Several fans have asked me where I got the idea for Nurse McCoy, a character in my historical fiction series. The explanation requires a bit of background in nursing history, and mid-May seems an appropriate time to tell the tale. May 12th is Florence Nightingale's birthday; it is also International Nurses Day. This is not a coincidence.

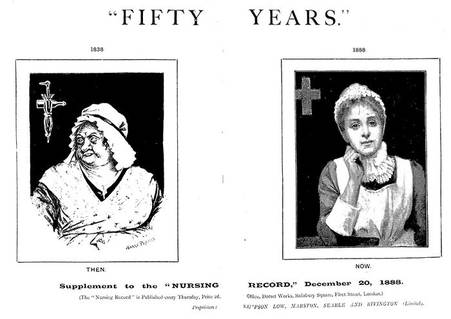

In the twenty-first century, if someone were asked to describe qualities that make a good nurse, they might list kindness, patience, generosity, and a strong work ethic. But before Nightingale rose to prominence public opinion of nurses was very different. A nineteenth-century nurse reported, "When I first began my hospital training, hospital nursing was thought to be a profession which no decent woman of any rank could follow. If a servant turned nurse, it was supposed she did so because she had lost her character. We have changed all that now." By the time of the interview nurses were held in quite high esteem, their image being very similar the present one. The Victorian nurse who witnessed these changes credited them entirely to Florence Nightingale.

Two years before Nightingale's birth, the poor reputation of nurses in the English-speaking world was embodied by a minor character in Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein: "The sound disturbed an old woman who was sleeping in a chair beside me. She was a hired nurse, the wife of one of the turnkeys, and her countenance expressed all those bad qualities which often characterize that class. The lines of her face were hard and rude, like that of persons accustomed to see without sympathizing in sights of misery. Her tone expressed her entire indifference…" A charity hospital in New York before the organization of a nursing school there was described in ghastly terms: "In the fever ward (forty beds) the only nurse was a woman from the workhouse, under a six-month sentence for drunkenness."

At this time, medicine in general was becoming increasingly professionalized. In 1858 the British General Medical Council officially began differentiating between "qualified" and "unqualified" practitioners. The United States had only four medical colleges in 1800, but by 1877 this number had swelled to seventy-three. The American Medical Association was organized in 1847 (seven years before Nightingale made her famous departure to serve as a nurse in the Crimean War), and between 1864 and 1902 another fifteen specialty medical groups appeared in the U.S.

Nightingale was the daughter of a wealthy squire, yet despite nursing's vulgar reputation she felt herself drawn to caregiving. Starting in 1844 Nightingale examined conditions in both civil and military hospitals all over Europe. Paid nurses, as described above, were looked on very poorly when Nightingale was a young woman but religious orders who provided healthcare were accorded respect. It was to these Sisters that Nightingale looked for guidance and training. She received training in health-care practices from Protestant Deaconesses in Kaiserswerth (in what is now Germany), and with the Catholic Sisters of St. Vincent De Paul in Paris.

When Nightingale returned to England she took over management of a London Sanitarium for Governesses. But it was her work nursing soldiers in the Crimean War that made her name a household word.

Conditions in British military hospitals on the Crimean front in 1854 were described in hellish terms: "miles of fetid and over-crowded corridors, without proper beds and bedding, without proper food, medicine, or attendance, and above all, without the means of breathing fresh air." Besides wounds received in actual battle, the soldiers were suffering frostbite, scurvy, dysentery, camp fever and cholera. The infectious cases were jumbled indiscriminately with the men who had open wounds, and lack of sufficient caregivers resulted in a situation where injuries went undressed for five or six days and wounds became clogged with maggots.

Britain's Secretary of War, who "knew that a woman's hand and brain was needed at the Crimea", wrote to Nightingale asking her to take charge of nursing on the Crimean front and improve the situation. She, having heard of the conditions, had already written to the same Secretary of War asking permission for this very duty, and their letters crossed in the mail. She left for the war on October 21, 1854. The small group of women who accompanied her in this endeavor had been carefully chosen for their characters as well as proven abilities to care for the sick: they included the daughter of a bishop, ten Roman Catholic Sisters of Mercy, and ten Protestant Sisters, and a few carefully chosen lay nurses.

They brought portable cooking stoves with them, which immediately upon arrival were put to use producing nourishing food for the starving patients. Within a week they established a separate kitchen and engaged civilian cooks, at which point Nightingale's nurses could more thoroughly devote themselves to the vital task of sanitation. They raised private funds to build baths, wash-houses, and additional kitchens.

Nightingale would be on her feet for twenty hours at a time. When bureaucratic red tape failed to provide requisition orders for needed materials, she simply commanded the male orderlies to break into the warehouse and took out the necessary supplies.

Under Nightingale's supervision, mortality in British military hospitals on the Crimean front was reported to drop from sixty percent to only a little over one percent. The soldiers, many of whom were from humble backgrounds, were so in awe of this high-born noblewoman and her tender care of the suffering that they wrote home about kissing her shadow when she came close to them.

