"...The idea struck Mr. Green that it would be a popular thing with his constituents, especially with those who drive horses, to use his influence in the Legislature to deprive these bicycle-riders of their lawful rights upon the highways. He considered them only a few boys, or wild young fellows, of no political account, whose rights it would be safe to extinguish, and that so doing would win popularity and votes for himself. Then would that class of horse-owners, who imagine that the public highways were constructed for their especial benefit, and that all others are permitted to use them only upon sufferance, rise up and call him blessed, and vote for him next time. This is not, perhaps, exactly the language in which Mr. Green thought it out, but this is the real substance of his ideas. And probably other legislatures entertained these same ideas.

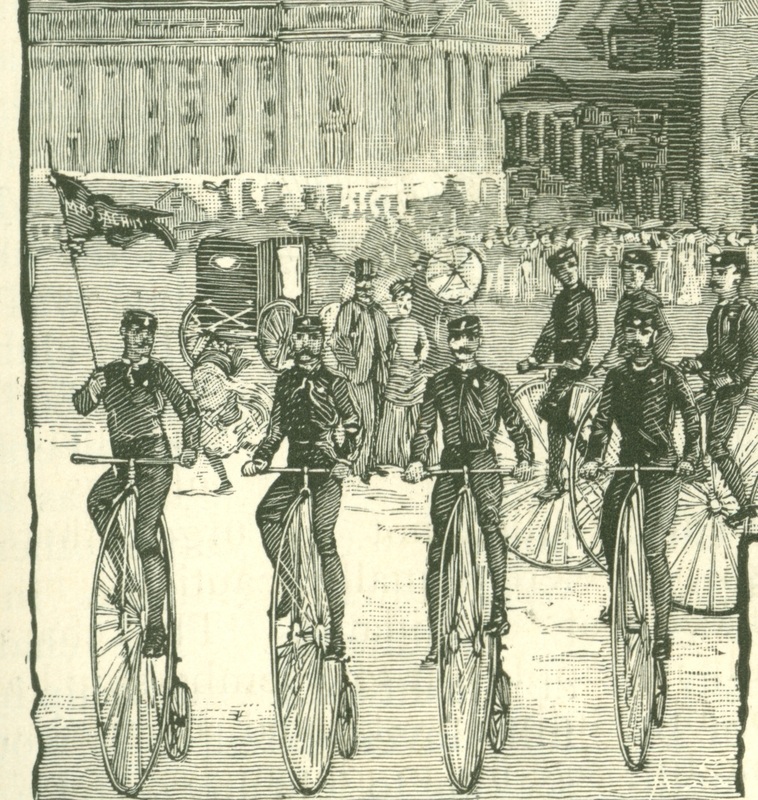

But the Ohio state branch of the L.A.W. [League of American Wheelmen] was aroused. It made known the case to the L.A.W., and that great organization was aroused. All the clubs in the State were aroused. Some of them obtained an expression through the public press. Others made known their opinions to members of the Legislature. The L.A.W. spoke through its organs. The members of the Order demanded a hearing before the legislative committee, having discovered that it had something greater to deal with than a few boys, or wild young men, of no political account, accorded a hearing to the representatives of the L.A.W. That hearing was accorded, and the L.A.W. representatives were listened to with respectful consideration, largely because they represented a powerful organization, possessing control of money, brains, business and social influence, votes and representing an unknown but evidently considerable political power. A few boys, of no political account, would have been accorded no such respectful hearing, notwithstanding the fact that the rights of a few boys, or of one boy, was of just as much moral importance as the rights of any number of citizens. But everybody knows that it makes a vast deal of difference, practically, how many votes a pleader before a Legislature can control if wronged.

... Mr. Green, and probably others of the Legislature, cannot easily perceive the truth that the public highways are maintained for the use of the whole public, and not merely for the use of those who own horses. Bicyclers dismount and put themselves to much trouble to avoid frightening horses, but they do this because they are gentlemen, and from courtesy only. They are under no legal and no moral obligation to do so. Every man who drives a horse runs his own risk, if he goes upon the highway with a skittish, half-broken, badly-trained animal. In the ultimate view of both the law and common sense, man has the primary right upon the highway, and all animals of burden must yield, if there is occasion for yielding, to man. The pedestrian first, the man on any vehicle propelled by himself next, beasts afterward. This is the fundamental principle, which is as ancient as the body of the law. B has as much right to drive an elephant, a camel, or an ass, or ox, as A has to drive a horse. If A's horse is frightened by B's elephant, camel, ass, or ox, B is under no obligation to stop, or to give A's horse any more than half the road. If A drives a horse which is so untrained that it gets frightened at any of B's lawful acts, A runs his own risk, and must not only bear any damage which he suffers himself because of the whims of his horse, but he is also liable for any damage which his unruly horse may do. For instance, A's horse is frightened by the passing of a railway train, and runs into and break's C's carriage. It has been again and again adjudged that A not only must bear his own loss, but must also pay for the damage his horse has done to C's carriage. Again; D has a right to carry an umbrella on the highway, no matter how much A's horse objects; and E may push a handcart, and F draw a baby-carriage, and G march a brass band, playing, down the road, and H haul a clattering threshing-machine; and so on to the end of the alphabet, and A and his horse must take care of themselves as best as they can. Now, of all the various objects which horses sometimes shy at, a bicycle is the quietest, the least alarming, the least obstructive and dangerous, and horses become accustomed to it soonest and easiest. Indeed, the great majority of horses do not shy at it even the first time they see it.

But, while these are the abstract rights of the case, it is plain that these rights, or any rights, are secure, largely because of the political power of bicycle-riders... Let us, by all means, keep the L.A.W. and all its branches and clubs entirely aloof from politics in the ordinary sense; but let us, whenever our just rights are assailed through politics or politicians, be ever ready as an organization to wield our political power, strongly and efficiently in self-defence. The fact that we possess political power is our shield; the fact that we are ready to use it when attacked will double the strength of our shield. We trespass upon the rights of no man; let us make it plainly understood that no man will be permitted to trespass upon our rights with impunity."

-President Bates of the L.A.W. "The Political Power of the L.A.W." The Wheelman. May, 1883, pp. 98-100.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed