Historical article

A PINE-CONE CHRISTMAS

By Mary E. Child

Good Housekeeping, December 6, 1890, pp. 263-267.

"I wish," said Benny, wistfully, "that I had something to do."

But none of the family seemed to heed the remark. Farmer Stebbins scowled before him and brooded over the mortgage. His overworked wife sighed and kept on with her mending. The children did not look up from their studies, and Jake, the hired man, dozed in a corner. Miss Stain heard the pathetic words and smiled into Benny's eyes sympathetically. She did not wonder that he was lonely and tired of sitting in that cheerless room, reading the weekly paper over and over, or the few books that he already knew by heart. She herself felt like throwing out her arms as Benny had, and protesting against the emptiness of the Stebbins's life.

Miss Stain taught in the village school and boarded with the Stebbinses. Every day Jake took her and the children to the little red school-house in the village, and came for them at night. After school hours she taught Benny. Benny was a cripple—a hunchback. She was very fond of Benny.

Miss Stain looked about the room, mentallly debating whether she should go upstairs and sit the evening through alone, or remain with the silent family. Either was bad enough. Perhaps it was because there should have been a Christmas bustle in the air; that there should have been delightful mystery depicted on the mother's face; that Georgie and Bess should have been on tip-toe with excitement and curiosity, that the absense of these made her notice, as never before, the cheerlessness of the living-room, and remember that outside the fields were white with snow, that the orchard trees were leafless, and that for miles up and down the country road not a living creature could be seen.

By and by Benny slipped from his chair and went over and stood by his father. How small and pale he looked—that crippled boy—beside the muscular, weather-beaten man!

"Pa," he said, coaxingly; he laid a wasted hand on the shabby sleeve, and looked wistfully into his father's face; "don't you think—that mebbe—we could have a Christmas this year? An' a tree? We never had a tree."

The children raised their heads from their books and listened breathlessly for the answer. The mother held her needle supended in the air, anxiously. Miss Stain waited, hopefully, and Benny clutched more tightly at the sleeve, while his eyes grew big and bright.

The children did not know that a lump came into the father's throat and a mist into his eyes at the sight of the pinched face and at the touch of the little hand. It was a pity they did not know that he would have given his farm, at that moment, to have been able to say, "Ah, that we will, my boy!" But the mortgage raised its ugly head. It was always thrusting itself upon them. They were so tired of thinking of it, of hearing of it! If it would only go away at Christmas time! But it did not go away; it was there, and they could not forget.

"Christmas!" cried the farmer, bitterly. "What's Christmas to us? Christmas is for rich folks, not poor ones. There won't be a Christmas here, I'm thinkin', till Christmas-trees grow their own presents!"

Benny slipped into his chair again, without a word, while the other children winked back the tears and tried to swallow the lump in their throats that hurt so. They had learned the uselessness of entreaty. The mother sighed and plied her needle once more, and Miss Stain decided to go upstairs.

What a pity! she thought over nad over when she was in her unattractive room. What a pity! to be a child and not expect a Christmas! To be young, and not look forward with the certainty of Santa's coming to the Best of Days! The teacher forgot her homesickness; forgot that she was not going to spend the holidays at Annis, as she had planned; forgot that she was far from home and kindred; forgot everything but the hurt, patient look in Benny's eyes, and the grief in the other childish faces.

If only her salary were not so small! If only she could think of some plan of a Christmas for those four children! After she was in bed, she lay awake for a long time, thinking, fancying the wind rushed by shrieking, in a hurry to pass a house where there would be no Santa Claus. Oh, if the spirit of Christmas could but once cast his genial spell over the household! She fell asleep, still thinking of the children, and dreamed that Santa Claus was in the top of the old pine-tree in the yard, pelting her with cones, and that as they touched her hands, they turned into beautiful Christmas presents.

The next morning, as Miss Stain stood waiting outside the door for Jake to drive up from the barn, she noticed that the wind had shaken dozens of cones from the pine-tree. Just why she stooped and picked one up, she could never tell. It must have been the spirit of Christmas that made her examine closely the brown, scaly thing. As she looked, a sudden thought came to her like an inspiration. Why could not something be made of those delicately cut, shining scales? She had been termed ingenious, and had the knack of making pretty things out of little. Why could she not bring her ingenuity to account, when so sorely needed? She thought of it all the way to the school-house, looking at the cone again and again, sure that there were great possibilities in those brown scales. I am afraid that for the first time in her experience the conscientious little teacher allowed thoughts other than of lessons to enter her mind that day, for certain it is that when she came home at night, she was full of a plan that she had developed, and so animated with enthusiasm that unconsciously she brought a cheery little gleam of sunshine into the dreary home circle.

Miss Stain found Farmer Stebbins alone in the living-room, gazing moodily out of the window. She was somewhat afraid of him; he had adverse opinions regarding so "much schoolin'." He believed that "this learnin' put a lot of tom-foolery into the young ones' heads an' made 'em want things they couldn't have." And he had a way of speaking crossly. Miss Stain dreaded unfolding her plans to him, but it must be done, and there was no time to be lost.

"Mr. Stebbins," she said, "I've thought of a plan to-day that I think would please the children. You know I'm fond of the children, especially Benny."

Ah, yes, Benny! It may be the father remembered that a time might come when there would be no Benny, when only the crutch and the low chair and the few worn books and the memory would be left. At any rate he turned from the window and let her tell her plan, without so much as an impatient interruption. He did not seem to be much impressed by it. He had never heard of a Christmas that cost nothing, he said. But if she wanted to try, well and good, only she must remember he'd no money to throw away. He was not very enthusiastic, certainly, but the young teacher was not discouraged; on the contrary, she was even jubilant, and Benny coming in just then, she hugged him in her delight.

"Oh, Benny! we are to have a Christmas! Your father says so."

"Did you, pa?" Benny could not credit his ears.

"It's the teacher's doin's; I haint a hand in it. I don't take much stock in it myself, but she can try, long's it don't cost nothin'."

After supper, Miss Stain and Mrs. Stebbins had a long talk out in the kitchen. No one paid attention to it, save Benny, who was full of the importance of the secret he was carrying. But when teacher opened the door a bit and called to Benny and Susie to come out there, Georgie and Bess began to wonder what was happening. Jake called it a "pow-wow." What was a "pow-wow"? Was it fun? Was it as good as Christmas? Was it a Christmas? The idea was too good to consider even. But what made Benny cry, "Oh, Teacher!" and Susie exclaim, "How perfectly lovely!" Something was going to happen. It must be—they dared not say it, but in their little hearts they hoped it—a Christmas!

For this is one of the dearest things about dear old Santa. He knows the pleasure of anticipation, and the very minute he is reasonably sure his overtures will be received, he establishes a sort of telegraphic communication between each little childish heart and his great Christmas office. Those Christmas mysteries—the knowledge that sister slips something out of sight when you come in, and that mother starts, quite flustrated, when you appear suddenly; all the little smiles and sly glances and knowing looks—don't you suppose that Santa sends them on purpose to let you know?

So the children began to suspect, especially when they heard their mother rummaging around in bureau drawers and chests and even in the attic. When Susie and Benny staid [sic] all the evening in Teacher's room and would not let them so much as peep in, they were more than certain that something "Christmassy" was brewing.

Miss Stain was not long in getting her materials together and her workers started. There were but two weeks before Christmas, and not a moment to be lost. The day after Mr. Stebbins had given his consent to the plan, before Jake came to take them home, she slipped over to the establishmebnt known in the village as the Store, where everything in the way of general merchandise could be obtained.

She wanted boxes—"any kind, size, shape or color"—she smilingly told Mr. Dick, and that individual, glad to get rid of them, set out a quantity upon the counter. The number that Teacher selected surprised the group of village idlers gathered around the stove into something like animation. She was laying aside boxes, big and little, square deep boxes, large flat boxes, long narrow boxes, shoe boxes, hat boxes—why, it did seem as if Teacher had gone crazy over boxes; what was she going to do with so many? Mr. Dick could scarcely restrain his curiosity, and the loungers could not remember when they ever before had been so "stirred up" by anything!

After selecting as many as she wished, Miss Stain asked for the little wooden boxes such as berries come in, and for peach and grape baskets. There were not so many of these, but Mr. Dick managed to find several, some in use as receptacles for various articles in the grocery line, which he obligingly emptied, insisting he did not need them. They were all somewhat dilapidated,—old, stained and dusty—but Teacher assured him it made no difference, and that Jake would call for them all in the morning. Then she bought a spool of brown thread, ten cents' worth of linseed oil, a bolt each of the narrowest satin ribbon in red, yellow and blue; a small bottle of gold paint, and a few sheets of different colored tissue paper, and departed, leaving Mr. Dick more mystified than ever.

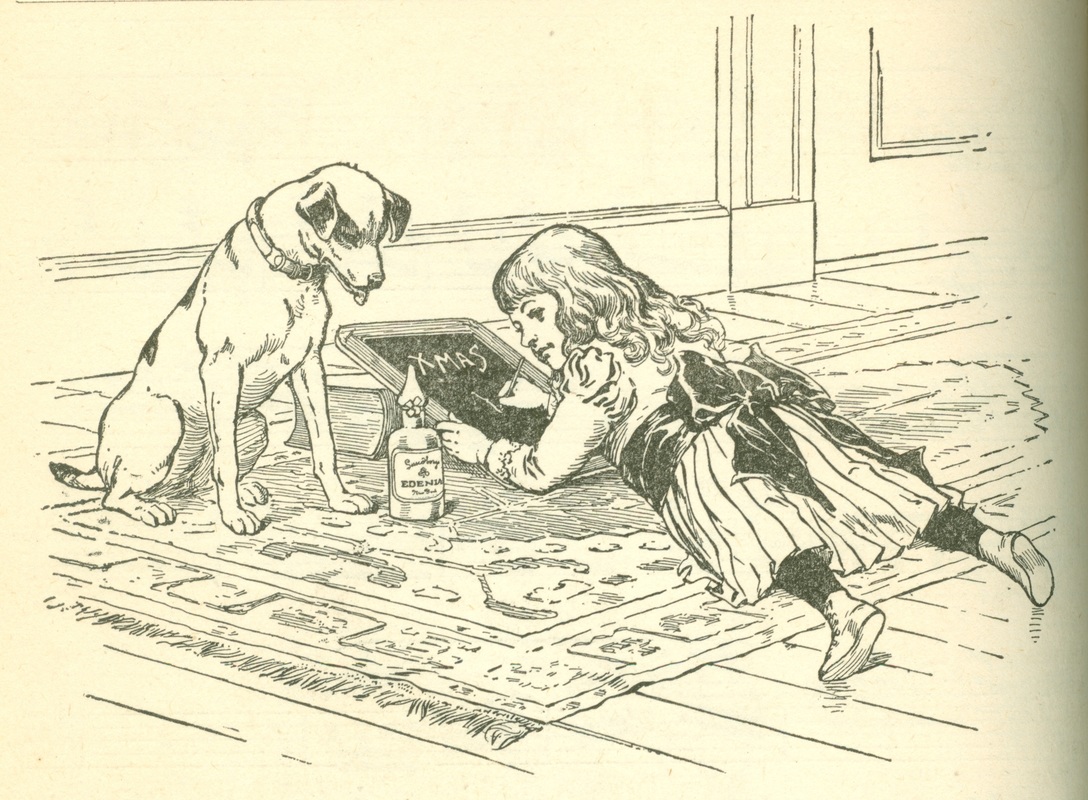

Meanwhile Benny, at home, had been hard at work. His mother had gathered a quantity of cones, and had found a great many in different parts of the house that the children had brought in from time to time. Some had fallen in early summer and were a beautiful green, some were golden, and the greater number the brown of the ripened cone. With his sharp jack-knife, Benny cut the scales from the cones, beginning at the stem end, and cutting one at a time, carefully, so as not to break or splinter it. It was hard to do this at first, but a little practice enabled him to do it easily and skillfully. He cut close to the cone-stem, that as much as possible of the red-brown tints might be left. Benny had never noticed how beautiful these tints were, nor how wonderfully the scales overlapped, each attached to the cone by a flinty, pin-like thorn, and hiding two little winged seeds.

He worked energetically all day, and when school was over and Teacher back there were piles of loose scales ready for her.

"You've cut them nice," she said approvingly. "Those green and gold will work up finely."

Yet it did not seem that anything pretty could be made from those dusty brown and green cone-scales. Benny and Susie looked dubious, but Miss Stain was in the best of spirits.

"Wait a bit," she said, producing the linseed oil. The scales were put in this in old earthern dishes and stirred about, that each might be wet. "Now we will let them lie in the oil until after supper," directed Teacher.

After the meal was over, when the dishes had been "done up," there was another "pow-wow." Georgie and Bess fairly quivered with curiosity by this time. Once or twice they discussed the feasibility of breaking into the room. They contented themselves, however, by stealing guiltily upstairs and listening at Teacher's door, but it was very quiet inside, and the cold soon drove them back to the living room, there to whisper together over the remarkable turn affairs had taken and to speculate on what the Christmas would be like.

The four in Teacher's room were too busy to talk. They sat around the little table, each with a pile of scales before him, rubbing and polishing away for dear life. The oil had softened and brightened the scales, and the rubbing cleaned them. When wiped and polished the scales were scattered over newspapers to dry. The rags they had used were burned, to prevent a farm-house bonfire, Teracher said, and the party separated for the night.

Miss Stain then took an inventotry of her stock. Mrs. Stebbins had brought her the results of her search. "'Tain't much," the poor woman had said. "I've brought everything I've got that you thought you could use; but, land sakes! what you can do with that truck beats me!"

But the teacher accepted the scanty contribution gladly, although it was, indeed, not much—a few faded ribbons, some pieces of an old brown silk dress that many years ago Mrs. Stebbins had proudly worn; some bits of a pink chambrey frock that Bess had outgrown, and a yard or so of turkey-red cotton. Miss Stain examined them thoughtfully; then she went to her closet and took down a white wool dress that hung there. What good times that dress had seen in the days that were before she had been obliged to strike out for herself and seek a livelihood! It had seen several years' service, but it had been worn carefully, and the white surah sash that was attached was not soiled, only creased. How pretty that sash was! Should she do it? Would it be a sinful waste? It could be pressed and worn a year longer. But Miss Stain remembered the children and Benny's joy at the hope of a Christmas, and hesitated no longer. She unpinned it from the dress and, taking her scissors, resolutely cut the beloved sash into three parts. It was for Benny's sake. These with a few ribbons of her own, and a somewhat worn white silk handkerchief, she laid aside with Mrs. Stebbins little offering, and went to bed.

The next morning, before it was time for school, she descended into the kitchen, taking the silk pieces, and in a trice, almost, they were dyed beautiful shades of red, yellow and blue, with diamond dyes of those colors that she had had left from dyeing silk for a rug some time before. Jake took the boxes back with him, after he had left the four at the school-house, and Mrs. Stebbins hid them in the teacher's room.

Friday evening the real work began. Teachr made the first pine-cone article alone, Susie watching and proving an apt pupil, Benny sorting the scales, keeping needles threaded and rendering assistance in various other ways. There were busy times for the next fortnight, but the last week was vacation, and much was accomplished. As one article after another was finished, Miss Stain's fertile brain suggested a new one, and her busy fingers soon achieved a fresh triumph.

Perhaps you might like to follow her example and have a Pine-Cone Christmas. Miss Stain selected one of the small berry boxes. She first covered the open space at each of the corners with a bit of silk, fulling it on to make it stand out soft and fluffy. Around the top she put a binding of silk, but sewed it on full, so that it was more of a puff. She turned the edges under at the top of the silk at the corners, but along the sides of the box, inside and out, she did not hide the raw edges. Next she sewed on the scales, beginning at the upper right-hand corner, placing the first one so that its tip lapped over and hid the edge of the puff and also the raw edge of the first, and also the raw edge of the puff at the corner. The second scale lapped a trifle over the first, and so on around the box. The second row was put on so that the tip of each scale came between the two above it, as low as possible without showing the stitches, to let the red-brown tints be seen. In her prettiest articles, Miss Stain put on a few rows of green scales, then of golden, and finished with the brown, which produced a beautiful shaded effect. She found the largest scales most satisfactory, being more showy and easily sewed on. The box covered with the scales, it was set aside and the lining prepared.

Five pieces of pasteboard, each a trifle smaller than the sides and bottom of the box, were cut out and covered with a layer of cotton batting. Next, silk was cut, larger than the pasteboard, and caught in loose soft folds to it. (In some linings afterwards she tufted the silk at regular intervals.) The silk left at the sides was turned down all around over the pasteboard and fastened. When each of the five pieces had been treated thus, they were slipped, a side at a time, into the box, and fastened securely, and the bottom pressed in the last. The cotton batting had made the pieces larger, and they thus were just the size of the box and fitted snugly. A row of the narrow satin ribbon, matching the silk used, was sewed around the bottom of the box outside to cover the stitches in the last row of scales, a bow was placed at one of the upper corners, and the dainty box was completed, repaying tenfold its trouble and expense. By the addition of a cover, "scaled" and lined as the box had been, and attached to the box by ribbon hinges, tiny bows of ribbon hiding each end of the hinge, a charming Handkerchief Case was before them.

A Glove Box was made in the same way, using a long narrow box for a foundation, and a Jewel box was also treated as the first, after having been divided into compartments by strips of pasteboard, covered with silk.

A wooden grape-box, a foot square, was converted into a beautiful receptacle for photographs, and another like it, made in the same way, was changed by the addition of pockets into a pretty Work Basket.

Miss Stain made this especially for Susie. She lined the box with pink chambrey. On three sides she sewed full pockets, and in one corner a tiny one for a thimble. The fourth side was occupied by a little emery-bag, a somewhat larger stuffed bag for pins, and a dainty needle-book made of chambrey-covered pasteboard and leaves of pinked white flannel.

A screen-shaped Photograph Frame was next considered. Six pieces of pasteboard were cut, about six inches by nine in size. An oblong hole was cut in three of them—the picture window, Benny called it. The other three were covered on one side with silk brought over so as to cover the edges. In making a second frame these backs were simply gilded, and laid, silk side down, less than half an inch apart, and each two joined together by pasting a hinge of silk about an inch wide and as long as the frame over them. The three with the "windows" were finished at the outside edge by a narrow puff and the scales sewed on, beginning at the outer edge, tips outward. The base of the scales converged at the picture space, and the stitches and edge of the board were hidden by a narrow puff. The three "scaled" pieces were then attached to their mates and each sewed firmly on three sides, after which the frame was ready for its pictures.

A Hair Receiver was made from a round of pasteboard about six inches in diameter, clipped an inch deep all around at intervals of an inch. These clipped pieces were turned up a trifle and each lapped over its neighbor sufficiently to make the pasteboard hemispherical. Three rows of scales were sewed on, finished with a puff of silk, and the remaining space gilded. The puff gave the rounded bottom a foundation and prevented its "wabbling". A piece of silk, half a yard long and six inches wide, was joined at the ends, gathered to the size of the pasteboard and sewed inside the edge. If one is skillful, it is better to sew the silk on the pasteboard first and then add the scales. The top part of the silk was then hemmed, and a ribbon run in, and a convenient little bag that would not overturn, and might be placed on the bureau or hung beside the toilet table, as desired, was the result of their labors.

A Jardiniere was made from a bandbox, the curved side made the desired circumference, and cut in two parts. When sewed together again the pieces at the bottom were made to overlap more than at the top, to give the necessary slope. Rows of scales were then sewed on. In one jardiniere they were sewed on to the bottom and the narrow ribbon used to hide the stitches; in the other the scales came a little over half-way, the uncovered part being finished by a band of wide ribbon. Jake sawed round pieces of wood the size of the bottom, and this was slipped in and fastened with tacks just before the ribbon was put on. The jardiniere was highly satisfactory, and any plant might be proud of so dainty a crock covering.

Match boxes were made in the same way, and tiny Pincushions also, with the difference that the boxes were filled with bran and a cover of silk added.

A Lamp Mat was made of a round of felt a foot in diameter. Beginning at the edge, three or four rows of scales were sewed on and finished with a puff of silk, leaving a bare space for the lamp standard. Another was made in the same way, the felt being first cut in deep points.

A Waste-Paper Basket was made from a peach basket. The spaces between the strips of wood were filled in with turkey-red cotton and the puff put on at the top. After the scales were added a lining of turkey-red was quilled in and a narrow piece bound about the bottom outside. A second Paper Basket, equally pretty, was made from an old muff-box.

The three were pretty well tired by this time, but Miss Stain had one more idea to work out, and the most unique and perhaps the most beautiful of all the articles was made. It was a Hand Bag.

She found a piece of Mrs. Stebbins's silk, which was a pretty shade of golden brown, and was good. She took two pieces, the breadth of the silk in length and about fifteen inches wide, and joined both ends. One edge she hemmed and made a place for a draw-string at least an inch from the top of the hem. The other edge she drew almost together, within, say, an inch. A round of silk was then sewed on over this space from inside, and the gathered edges of the bag were fastened smoothly to it. Next, a round piece of strong cloth, about nine inches across, was cut in the shape of a large, five-petaled daisy. Teacher drew the design first on paper by eye, and then cut the cloth by it. This "daisy" was covered with scales, beginning at the tips, and working in. When the piece was covered, the center was fastened to the center of the bag and the petals sewed down. Done neatly, the bag did not require a lining. The silk was spread as smoothly as possible underneath the petals, and the fullness thus came between the points. A ribbon was run in at the top, a bunch of graceful loops fastened at the bottom, and Miss Stain surveyed a very pretty hand-bag with pardonable pride.

"I believe there is no limit to the articles one could make with these scales," she said, running her hand through the heaps which were left. "A few ingenious people with taste and ingenuity could do wonders in the way of a Pine-Cone Festival for a church or some institution where a novel entertainment was needed. We might be thinking of something of the kind for next fall, and raise money to start a library for the school." And Miss Stain's busy imagination already saw the old school-room bedecked with green, and money pouring in from the sale of dainty pine-cone articles.

"We've enough things for all of us, two or three times over," said Susie. "I suppose Bess and Georgie would rather have some toys instead of a pine-cone box, but it's the best we can do," she sighed.

"It ain't so much what we get, said Benny, philosophically; "it's known' we're keepin' Christmas. And there's the tree, you know."

When Benny and Susie had stretched themselves and gone off to enjoy a well-earned rest, Miss Stain looked over the scraps of silk and pasteboard that were left, for she had an idea of which she wished the children to remain ignorant. She cut the pasteboard into odd shapes—triangles, hexagons, octagons, pears, hearts, diamonds, etc.,— and made boxes of them by sewing strips of pasteboard over and over, at right angles to them, forming sides. These quaint boxes she "scaled," lined some of them with silk and some with paper, pasted paper on the bottom to hide the stitches set in sewing on the sides, and then gilded it. Then, with covers for all and dainty bows of the scraps of ribbon left, the boxes were finished and smilingly hid away.

To say that Bess and Georgie were nearly beside themselves with curiosity, would be expressing it mildly. Nobody pretended to deny that there was to be "a Christmas." Everyone was in the delightful flutter which the days just preceding the holidays always bring, and even the father and Jake seemed to catch the spirit of Christmas that was in the very air.

Three days before Christmas, when Farmer Stebbins drove into Annis with a load of wheat, Miss Stain went with him. The children looked wistful, but their father could not be bothered with them, and Miss Stain, for some reason, did not seem anxious for their company.

"Sakes alive! she's had enough of 'em the last two weeks," said the mother, as they watched the two drive off, not thinking it was strange that the teacher should wish to be alone; but she did wonder what was in the bundle that Miss Stain had slipped so hurriedly under the seat, as if not wanting any one to see it. It was a big bundle, too.

About dark the two returned, Miss Stain very demure, but seeming to have difficulty in controlling the corners of her mouth. She went directly to her room, and no one noticed that presently Jake slipped in from the barn, where he had been unhitching the horses, and stole up to the top of the stairs, where Teacher stood, waiting to receive the big bundle he carried, and which did not look in the least like the one she had taken away.

At last there was only one day till Christmas. Hourly the excitement among the younger Stebbinses grew, if possible, more intense. Even Susie and Benny, who expected no surprises, began to grow nervous with eagerness.

In the morning, George and Bess were dispatched to the village on an errand, and during their absence Jake hauled up the fine old pine tree he had cut for the occasion, and under Miss Stain's directions set it up in the middle of the parlor.

And then those two took entire possession of the room, and let no one so much as poke his nose inside the door, not even Mother, who bustled about in smiling concern, wonderfully busy at something in the kitchen. Meanwhile Jake carried in great armfuls of pine boughs, and a, after running back and forth and up and down stairs had ceased, and the doors were shut, the bustle and stir and hammering and pounding and orders and assents and exclamations that were heard inside the parlor were simply maddening to the eager outsiders.

And then—Christmas morning! and with it the happy laugher and shrill cries of Merry Christmas! and the pattering of little bare feet running down to the stockings! How the children scampered down to peep into the four little hose that, at Teacher's suggestion, they had hung up the night before. And, wonder of wonders, there was something in each! —a little bag of candy, an orange and a Christmas trifle— a bit of ribbon for Susie, a game of authors for Benny, a rubber ball for Georgie, and a doll's chair for Bess, marked with a "Merry Christmas from Teacher and Jake." And underneath each little stocking was a pair of the blackest, brightest, shiniest shoes you ever laid your eyes upon! Farmer Stebbins had done this. The spirit of Christmas had been too much for him, "an' they'll need the shoes, anyway," he said, to pacify the mortgage.

In all their lives the children had never known such a day. Everything went right, all day through. When had breakfast ever tasted so good? When did the sun shine so brightly all the long happy morning? When were tasks so light and chores so quickly done?

Farmer Stebbins—you never would have known him!—and Jake both joined in the games that Teacher taught the children. They had authors. They played ball. It was great fun. Amelia Rosalinda, the rag doll, sat in her new chair and looked on approvingly. Dinner was served late—and when had there been such a dinner? When it was over they popped corn for the evening, and then, as it was nearly six o'clock and the tree was to be viewed at seven, Teacher—or was it Mother? —suggested that they dress in their best for the important event. The children hailed this proposition with delight, and even Farmer Stebbins, although protesting against "such tomfoolery," was induced to don his "other suit" and a collar.

Mrs. Stebbins appeared in her worn cashmere—and when had she looked better?—and Teacher came down in the white wool, that did nicely without the sash, with a sprig of pine stuck in it to look "Christmassy."

Jake had long before started a fire in the energetic little stove in the parlor, and Miss Stain went in to take a last look, she said. The children were just beginning to watch the clock and to think that seven would never come, when there was such a jingle of bells outside, such a laughing and trampling of snow at the steps, and such an unwonted stir and bustle, that for one moment the TREE was actually forgotten, as every one rushed to the windows to see what it meant. But Mother threw the door open wide, and cried Merry Christmas! quick as a wink, just as if she knew all the time what was going on (and between us, she did, too), and the shouts of Same to you! and Merry Christmas! again, that came back, made the fields ring.

The children's eyes were like saucers. Was it Santa Claus? No, it was Farmer Krebs and his family, and Farmer Tims and his family, and the minister and his wife and sister, and the young doctor, and ever so many young people. It was not Santa. It was a party! The overwhelming importance and intense delight caused at the thought of having a Christmas and a party at the same time were beyond anything they had ever experienced.

Susie and Benny simply gasped in astonishment, and John Stebbins stared. But, in a moment, everybody was shaking hands and crying Merry Christmas! over again, and acting as glad to see one another as if they had not met before in years. And Mother and Teacher laughed and laughed. They seemed immensely pleased over something.

As for that mortgage,—well, the way that mortgage marched itself off would have done you good! It had hardly had the face to peep in during the day, but now it went off altogether, and no one so much as gave it a thought the whole evening.

After everybody had shaken hands, and the snow was brushed off and wraps were removed, and cold ears and noses warmed, the tree had to be seen.

With much laughter and good-natured jostling and choosing of partners, they formed into a jolly procession and marched into the parlor and around the tree.

And what a parlor! and what a tree! Every one said "Oh!" and drank in great breaths of spicy fragrance, and looked at the tree and said "Oh!" again.

You never would have known the bare, gloomy parlor in that bower of Christmas green and color and light. Why, it was like fairyland, everybody said. The corners were masses of green to the ceiling. Each ugly picture was hidden in green, and green was over the tops of the doors and windows, and all over the walls, while bitter-sweet and partridge berries shone everywhere.

And the tree! Did ever any body see such a tree? It was a big one, but every branch and twig of that old pine was wound and hung and bedecked with Christmas fancies. There were tapers, —no Christmas tree in proper standing ever appears without tapers,—and there was something, yards and yards of it, red and blue and yellow, that was festooned all over the tree. The initiated saw that it was pine scales (Bless 'em!) strung side by side and dyed. There were also pine-cones gilded, suspended from the branches, and red partridge berries winking merrily, as if they could tell a thing or two!

But when it came to the fruit of that wondrous tree, every one was suspicious. There was not a word in the English language fit to express the admiration due. If the children were surprised before, they were utterly dumbfounded now. Susie and Benny stared as hard as the others, and wondered if they were not dreaming. There was candy! There were books and skates! and such a doll! --all dressed, WITH HAIR!