The presence of an aristocratic lady elevated the morals of the men at the same time she ministered to their physical needs. One man reported, "Before Miss Nightingale came, there was such cussin' and swearing', and after that it was as holy as a church."

When Nightingale returned to England from the Crimea, she used donated funds to start the first English training school for nurses, which opened in 1860.

Formal training brought about what was later termed a "transformation" in nursing, with the new trained nurse characterized by "her neat uniform, her eternal vigilance concerning neatness, order and cleanliness, and her methodical system of work."

Nightingale was British, but her work impacted —and was appreciated by— people around the world. Her paper "Life or Death in India" was read at the Meeting of the National Association for Social Science in Norwich, 1873 and a few years later Chambers's Encyclopaedia called it "one of the most remarkable public papers ever penned."[1] In the 1880s many American girls were required to memorize and recite a Longfellow poem written in honor of Nightingale:

Nightingale's name became synonymous with kind, dutiful nursing. Clara Barton, the Civil War nurse who founded the American Red Cross, was called "The American Florence Nightingale", and she shared one of Nightingale's nicknames, "The Angel of the Battlefield".

Nightingale's training school for nurses in London inspired similar institutions in the U.S. In 1873 the New England Hospital in Boston gave the first official nursing diploma earned by an American to a Miss Richards, and Belleview Hospital in New York opened a training school the same year. By 1883 there were seventeen training schools for nurses in the United States, and applicants were examined for physical stamina as well as intelligence. Students accepted to these nursing schools received their board and lodging free of expense, and after a initial trial period (one to three months, depending on the school) had been completed they received a regular salary as well. In most schools this salary increased as the student progressed in school. The fact that nursing students were paid, whereas studying to become a doctor was (and still is) a very expensive undertaking accounted for much larger numbers of women studying to be nurses than to become doctors. Besides her salary, free room and board, any student who fell ill during her two years of nursing school was given free health care. All these things added up to make the occupation a tempting one: by 1894 the U.S. had nearly two hundred schools for nurses.

After her schooling was completed, a trained nurse could "command her own price, and that price will depend upon the wealth and liberality of her patrons, and the ability which she brings to bear on the case in hand. Good nursing is very often more important than good doctoring, and thousands of people are willing to pay liberally for such exceptional help."

Some have defended the reputations of women whose caregiving were self-taught and who therefore align more appropriately with what might be termed "pre-Nightingale" nursing. One example is Mary Seacole, who ran a 'British hotel' at Balaclava during the Crimean War. Historian A.N. Wilson described the situation in the following terms, "Miss Nightingale's hospital was where you were taken if you were wounded or fell sick. Mary Seacole was on hand for the troops in the long months when nothing appeared to be happening and … she showed courage under fire."[2] Even when lacking in formal training, traditional nurses like Seacole could still embody the same devotion to care which characterized Nightingale. Perhaps the best words to use in association with Seacole would be gumption and grit. In her memoir she described her own determination to help those on the front: "Let what might happen, to the Crimea I would go. If in no other way, then I would upon my own responsibility and at my own cost." Her 1881 obituary in The Englishwoman's Review recalled her heroism during the war, reporting, "She was present at many battles, and at the risk of her life often conveyed the wounded off the field."

In certain circles controversy has arisen over recognition of figures like Seacole. Those who like their history one-sided and simple seem to feel that the only way to laud Seacole involves demonizing Nightingale, and naturally Nightingale's defenders take issue with this. Personally, I like to think history is big enough to recognize all its heroines.

Since the nurse in my series was to be a caregiver and complement to Silas Hayes, a cantankerous hypochondriac, she had to be a match for him in pure cussedness and also provide a commensurate level of comic relief. Following the tropes of various serialized nineteenth-century fiction (and the likely socioeconomic origins of a woman who went into nursing school) indicated a character with a fairly strong ethnic background. My first thought was that she might be Irish, but Gabriel and I both felt that this was a little too much of a cliché, and he was the one who suggested Appalachian. (Fans of A Rapping At the Door will remember that McCoy did have an Irish mentor, Matron O'Reilly.)

Choosing her name allowed for a double in-joke. "McCoy" is an homage to the historic family of the same name, although Nurse McCoy is from a different part of Appalachia and would deny kinship with them or any part in their infamous feud with the Hatfields. Shortly after choosing the name for this reason, I realized it could also be considered a fun reference to another fictional healer: Dr. McCoy, from Gene Roddenbury's Star Trek.

As to what Hettie herself would think of this long, drawn-out explanation of her origins, she'd probably tell me to stop jawing and get supper on the table. After all, she's a nurse, not a historian.

Images of Nurses

Florence Nightingale:

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/COPY_1_11_34_1866-e1402062188591.jpg

Mary Seacole:

http://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/news/20141121/mary-seacole-0

The photos of anonymous nurses in the slideshow above were scanned from our private collection. To see more detailed versions, go to www.thisvictorianlife.com/photos-of-nurses.html

[1] "Nightingale, Florence." Chambers's Encyclopaedia. Volume V. New York: Colier, 1890. p. 599.

[2] Wilson, The Victorians. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 2003, p. 178.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed