Historical Article

1888

Victorian Mourning

The Philosophy of Living

By Hester M. Poole

Good Housekeeping. October 13, 1888, pp. 267—269

Chapter XXV—Mourning and Mourners

Passing out of the shadows

Into eternal day,

Why do we call it dying,--

This sweet passing away? —Anon.

I love and fear not and I cannot lose

One instant this great certainty of peace,

Long as God ceases not I cannot cease. —Helen Hunt Jackson

By Hester M. Poole

Good Housekeeping. October 13, 1888, pp. 267—269

Chapter XXV—Mourning and Mourners

Passing out of the shadows

Into eternal day,

Why do we call it dying,--

This sweet passing away? —Anon.

I love and fear not and I cannot lose

One instant this great certainty of peace,

Long as God ceases not I cannot cease. —Helen Hunt Jackson

Other years came and went. At first they were years of iron, then of silver clouded with alloy and finally years of gold. Love, patience, courage, faith, self discipline and consecration to duty bore their beautiful fruitage. The result of beneficient influences working "without haste, without rest" is as certain as any rule of mathematics. For those who strive for the highest and best all things work together for good. Little by little the shadows break, the rough path grows smooth or the feet that press it receive such accessions of strength that neither thorns can pierce nor rocks can bruise. To such, mistakes are like the hard, rough burrs of the chestnut, which, when ripened and detached by the frosts of Misery, unclose Wisdom's sweet and nourishing kernel.

Life with the Southmayds was a continual climb, but climbing means going upward. Charlie went steadily on, barring a few intervals of unrest when mother's watchfulness kept her first-born true to his best estate. At twenty-four he was, in a small way, an inventor of methods of applying power to machinery, and the royalties received from them lifted the family out of the slough of grinding and patching. George went on enlarging his market gardens, but began to grow restless for larger results. Like many another who develops late, he did not arrive at a full use of his powers till long after twenty.

Meanwhile the cottage had been enlarged by the addition of one good-sized parlor, over which rose Amy's sky-lighted studio, the gathering-place of the clans when all came from work. And Daisy, dimpled, merry little body, took naturally to housekeeping. Under her mother's direction she did the simple marketing and much of the cooking besides keeping account of income and outgo.

The father grew stronger and began to help in many little ways. He had never done anything about the house before, and had not realized how much he missed. Money provided help to do the work and he made the money. Now, Mr. Southmayd saw his mistakes. So, humbly going back to pick up the raveled stitches, he began to weave a new web out of the remnant of life that was left. He was now able to help George a great deal and in his work learned gentleness and patience. Over his wife he watched tenderly; nothing was good enough for her. "Ah!" said he to a friend, "Dora has never once said, "I told you so.'"

Finally the sons went to seek their fortunes in the West. Charlie was the agent of the firm which handdled his inventions in order to introduce machinery into mining, and George determined to be a farmer on a larger scale. They left funds enough to supply the family for a year and Amy's brush would suffice for contingencies. It was the first real break in the family, but the boys were excited over visions of adventure and promised to return with a "pocketful of rocks."

It was a lonely household now, but not an unhappy one. Mrs. Southmayd's philosophy taught her that young birds ought to leave the nest when they are old enough to fly. As she went from the childhood's home so must her own children. It was their nature to. Her first great solicitude was that they might be well prepared for the requirements of practical life physically, mentally and morally; her second, that they might not stray so far away as to be really lost to her. But, in a country like this, who can measure space? Girdled with railways and tied with telegraphs through which, like nerves, thrill thoughts and feelings, there is now nothing distant but distance itself.

Thirty uneventful days went by and then, between one dawn and sunset, Mrs. Southmayd found herself a widow. Sitting on the porch in the sunshine another paralytic seizure brought instant unconsciousness to her husband and, in a few hours, he ceased to breathe. A letter from the boys that very morning, brimming over with descriptions and cheerful prognostications, lay on their father's knee when the stroke fell. They were about to start for the Black Hills and could not tell where they might be from one week to another. In this awful time Mrs. Southmayd and her daughters wee alone. At first it seemed too hard to bear. How could she go through it all?

But the lessons of a life-time are not forgotten in an hour. Alone with the dead form of him whom she had always cherished with a love divine, she found peace and consolation. To the world he had been a failure, not to her.

Who knows? Each year, as does a wheat seed, dies,

And so God harvests His eternities.

She had witnessed the true and tender spirit of one whose errors had been those of great worldly ambition, struggle out and up through those events which the world calls defeats but the angels call victories. Was not that a true triumph in the end? Then these lines of Phebe Cary sang themselves in her consciousness:

I see the feet that fain would climb

You but the steps that turn astray;

I see the soul, unharmed, sublime

You but the garment and the clay.

You see a mortal, weak, misled,

Dwarfed ever by the earthly clod;

I see how manhood, perfected,

May reach the stature of a God.

And so, looking below the surface of life into its tremendous realities, she was not as one uncomforted. He was gone from temptation, trial and error, but not from that boundless Love which sustains and contains the life it has once evolved. We learn to walk through stumbling and know success only after failure. Through ignorance, selfishness and error come wisdom, selfhood and truth. Goodness is the final significance and crown of all created things, and toward it all steps must lead through pathways devious and manifold. In the words of Browning:

To know

Rather consists in opening out a way

Whence the imprisoned splendor may escape,

Than in effecting entry for a light

Supposed to be without.

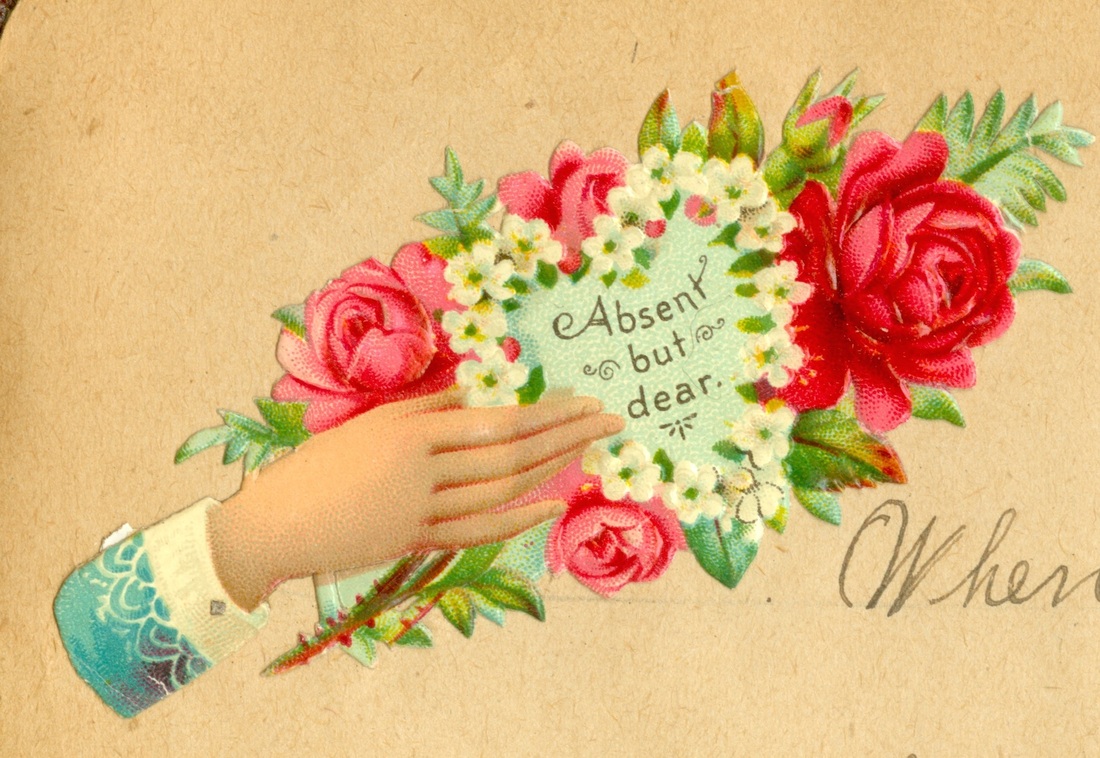

After the first stunning sense of bereavement, soul triumphed over sense, religion over grief. Wherever in God's universe might be the lover of her youth, Mrs. Southmayd felt that he was sheltered safe by that love that ever works to wise ends, even through that which the world calls Death. He was gone, but what is the loss of sense to souls who love and trust one another through silence and seeming separation? The wires of communication may be down, but wires are organs, not persons.

And so the last rites over the cast-off body of Mr. Southmayd were simple, beautiful, and as near may be, private. No stream of gossiping and officious helpers were present. All was quiet as the vestibule of some holy place.