Just then Santa suddenly appeared. Nobody knows how he got there, but there he was. He bore a strong resemblance to Jake, and looked a little taller than we usually think of Santa's being. But maybe the good saint grows from year to year. At any rate, he proceded to unload the tree.

There was something for every one, which proves that somebody knew all the time that there was to be a party. And for the Stebbinses, besides the pine-cone gifts, there were such surprises. Susie's work-box was stocked—thread, needles, pins and even a silver thimble and in one of the pockets were a bottle of perfume and a dainty handkerchief. Benny had a set of books,—ah, you should have seen his face! and Georgie the skates and a knife with four blades, and Bess the doll and a tiny gold ring. If there ever were happier children, I'd like to see them. And Mrs. Stebbins had a pair of black kid gloves and a pretty handkerchief, and her husband a muffler.

The family were beyond words. Each looked at the other as if to say, Where did these things come from? But no one could tell them, and soon they gave themselves up to the enjoyment of their possessions, without trying to solve the mystery.

Miss Stain was fairly overwhelmed with compliments. The young doctor in particular seemed never tired of praising her ingenuity. To think she could make such beautiful things out of cone-scales, he said. Every one said the same.

"An' I helped," insisted Benny, with dignity.

When the tree and the gifts had been admired, they were called out to discuss sandwiches and coffee, with an accompaniment of cunning little cakes with pink icing, apples, popcorn, and cracked hickory nuts, which proved to be as satisfactory, in a different way, as the tree.

Games followed, good old games like Hide the Thimble and Blind Man's Buff, which seem to have gone out of fashion nowadays.

It was too bad to stop the fun and say good-by to Christmas and go away. But little eyes, even at Christmas, will not stay open all night, and finally wraps were donned, and the teams driven up from the barn, and, full of the Pine-Cone Christmas, the guests said good-night, each declaring that there must be another such time next year.

By and by they were all snugly tucked way under the big buffalo-robes, and one after another the teams and cutters pulled out of the yard with their laughing loads, every one giving a final cheer for the Stebbinses Pine-Cone Christmas!

When it was all over and the family were taking a last look for the night at the presents, the farmer said, almost sharply, to Teacher:

"See here! where'd these things come from? You didn't go off an' buy 'em, did ye?"

Miss Stain laughed. "I said it would be a Pine-Cone Christmas, and it was, from first to last," she insisted.

Then she told them how she had made fancy-shaped bon-bon boxes, which she had sold to the confectioner at Annis for a good price. And that three of the large boxes, which no one seemed to have missed, she had disposed of at a fancy store in that town. The money had purchased the tapers and candy, besides the gifts, and had repaid her for the original outlay in oil, ribbon, etc. But she said nothing about the sash, only "I'm so glad you are pleased."

"But you haven't a single thing!" Benny suddenly cried, with contrition.

"That's so! But here's a kiss, an' I'll never miss in jography again, so long's I live!" cried loving little Bess.

They did not know that Miss Stain, having learned that "it is more blessed to give than to receive," had reaped the richest harvest of pleasure from the Pine-Cone Christmas.

Books make great gifts, and they're always the perfect size.

When you buy one of my books for someone, you're not just giving them a gift, you're also giving me the best gift you possibly can —the ability to make a living doing what I've always wanted to do.

Get it on Amazon |

A Christmas Wish

|

In a seaport town in the late 19th-century Pacific Northwest, a group of friends find themselves drawn together —by chance, by love, and by the marvelous changes their world is undergoing. In the process, they learn that the family we choose can be just as important as the ones we're born into. Join their adventures in

The Tales of Chetzemoka

Tales of Chetzemoka merchandise

"A minute's reading provokes a day's thinking…"

Products inspired by the Tales of Chetzemoka series, books beloved by fans young and old around the world.

For words of wit and advice sage,

I hope you'll like my author page!

History lessons, folks who dare,

Please do share it while you're there!

https://www.facebook.com/ThisVictorianLife

Thank you!

***

If you liked this piece, you might enjoy:

The American Carver (Poem—1887)

Winter Cheer (Poem—1888)

A Christmas Glee (Poem—1890)

Christmas Pensees (Poem—1890)

Back to Historical Articles Index

***

Search this website:

***