year. For during the dead season Messrs. Singer work hard to lay up the stock which is to be seen in the store-rooms early in the spring. The Premier Works are also extensive and very interesting... There are a large number of other firms engaged in the production of specialties, and so extensive is the industry that the production of minor parts and castings for the trade finds employment for large firms and much capital. Thus Messrs. John Harrington & Co., of Coventry, are devoted to the production of the well-known Arab cradle spring, and to the enamelling process which has now been adopted by a large number of manufacturers; Messrs. Thomas Smith & Sons, of Saltley Mill, Birmingham, supply the trade with castings and finished parts to almost any extent; Mr. W. Bown's ball-bearings have won an excellent name for themselves, and are largely adopted by the manufacturers; Messrs. Lamplugh & Brown, of Birmingham, the cyclists' saddlers, supply the trade with saddle-bags and other leather goods, requisites which have done a great deal to make riding comfortable; and a number of other instances could be given to show how great is the general demand in connexion with the cycling trade."[1] [1] Bury, Viscount. and G. Lacy Hillier. The Badminton Library of Sports and Pastimes: Volume I: Cycling. Ed. The Duke of Beaufort, K.G. and Alfred E.T. Watson. London: Spottiswoode and Co., 1887, pp. 65-67. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories |

***

RSS Feed

RSS Feed