Historical article

A MIDWINTER-NIGHT'S DREAM.

By George E. Blackham

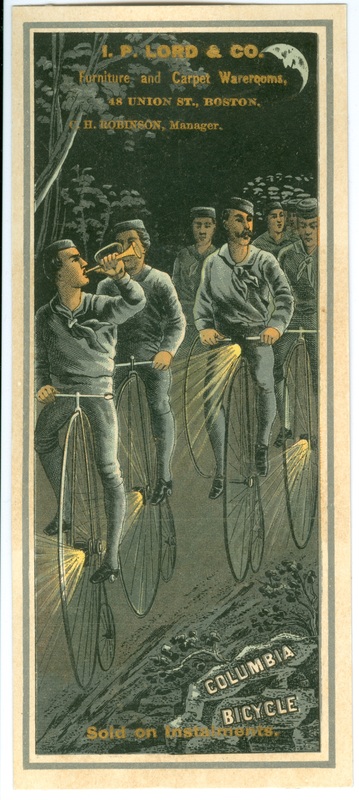

The Wheelman, April, 1883, pp. 13-15.

It was a January storm; all day long the snow had been falling in great fleecy flakes, silently, swiftly, and steadily covering roads, trees, and houses in a garment of ghostly white, and night had closed in, dark, sombre, and starless, and the mercury had fallen, and the wind had risen and came howling fierce, eager, and biting, direct from the great Manitoba storm-centre, in the far North-west.

I was weary with my day's work, and, divesting myself of overshoes, overcoat and undercoat, was soon snugly ensconced in my favorite corner, and feeling luxuriously lazy in my loose dressing-gown and slippers. The wind roared dismally without, but every fresh blast but urged the fire inside to a merrier glow. I lit my lamp, filled my pipe, and, elevating my slippered feet upon a foot-rest, proceeded to toast my toes and to fill my mind with wisdom from a heavy volume taken from my library-shelf for that purpose. I had read but a page or two when, somehow, I seemed to lose track of the argument, the anatomical details got strangely mixed, and, finally, I nodded and nearly dropped my book. I gave up the struggle, set my book aside, turned down my lamp, and sat looking into the coals through the blue veil of incense rising from the brown bowl of my meerschaum.

It was a pleasant scene,—the dimly-lit room, the familiar volumes ranged on shelves beside me, my microscope under its bell-glass, and in the corner my bicycle, —all strangely transformed by the magic of the firelight.

My dear old wheel, that had carried me so many miles with speed and safety, seemed to wink and nod confidentially at me as the flickering flames were reflected from its nickelled head and gold-striped forks. It seemed to have a reproachful look about it, and I felt guilty; for I had been planning to sell it, that I might come out with a brand-new mount of the very latest pattern in the spring.

After a few moments I was astonished to see it move from its corner and approach me, and, touching me on the shoulder with its handle-bar, whisper in clear, bell-like tones, "Mount, mount! I have much to show you."

I was loath to leave my pleasant fireside; but, impelled by some unknown yet irresistible force, I placed my foot upon the step and slid into the saddle.

In an instant the firelight faded away, the wind ceased to howl, and I found myself in the midst of a beautiful park, on the summit of a little hill, from which fine macadamized roads led north, south, east, and west. Beside me stood two figures, —one a chubby little fellow in a blue bicycle suit; the other a tall, slim chap in citizen's dress. Each led a bicycle, —the little man a lovely little machine of English make, resplendent with the glory of full nickel, and brand-new; the other a clumsy roadster, two sizes too large for him. "See," said the little man, "it is easy enough —'this way,'" and, putting a foot upon the step of his machine, slid into the saddle and circled round as gracefully and, apparently, as easily as the swallows which were chasing the gnats in the evening air. Dismounting, he laid his machine down and straddled the big one, while the long man struggled awkwardly into the saddle. "Now, then, hold her steady, and press your feet upon the pedals as they go down; the grade is in your favor. Facile descensus, you know"; and he started the awkward pair down the gentle slope.

