The story "Three Warnings" was written by Lucy B. Hooper and published in Peterson's Magazine in 1890. I transcribed it from an antique volume in our private archive, and it appears in my anthology

A Bouquet of Victorian Roses:

19th-century Remarks, Poetry and Short Stories About the Queen of Flowers

I find, my children, that I am growing old, and that it behooves me to write out for your perusal hereafter the history that it is essential you should know, and which, singular as the details may appear under the influence and scepticism of this nineteenth-century, it is still strictly true. I have to relate not only my own personal experience, but that of two of our ancestors.

We have been a family appparently highly favored by fate. You have heard, doubtless, of the talismans possessed by certain noble families, and which were supposed by some mysterious power to bring good-fortune to their owners. Such a one is the famous glass goblet known as the Luck of Eden Hall, and celebrated in verse by Longfellow. We, the Martels, originally of France, but for three generations citizens of the United States, have in our keeping a talisman more potent and more singular in the manifestations of its powers than any other relic of the kind, of which I have ever heard. For it does not simply confer good-luck on its possessors, but it acts the part of a guardian angel.

You know, my children, that our family is a very ancient one. We are supposed to derive our descent from the heroic and intellectual Charles Martel, who governed France so wisely as Mayor of the Palace under the feeblest of the early kings of France. Respecting our claim to consider this great man as our ancestor, I have nothing definite to allege. But this I do know: that the family was an old and honorable one, a race of students, of artists, and of men renowned for their learning and in some cases for their skill as workers in gold and silver and precious stones. Benvenuto Cellini himself was jealous of the talent of Antoine Martel, who was patronized by Diana of Poitiers, and who made for that lady a table-service in gold, wrought with the story of Diana and Endymion, and to whom Queen Claude of France confided the task of mounting her ancestral jewels, the ducal diadem and other crown-jewels of Brittany, into ornaments better fitted for the wife of Francis the First to wear. But it was the father of Antoine, the Martel who flourished in the reign of Louis the Eleventh, who was the true chief of our family. Gilles Martel was a noted physician and was also given to dabbling in astrology and alchemy and other occult sciences. He was in high favor at one time with his keen-witted but superstitious sovereign, and is said to have predicted in a very startling way the tragic fate that some years later befell the reknowned Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. Also, he was much in favor with King Louis's delicate and deformed daughter, the Princess Joan, and did much to alleviate her sufferings during her frequent attacks of illness. During the brief period that she was Queen of France, she made him her court-physician; and when, after her repudiation by her husband, she retired to a cloister, it was by her wish that he still continued his ministrations. I have dwelt thus long on the history of Gilles Martel for a reason that will presently appear.

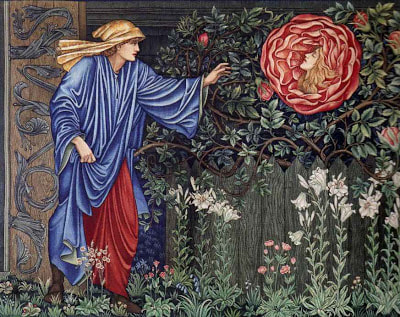

You are all of you familiar with the subject and aspect of the vast piece of ancient tapestry that has always covered one of the sides of my library-wall, and some amongst you have begged me at times to remove it and to fill the space it occupies with an extra book-case, which is, I confess, much needed. Also, I remember the amazement evinced by you all when, on the occasion of a fire, caused by a defective flue, breaking out in our spare bed-room, I hastened to detach the old tapestry and to bear it out of harm's way before attempting to save anything else, and, in fact, as soon as I had ascertained that your mother and you were out of danger. The fire was extinguished, it is true, without doing any material damage; but you apparently thought that I might have begun by saving our plate and our pictures and also your mother's diamonds. Children, the old tapestry is our Luck of Eden Hall; it is more—it is, as I have said before, our guardian angel.

You remember it, doubtless: the faded group of personages in the foreground, one of whom—a tall, gray-bearded, grave-looking gentleman, wearing a loose black robe and a mortar shaped cap trimmed with fur—is, according to family tradition, the portrait of our ancestor, the learned Doctor Gilles. The other individuals represent certain of the great physician's kinfolk, who had made honorable names for themselves as warriors or as ecclesiastics. But it is only with the figure of Gilles Martel that we have to do, and also with the border of the tapestry, on which is worked at intervals groups of red heraldic roses, each composed of three flowers, these groups being separated by square spaces. In each of these squares is delineated a curious little allegorical picture, the meaning of which has never been explained. The whole piece is in a state of perfect preservation and is a singularly fine specimen of the tapestry-work of the fifteenth century. I need not assure you that it is immensely valuable. But on no consideration, nor at any price that may ever be offered to you, must you be persuaded to part with it. I do not think that you will be willing to contemplate even the possibility of disposing of it, once you have concluded the perusal of this paper.

I must begin my story with the transcription, or rather an abstract, of a document bequeathed by our ancestor, François Martel, who was the grandson of the learned Gilles, and who flourished in the sixteenth century. From his father Antoine, he had inherited great taste and skill as a worker in metals. As a youth, he had embraced the Reformed religion and was a Huguenot of an ardent and pronounced type. This fact did not hinder him from being extensively patronized by the less bigoted of the nobles at the court of Charles IX, though of course he got but few orders from the followers of the Duke de Guise. But, when the bold Protestant hero, Henry of Navarre, came to Paris to wed Marguerite de Valois, the star of the Huguenot goldsmith was in the ascendant. There are extant a number of his drawings of designs for articles of plate and jewelry manufactured by him for the royal pair. Amongst these is a wreath of daisies to be wrought in diamonds, as a gift for the bride, which is altogether exquisite and artistic. But I not think that this charming device was ever reproduced in gold and gems.

Now comes the first strange episode in my strange story. I derive my facts from the parchment record drawn up by François Martel himself, and by him bequeathed to his descendants jointly with the piece of tapestry, which had been left to his father Antoine by Doctor Gilles and which had always been held in high esteem by both father and son, on account of the group of family portraits. The writer declares—I translate from the quaint antique French without attempting, as indeed, it would be vain to do, to reproduce its peculiarities in English—that, one pleasant evening early in June in the year 1572, he was seated alone in his study, having need, he writes, of much meditation concerning the design of the silver ewer ordered from him by Admiral de Coligny. He is especially careful to note that his supper had been of the simplest, consisting of some dried pears and comfits and a single cup of Cyprus wine. He is certain that he had not fallen asleep, as he had been greatly engrossed with his drawings and also much tormented thereby, as he could not work the armorial bearings of the Colignys into his design in a satisfactory manner. Finally, having gotten his sketch into shape, he leaned back in his chair for a few moments' rest and reflection. His eyes naturally fell upon the tapestry which hung upon the wall, and upon which the rays of a full and unclouded summer moon were brightly shining, and especially upon the figure of his grandsire, which was prominent in the foreground. Suddenly it seemed to him as if this figure were slowly rising out of the tapestry; that is to say, it was no longer a flat surface, but was assuming the rounded and prominent contours of a living being or of a graven image. As he gazed, the change became more accentuated and complete, and finally the form took motion as it had assumed shape, and steeped from the hangings to the floor, slowly advancing till it came within a few paces of the table at which the astonished goldsmith sat. He makes special record of the fact that he was not terrified by the apparition, though greatly awed and wonder-stricken.

"My grandson François,": said the form, "I come to warn you, as I shall have the power to warn my descendants hereafter, of a great and impending danger. When you receive from an unknown hand three red roses, be assured that the peril is at hand. Then leave France, with your family and possessions, and without delay. Remember the token—three red roses; and thereafter linger not, but depart at once." Then the room was darkened, as though a cloud had passed over the moon; and, when the light shone out again, the figure had returned to the tapestry, and the room had resumed its wonted aspect.