Mrs. Southmayd preferred cremation to internment, but out of deference to custom would not press the point. She believed the world would come to that mode of disposal for the discarded form, the chrysalis of the soul, but prejudice is a rank weed and one pair of weak hands could not dislodge enough to make any diminuation of the growth. There were a few friends gathered to hear the fifteenth chapter of Corinthians read by one who knew and loved the family, and then a simple ritual which expresses the reverence and the hopes of humanity. There were sweet voices united in consecrated hymns, and lovely flowers and —silence and solicitude.

To the horror of Aunt Ruth, her niece refused to wear mourning. Mrs. Southmayd regarded the custom as fit only for atheists. "My husband is not dead," said she, "why should I appear as if he were? According to your own faith, Aunt, death is swallowed up in victory. Why wear a somber, gloomy robe in token of victory? If death were the end of life then might we well shroud ourselves in the habiliments of woe. Black is the hue of despair; ought Christians to wear this symbol of gloom and grief? With me it is a matter of principle rather than taste, to abjure mourning. Either philosophy or religion should forbid."

Doubtless there are many who conceive themselves comforted by crape and bombazine and their feelings ought to be respected. We are greatly the creatures of habit. Among the Hebrews the conventional expressions of grief consisted in tearing garments, cutting the hair and beard and going about bareheaded and barefooted, weeping and smiting the breast. The Greeks kept themselves secluded, wore coarse black garments and wailed bitterly. During the empire women wore white mourning in place of black —a cheerful custom, at least. Among barbarians mourning rites are horrible, including burning and amputation. In the Sandwich Islands the natives paint their faces and knock out their front teeth.

The Chinese, more hopeful than the Caucasians, believe their friends are alive and happy in some distant clime and so use white instead of black. Even the Turkish mourning is cerulean, to represent the sky to which their loved have flown, while the Ethiopians typify the dust of whicch they are made by the brown they don on funeral occasions. Everywhere it is conventional and more or less barbaric. How unlike a true conception of that "other world" of Mrs. Stowe:

And so the last rites over the cast-off body of Mr. Southmayd were simple, beautiful, and as near may be, private. No stream of gossiping and officious helpers were present. All was quiet as the vestibule of some holy place.

Mrs. Southmayd preferred cremation to internment, but out of deference to custom would not press the point. She believed the world would come to that mode of disposal for the discarded form, the chrysalis of the soul, but prejudice is a rank weed and one pair of weak hands could not dislodge enough to make any diminuation of the growth. There were a few friends gathered to hear the fifteenth chapter of Corinthians read by one who knew and loved the family, and then a simple ritual which expresses the reverence and the hopes of humanity. There were sweet voices united in consecrated hymns, and lovely flowers and —silence and solicitude.

To the horror of Aunt Ruth, her niece refused to wear mourning. Mrs. Southmayd regarded the custom as fit only for atheists. "My husband is not dead," said she, "why should I appear as if he were? According to your own faith, Aunt, death is swallowed up in victory. Why wear a somber, gloomy robe in token of victory? If death were the end of life then might we well shroud ourselves in the habiliments of woe. Black is the hue of despair; ought Christians to wear this symbol of gloom and grief? With me it is a matter of principle rather than taste, to abjure mourning. Either philosophy or religion should forbid."

Doubtless there are many who conceive themselves comforted by crape and bombazine and their feelings ought to be respected. We are greatly the creatures of habit. Among the Hebrews the conventional expressions of grief consisted in tearing garments, cutting the hair and beard and going about bareheaded and barefooted, weeping and smiting the breast. The Greeks kept themselves secluded, wore coarse black garments and wailed bitterly. During the empire women wore white mourning in place of black —a cheerful custom, at least. Among barbarians mourning rites are horrible, including burning and amputation. In the Sandwich Islands the natives paint their faces and knock out their front teeth.

The Chinese, more hopeful than the Caucasians, believe their friends are alive and happy in some distant clime and so use white instead of black. Even the Turkish mourning is cerulean, to represent the sky to which their loved have flown, while the Ethiopians typify the dust of whicch they are made by the brown they don on funeral occasions. Everywhere it is conventional and more or less barbaric. How unlike a true conception of that "other world" of Mrs. Stowe:

Sweet hearts around us throb and beat,

Sweet helping hands are stirred,

And palpitates the vail [sic] between

With breathings almost heard.

In multitudes of cases families put into pompous funeral ceremonies and costly mourning enough to save them from impending want. Who can suppose that the departed would desire such trappings, when no one is benefited and no real respect shown by the unwisdom? Modern oblations take a distant form but amount to the same thing as the ancient. A sacrifice upon the altar of show and ceremony is a sacrifice still. Where the wealthy indulge, the poor certainly will. A costly casket, a long line of carriages, flaunting crape and an empty larder, debts, anxiety and wretchedness. Nore can they abate one jot the pangs of separation, which can only be assuaged by trust in that Providence which comprehends all we can ever know of deathless and exalted affection.

As a protest against a more than idle parade, the Church of England "Funeral and Mourning Association" has lately been founded, and its good effects are already apparent. It deprecates ostentation, urges the exercise of simplicity and the disuse of crape, scarfs, feathers, velvet trappings, excessive floral decorations and a great setting forth of "funeral baked meats" which, in some rural districts, attract crowds of people who come out of curiousity and to enjoy a feast.

A similar society is being established in New York city which embraces among its membership prominent clergymen of various denominations and dignitaries of the Protestant Episcopal church. While it meets with the favor of right minded people it cannot be expected to become immediately fashionable.

To be considerate and tender of friends while they are with us is better than thoughtlessness when they are present and an elegant monument after their departure. "Settle the account with thy conscience," wrote Irving. "If thouh art a friend and hast wronged by thought or word or deed the spirit that generously confided in thee, ... be sure that every unkind look, every ungenerous word, every ungentle action will come thronging back upon thy memory and knock dolefully at thy soul. Be sure thou wilt pour the unavailing tear, bitter because unavailing."

But, as in all else, temperments differ here. Some cherish the luxury of woe, through sentimental reasons, just as others are happy through a living faith. "You are cheerful, Father Bushness," said a man to his aged pastor who had just buried the form of the last member of his family. "I wonder how you can be after your great loss."

"How can I not be?" replied the sage. "If you were on the way to a beautiful country and had a dark and turbid river to cross before reaching its shores, would you not rather stay on the back and see the members of your family safely embarked before taking passage yourself? That is my case. My loved ones have no more to suffer here and that is happiness to me. In a few days I, too, shall set sail. And I shall go without one anxious look backwards toward any dependant on me, who are left behind. Give me joy! Our Father is kind to me and mine."

But, wherever there is not a living faith in the Eternal Good there will be wailing and mourning. Others, too, will consider Mrs. Southmayd's decision not to wear crape, as unfeeling. Aunt Ruth, as well as she could, made up the deficiency. Nothing suited her better than to putter over the depth of a fold or the draping of a veil. For those likewise interested Aunt Ruth gave these directions in regard to fashion in mourning:

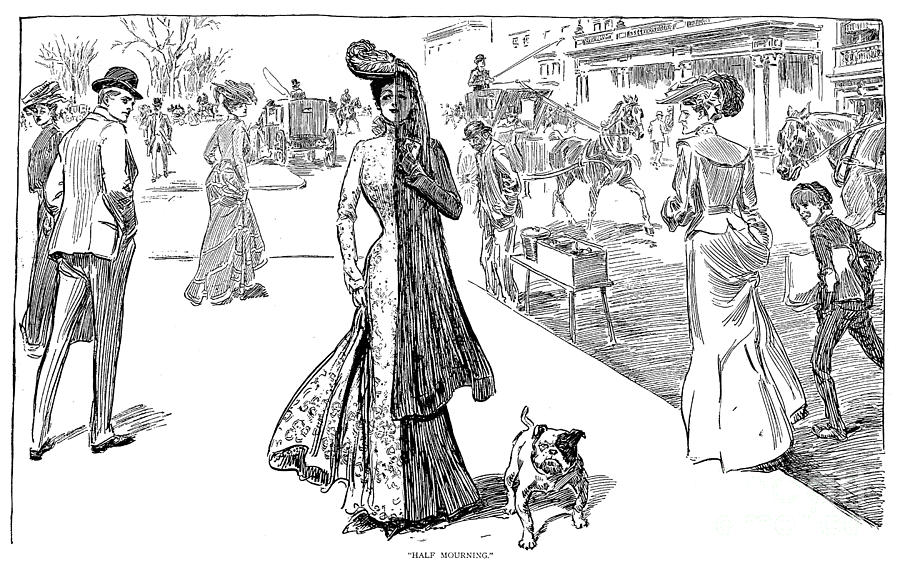

"Black worn for parents should not be dispensed with for at least eighteen months, during which time no place of amusement can be visited and no invitations to dinners, lunches or parties accepted. No one wearing mourning should ever think of going to a theater. It is incongruous. Mourning may be mingled with white at the beginning of the second year and finished with the various tints of purple.

"For a widow no mourning can be too somber. Henrietta cloth is the best material known. The veil, during the first half year, is four yards long and nearly covers the figure in the front and the back. It is fastened to the bonnet by mourning pins and may be shortened one-half or even moe toward the end of the first year, when it is thrown back from the face. The bonnet should be small to show the widow's cap. Jewelry, feathers, fringes, silk and velvet trimmings are in the worst of taste. Jet is admissible.

"After laying aside crape, black bunting and grenadine are appropriate. Black ear-drops should be worn, if any, and a black silk-guard chain for the watch, while handkerchiefs and note paper show mourning borders, either wide or narrow.

"Crape is not an absolute necessity in the mourning garb except for husband or child, and it should never be used by the young, who wear simple black for a year, then quiet hues for the next six months.

"Those who wear black consider it a protection from many occurrences and inquiries which might otherise be difficult to encounter. It tells its own story, needing no explanation and demanding only silent sympathy."

As a protest against a more than idle parade, the Church of England "Funeral and Mourning Association" has lately been founded, and its good effects are already apparent. It deprecates ostentation, urges the exercise of simplicity and the disuse of crape, scarfs, feathers, velvet trappings, excessive floral decorations and a great setting forth of "funeral baked meats" which, in some rural districts, attract crowds of people who come out of curiousity and to enjoy a feast.

A similar society is being established in New York city which embraces among its membership prominent clergymen of various denominations and dignitaries of the Protestant Episcopal church. While it meets with the favor of right minded people it cannot be expected to become immediately fashionable.

To be considerate and tender of friends while they are with us is better than thoughtlessness when they are present and an elegant monument after their departure. "Settle the account with thy conscience," wrote Irving. "If thouh art a friend and hast wronged by thought or word or deed the spirit that generously confided in thee, ... be sure that every unkind look, every ungenerous word, every ungentle action will come thronging back upon thy memory and knock dolefully at thy soul. Be sure thou wilt pour the unavailing tear, bitter because unavailing."

But, as in all else, temperments differ here. Some cherish the luxury of woe, through sentimental reasons, just as others are happy through a living faith. "You are cheerful, Father Bushness," said a man to his aged pastor who had just buried the form of the last member of his family. "I wonder how you can be after your great loss."

"How can I not be?" replied the sage. "If you were on the way to a beautiful country and had a dark and turbid river to cross before reaching its shores, would you not rather stay on the back and see the members of your family safely embarked before taking passage yourself? That is my case. My loved ones have no more to suffer here and that is happiness to me. In a few days I, too, shall set sail. And I shall go without one anxious look backwards toward any dependant on me, who are left behind. Give me joy! Our Father is kind to me and mine."

But, wherever there is not a living faith in the Eternal Good there will be wailing and mourning. Others, too, will consider Mrs. Southmayd's decision not to wear crape, as unfeeling. Aunt Ruth, as well as she could, made up the deficiency. Nothing suited her better than to putter over the depth of a fold or the draping of a veil. For those likewise interested Aunt Ruth gave these directions in regard to fashion in mourning:

"Black worn for parents should not be dispensed with for at least eighteen months, during which time no place of amusement can be visited and no invitations to dinners, lunches or parties accepted. No one wearing mourning should ever think of going to a theater. It is incongruous. Mourning may be mingled with white at the beginning of the second year and finished with the various tints of purple.

"For a widow no mourning can be too somber. Henrietta cloth is the best material known. The veil, during the first half year, is four yards long and nearly covers the figure in the front and the back. It is fastened to the bonnet by mourning pins and may be shortened one-half or even moe toward the end of the first year, when it is thrown back from the face. The bonnet should be small to show the widow's cap. Jewelry, feathers, fringes, silk and velvet trimmings are in the worst of taste. Jet is admissible.

"After laying aside crape, black bunting and grenadine are appropriate. Black ear-drops should be worn, if any, and a black silk-guard chain for the watch, while handkerchiefs and note paper show mourning borders, either wide or narrow.

"Crape is not an absolute necessity in the mourning garb except for husband or child, and it should never be used by the young, who wear simple black for a year, then quiet hues for the next six months.

"Those who wear black consider it a protection from many occurrences and inquiries which might otherise be difficult to encounter. It tells its own story, needing no explanation and demanding only silent sympathy."

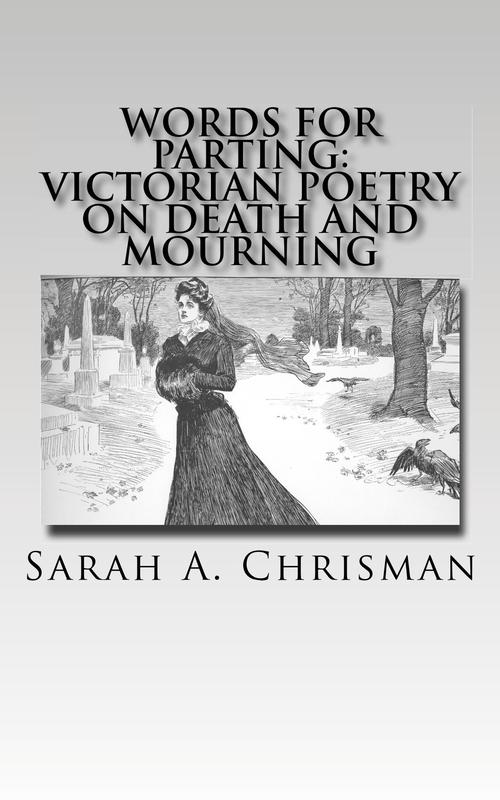

Words For Parting

Victorian Poetry on Death and Mourning

Love and grief and the two most private, and at the same time the most universal of all human emotions. It is for love that we remember the dead: love of their spirits, love of their vibrancy, love of the good deeds which they did and which live on after them. The poems in this collection were all written by grieving hearts who have now themselves passed over into that great mystery. We can not truly know what death is, yet we know it will come to all of us. In ancient times when a friend told the philosopher Socrates that his judges had sentenced him to death he responded, "And has not Nature passed the same sentence on them?"

Inasmuch as there can ever be any comfort for those left behind, part of it lies in knowing that death is a reflection of life. When it comes we cry, then we take our first faltering steps towards understanding. In time we become accustomed to this manifold enigma which nature has given us, and then ultimately we look towards the future with hope.

If this little book of poems may be of some help to those in sorrow by reminding them they are not alone, then it will have done its work.

Compiled and edited by Sarah A. Chrisman, author of the Tales of Chetzemoka series, This Victorian Life, and others.

Amazon

***

If you are interested in Victorian mourning customs that are still practiced, check out WISP Adornments. Angela Kirkpatrick is a modern jewelry artist who makes mourning jewelry in the Victorian style:

WISP Adornments on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/Wisp-Adornments-140903286083078/

WISP Adornments on Etsy:

https://www.etsy.com/shop/WispAdornments

***

***

External links to other pieces related to Victorian mourning:

"All is Vanity": Image from 1892, with modern commentary

"An Anniversary": Artwork from 1893

"A Retrospective Widow": Cartoon from 1892

"The Evening": Artwork by Charles Dana Gibson, 1899, republished in 1906

"Etiquette of Mourning" article from Collier's, 1882

(Google Books link)

"The House of Mourning" A farce from 1844, Godey's

(Google Books link)

1861 Mourning attire

1870 Mourning dress and bonnets from The Peterson Magazine

1871 Mourning attire from Harper's Bazaar

1873 Half-mourning from The Peterson Magazine

1877 Ladies' and children's mourning dresses from Harper's Bazaar

1883 Mourning attire from The Peterson Magazine

1883 Mourning dresses from The Queen

1883 Mourning dress from The Queen

1883 Plastron for mourning from The Peterson Magazine

1885 Mourning dress

1886 Mourning dress from The Peterson Magazine

1889 Deep mourning outfit from The Peterson Magazine

1890 mourning dresses, for ladies and children

1891 mourning attire from Harper's Bazaar

"A Supernatural Swindle" (Humorous ghost story, 1896)

http://www.thisvictorianlife.com/a-supernatural-swindle-fictionmdash1896.html

"The Bottomless Grave" (Another hilarious tale of the supernatural)

Google Books link

***

To cheer you up after all this mourning, check these out:

Encouraging Quotes (Various)

If you Would Be Happy (1887)

Maxims for the New Year (1889)

If you enjoy our website, be sure to check out my books!

In a seaport town in the late 19th-century Pacific Northwest, a group of friends find themselves drawn together —by chance, by love, and by the marvelous changes their world is undergoing. In the process, they learn that the family we choose can be just as important as the ones we're born into. Join their adventures in

The Tales of Chetzemoka

Anthologies:

True Ladies

and Proper Gentlemen

Non-fiction:

***

Please show your support for all our hard work by

liking Sarah's author profile on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/ThisVictorianLife

Thank you very much!

Search this website:

***