I was smiling to myself at the figure they cut as they wobbled uncertainly from side to side, and the long man gripped the handles as if he wanted to pull them off, and kicked visciously at the pedals. "Funny, isn't it?" said the bell-like voice; "but don't you recognize the parties?" and I suddenly became aware that I was looking at myself, taking my first road ride with the kind assistance of Dr. A.--

In a moment the scene had faded, and I stood in my own door-way. The summer sun shone brightly, and a soft breeze brought perfume from the garden and dust from the street. The expressman drove up and unloaded a queer-looking crate, and drove off, while I could hardly spare time to draw the nails properly, so eager was I to get at my new wheel. "Ah! I was young then," sighed the bell-like voice, "and you thought me passing fair." So I did; and surely there was reason. Light and graceful in outline, yet strong and rigid, the new wheel stood before me; its head, pedals, cranks, and spring bright with nickel, all other parts black as night, save where graceful stripes of gold-leaf relieved the sombreness of forks and back-bone.

I was crazy to try my new steed, and was soon upon the road, revelling for the first time in the delights of ball-bearings, long handle-bar, etc., etc.

Again the scene faded, and I found myself on a well-known highway, in company with a fellow-disciple of Aesculapius. The harvest moon shone bright above us, rendering our path as bright as day, but clothing the distances in a vague veil, that half revealed, half concealed, and wholly embraced, their beauties. On our left the hills rose majestically toward the cloudless heavens, and on our right the blue waters of Lake Erie melted into the sky so imperceptibly that no man could say where the horizon lay, or draw the dividing line between

"The steadfast heavens above us

And the molten heavens below."

And the molten heavens below."

We rode swiftly on without speaking, till the silence, broken only by the chirping of the crickets, and the thousand-and-one voices of the night that seem merely silence made audible, became oppressive. I turned to speak to my companion; but, at the first word, the scene faded, and I was again in my study; the knee-breeches and long stockings were gone, the moon was hid, the winter wind howled dolefully, and my slippered feet toasted cheerfully in the glow that radiated from the sea-coal fire.

"I have shown you the past," said the bell voice. "Are you still resolved to part with me? Ah, I see you are! Well, then, mount, mount, for I must show you the future." I was again in the saddle, and it was again a summer night, but not moonlight. A hearty old fellow, with a flowing beard just tinged with gray, shot past me upon a glittering wheel. He had a companion with him, mounted like himself, and they were chatting merrily.

I seemed to keep alongside of them without special effort, though their speed was more than twenty miles per hour. "Do you remember," said the older man, whom I now saw to be myself, — "do you remmeber, doctor, the first time we rode this way together? We had to take advantage of the full moon for night-riding then, for this was not invented": and he touched a knowb on the top of his handle-bar, and instantly the whole machine glowed with the peculiar luminosity of the incandescent electric light. "Ten miles an hour was good speed in those days, before the invention of the automatic multiplying gear; and indeed, it was good speed, considering that our wheels weighed from thirty-five to fifty pounds; but that was before the days of aluminum and ten-pound roadsters. Well well, we were youngsters then, and I sometimes think we enjoyed the rude appliances of those early days better than our improved machines of today.

I was anxious to inquire of my other self more of the details of construction of his luminous ten-pound bicycle and its automatic multiplying gear; but the moment I spoke the spell was broken, and the scene changed again. I seemed to be in the same place, and yet it was not the same. The country road was a country road no longer. The low farm-houses and plethoric red barns had given place to elegant residences, with well-kept lawns; the old highway was covered with asphalt, and before me were two old gray-bearded men, mounted on tricycles, which they simply guided, while tiny electric engines furnished the motive power.

"Ah, doctor," said one of the poor old chaps, "there are great changes since we first pushed our wheels over this road, and great improvements; but, after all, I'd give all these self-moving tricycles, electric engines, and self-luminous wheels for one hour of the youthful spirit, strength, and vim with which we pushed our heavy old Columbias through the dust that summer evening thirty years ago. Machinery can never replace youth and health; and, on the whole, we have lost more than we gained in taking away the necessity for personal effort in 'cycling."