My ancestor goes on to say that he was deeply impressed with the mysterious warning, and that for some days he thought of little else. Then he became absorbed in the preparations for the wedding of the King of Navarre, and gradually the singular occurrence of that June night faded from his mind. The day of the royal marriage, the 18th of August, at last arrived, and François Martel mingled with the throng at the doors of the Church of Notre Dame, to witness the ceremony, which was performed by the Cardinal de Bourbon and which took place on a lofty stage erected outside of the portal of the catheral. Absorbed as he was in gazing at the bridal party, he was only vaguely conscious of a gentle touch on his right hand; and, when the marriage was at an end and he turned away to bend his steps homeward, he was amazed to find that he was mechanically holding three red roses that had apparently been slipped into his hand by some unknown personage. He looked around and questioned some of the bystanders as to the giver of the flowers; but no one had noticed the person who had left them in Messire Martel's graps, though several had seen the roses and remarked upon their beauty.

So greatly was he impressed by this fulfillment of the phantom's announcement, that he hastened to put together all his possessions in the shape of money, jewels, and and precious metals, not forgetting—as he specially records—the piece of tapestry, with other hangings of great price; and he embarked with all his family at the Louvre wharf, on a bark hired by himself, for England, two days after the king's marriage. He has not failed to record the stupefaction and indigation of his good wife, Dame Brigitte, and also of his elder children, at being thus hurried away on what, in those days, was a most stupendous journey, and being forced to lose all the public rejoicings on the occasion of the royal wedding. Also, he has set down his own doubts and misgivings in having undertaken so grave a step as the breaking-up of his home and a flight from his native land, on the word of an apparition and the token of three flowers, that might indeed have come into his possession by accident. But hardly had they arrived in London, nor were the family fully established as yet in a hostelry at Southwark, when the tidings of the bloody massacre of the eve of St. Bartholomew, the 24th of August, reached London. François Martel, as a wealthy and noted Huguenot, would, with all his family, have perished on that night of horrible slaughter, had he disregarded the warning of the phantom and the token of the three roses.

The remainder of the fugitive's history was prosperous and uneventful. He opened a golsdmith's shop at Cheapside, and, as a persecuted Huguenot, his story excited a good deal of sympathy amongst the nobles at the court of Elizabeth. The great queen herself condescended to send for him and to order from him a pomander-chain and some minor matters. Thus patronized by royalty, he flourished exceedingly and was contented and happy in his English home. With this assurance, the document due to his patient pen, and which I have greatly abridged, comes to an end.

The fortunes of the Martel family thereafter have for over two centuries nothing to do with the tapestry portrait of Gilles Martel. After the death of Messire François and the accession to the French throne of Henri IV, his widow and children returned to Paris. In due time, the head of the family married a Catholic lady, and their children were educated in their mother's faith, so that the Martel family was no longer liable to persecution on account of its Protestantism.

In the reign of Louis XIV was founded the banking-house of the Brothers Martel by the two last survivors in the direct line of the descendants of Dr. Gilles. These gentlemen, Jehan and Olivier Martel, founded for the family a new era of prosperity. We, my children, are descended from the first-named, his brother Olivier having died unmarried. During all these years, and despite the journeys and changes of fortune of the family, the piece of tapestry and the narrative of François Martel were always religiously guarded and cared for by the head of the house. Hence the remarkable preservation in which the first-named relic has come down to our day.

I have now come to the epoch of the delivery of the second warning, and I translate from the family papers in my possession, so that such of my descendants that may be unacquainted with the language spoken by their ancestors may read this statement and comprehend the facts as they occurred.

At the accession of Louis XVI to the throne of France, the once numerous race of the Martels had dwindled down to a single survivor, Jules Martel, a prominent and prosperous banker, who had accumulated great wealth, and who had in consequence persuaded the noble family of De Ponteveze to overlook his descent from the Huguenot goldsmith and to bestow one of their demoiselles on him in marriage. Jeanne de Ponteveze was very willing to become Madame Martel, her choice lying between her acceptance of her wealthy suitor and seclusion in a convent. She obtained from the king permission to join her own noble name to that of her husband, and the pair were thereafter known as M. and Mme. Martel de Ponteveze. There was talk of the revival for the husband of one of the dormant titles belonging to the wife's family—a baronry, I believe; but somehow this honor was postponed till titles had become dangerous things in France for their wearers, and the project was dropped. Meantime, the lady had become the close friend and confidante of more than one of the great ladies of the court, the Countess Jules de Polignac and the Princess de Lamballe being of the number. It was said that Madame Martel obliged her aristocratic friends with timely loans of large sums of money through the mediation of her husband, a form of assistance that was peculiarly acceptable in those days of unbounded extravagance of high play at cards. Altogether, the last survivor of the descendants of Gilles Martel had become thoroughly affiliated with the court-party amongst the French aristocracy. His treasured piece of ancestral tapestry decorated the chief drawing-room of his sumptuous hotel in Paris. It was something in his favor, with his new circle of friends, to be able to show that he really possessed ancestors, and one at least, in the person of the learned adviser of Louis XI, of whom he could well be proud. As to the apparition and the warning and the token of the three red roses, as related by the goldsmith François, the astute banker had long before set them down as the figments of an overexcited brain, or as a dream and a series of curious coincidences at the most.

He has not left on record the precise date nor the exact circumstances attending the second appearance of the figure of Gilles Martel. He states that it was on a moonlit night, and that the form descending from the tapestry addressed him in almost the exact words that François Martel had so carefully written down. Once again was the descendant of the learned doctor warned to flee from France, and once more were three red roses indicated as the token that danger was at hand. And then the figure seemed to retreat backward to the wall, and became again incorporated with the tapestry. Jules Martel was at first less moved by the vision or dream, coupled as it was with the same experience that had befallen his ancestor, than might have been imagined. But he relates in his diary how for some weeks he waited and watched, and in the vague expectation of receiving the token-flowers; but, as time went on without farther incident, he became persuaded that he had fallen asleep on one of the couches in the drawing-room, and had simply dreamed a remarkably vivid dream, colored by his remembrance of the story told by his ancestor.

Time wore on, and the thrilling scenes and dramatic events that preceded the actual outbreak of the great Revolution filled the minds of all men. Jules Martel and his wife, now thoroughly affiliated with the most ultra division of the royalists party, were actors in more than one of the incidents that diversified the prologue to that terrible historical tragedy. And so it chanced that they were present at the banquet given by the officers of the French and Swiss Guards at the theatre of the palace of Versailles. It was a scene never to be forgotten: the fair queen, pale beneath her rouge, the cries and excitement and eager drinking of the healths of the royal party by their military guests, the orchestra pouring forth the melancholy yet impassioned strains of "O Richard, O my king!" the tricolor trampled under foot, the soldiers scaling the boxes to receive from the hands of the ladies the white cockade emblematic of their loyalty; it was a moment whose fervor and enthusiasm might well have persuaded the most lukewarm partisan of royalty that the affections of the nation were really centered on their king and queen. Madam Martel de Ponteveze had just attached one of the rosettes of white ribbon to the shoulder of an ardent young lieutenant, her own nephew, and her husband had smiled his approval of the act, when, on turning from the stage, he saw lying before him, on the ledge of the box, three red roses.

It was rather strange that he took heed at once and practically to the warning of the token-flowers. But Jules Martel was a keen-witted and sensible man, and was not wholly blinded by his prejudices in favor of the aristocratic set in which he had gained a precarious footing by his marriage. He was in reality a roturier[1], and he knew it, and he had doubtless often meditated with many misgivings over the coming tempest, whose dark clouds and muttering thunder could be ignored by no such intelligent observer as himself, and especially one whose senses were not blunted by the prejudices of race. His own convictions lent weight to the warnings of the phantom and the flowers. He hastened to transfer to England his family and such of his possessions as could be taken thither. His banking-house was left in the charge of one of his junior partners, and, long before the full horror of the Reign of Terror had burst upon his native land, he was established, with his family, in a pleasant quarter of London. There he and his wife came to be considered as a very providence for the exiled French nobles. Many of the kinsfolk of Madame Martel—and among them the young Lieutenant de Ponteveze, who had figured at the banquet at Versailles—perished by the guillotine, a fate that would doubtless have befallen both Jules Martel and his wife, had not that strange vision interposed to save them.

Such, my children, was the experience of my great-great-grandfather. It was I myself who was to be the next of the descendants of Gilles Martel to receive the spectral warning…

RSS Feed

RSS Feed