"Do you hear that?" said the bell voice; "that's what you are coming to if you don't realize in time that success in 'cycling depends far more upon the rider than the wheel."

"But," said I, "don't you see that your line of argument would put a stop to all improvement? Let me tell you—" but here the thread of my discourse was broken by another voice saying, "And let me tell you it's time you were in bed instead of snoozing here in your chair and talking in your sleep, as you have been doing for the past half-hour."

Ah, me! it was a rude awakening to the realities of existence; but I do wish I had found out about how that bicycle was made self-luminous, and what were the details of the automatic multiplying gear that made twenty miles per hour a moderate road gait.

Books make great gifts, and they're always the perfect size.

When you buy my books for someone, you're not just giving them a gift, you're also giving me the best gift you possibly can —the ability to make a living doing what I've always wanted to do. Thank you so much!

In a seaport town in the late 19th-century Pacific Northwest, a group of friends find themselves drawn together —by chance, by love, and by the marvelous changes their world is undergoing. In the process, they learn that the family we choose can be just as important as the ones we're born into. Join their adventures in

The Tales of Chetzemoka

Tales of Chetzemoka merchandise

"A minute's reading provokes a day's thinking…"

Products inspired by the Tales of Chetzemoka series, books beloved by fans young and old around the world.

A Christmas Wish

Victorian Winter Poetry for Christmas and New Year's

"Had I power to give to you

Many a rich and costly gem,

Fit, in brilliancy of hue,

To adorn a diadem,

I'd bestow the jewels rare

On some other friend less dear,

While for you I'd breathe a prayer,

Such as I do offer here.

Many a merry Christmas, friend,

Health, contentment, joy and bliss;

More delights in thought I send

Than I can convey in this.

With the now departing year

May your cares and sorrows cease;

May the new one, drawing near,

Bring you happiness and peace." —1883

As soon as winter arrives, when icy pictures appear on windows and Jack Frost makes maidens blush, our thoughts turn to Christmas. Treats are baked, larders filled, and hunts for mistletoe lead to the most delightful results. Children eagerly await Santa Claus and older folks fill their stockings with memories old and new. Finally the day comes with all its joys and celebrations, and even then we still have more to look forward to, for there is still New Year's to come with all its hopes and promises. This delightful collection of Victorian poetry is perfect for cozy winter evenings. Cuddle up by a crackling fire while the snow flurries outside and share these delightful old verses with all your holiday guests, young and old. Compiled and edited by Sarah A. Chrisman, author of the charming Tales of Chetzemoka series as well as This Victorian Life, Victorian Secrets, and others.

On Amazon

***

Our cycling page

Cycling images

Cycling articles:

A Burglar, A Bicycle, and A Storm (Fiction—1896)

A Cycle of the Seasons: A Bicycle Romance in Four Meets (Fiction—1883)

A Cycle Show in Little (1896)

A Header (?) (Poem—1883)

A Modern Love Sung in Ancient Fashion (Poem—1884)

Bicycle Riding In The United States (1881)

Bicycling and Tricycling (1884)

Bikes on Trains (1883)

Cycling's Value As An Exercise (1879)

Cycling for Women (1888)

Is Bicycling Harmful? (1896)

An Early Morning Ride (Poem—1883)

The Evolution of a Sport (1896)

Foreign [Bicycling News] (1884)

My Wheel (Poem —1883)

'Neath the Magnolias (Poem—1883)

On Wings of Love (Poem—1884)

Rosalind A Wheel (Fiction—1896)

Snakes in his Wheel (1895)

Wheelman's Song (Poem—1883)

The Work of Wheelmen for Better Roads (1896)

Woman's Cycle (1896)

Christmas pieces:

The American Carver (Poem—1887)

Winter Cheer (Poem—1888)

A Christmas Glee (Poem—1890)

A Pine-Cone Christmas (1890)

Christmas Pensees (Poem—1890)

Santa Claus in Our Village (1889)

***

For words of wit and advice sage,

I hope you'll like my author page!

History lessons, folks who dare,

Please do share it while you're there!

https://www.facebook.com/ThisVictorianLife

Thank you!

Search this website:

***