Modern minds often view the term "romantic" as synonymous with "frivolous", but for the Victorians nothing could have been further from the case. The wives of those gallant men doubtless adored their sumptuous homes, but the gifts had a very practical side as well. The home was considered woman's sphere, and it was natural that the property should be in her name. More importantly, in the late nineteenth-century, when a man gave property to his wife it became completely protected by law from confiscation to cover the man's own debts.

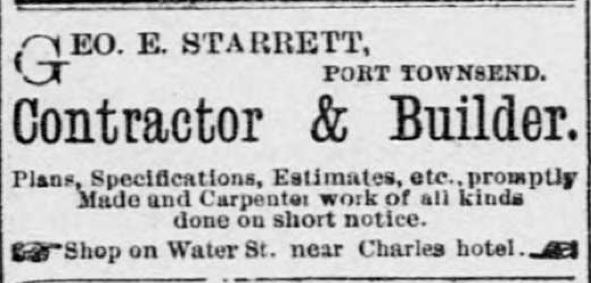

The men who commissioned architectural masterpieces like the Ann Starrett Mansion and then gave them to their wives knew exactly what they were doing. A business man does not become wealthy enough to have such a house built without substantial financial acumen. Of course he (and his wife) would take advantage of any means at their disposal to protect their property.

In earlier times, the the marriage laws of most places held the property of married couples in common between the husband and wife: legally, they were considered to be a single unit. This goes all the way back to Old Testament ideas about marriage being a case of two becoming one. The property was historically recorded under the husband's name because it had to be under someone's name, and in any sort of functional marriage where husband and wife work as a team, the question of whose name was attached to documents seemed largely a pedantic one.

In the early Victorian era critics screamed that this system was subject to abuse and left women vulnerable. What about dysfunctional marriages where the husband and wife didn't work as a team—was it really fair to have everything in the husband's name? In his novel Man and Wife writer Wilkie Collins (the John Grisham of the Victorian era) imagined the following poignant scene between the police and an abused woman whose furniture had been sold to pay her drunken husband's debts. (The novel was published in 1870 but the scene was set a number of years earlier):

[Abused woman]: "I have bought the furniture with my own money, sir... It's mine, honestly come by, with bill and receipt to prove it. They are taking it away from me by force, to sell it against my will. Don't tell me that's the law. This [is] a Christian country. It can't be.'

"'My good creature, says [the policeman], 'you are a married woman. The law doesn't allow a married woman to call anything her own—unless she has previously (with a lawyer's help) made a bargain to that effect with her husband before marrying him. You have made no bargain..."[1]

Situations like these led to changes in marriage and divorce laws that separated the property of husbands and wives, permitting a married woman to hold assets and rendering those assets legally inviolate from any debts her husband might incur.

It didn't take long for canny couples to exploit an obvious loophole in the new law. Gail Hamilton explained it succinctly in her 1872 (non-fiction) piece, Woman's Worth and Worthlessness:

"It seemed an unjust and degrading thing for a married woman not to be allowed to hold property independent of her husband, and one state after another changed its laws to enable her to do so; but testimony goes to show that the principal practical use made of the law, thus far, has been to enable the husband to put his property into the hands of his wife, and thus live on the enjoyment of it, and do business on the strength of it, without having it liable for his debts or subject to the risks of his business."[2]

Clever couples would place major assets (like those beautiful mansions of the late 1880s and 1890s) in the wife's name—a gift from her husband. He was then free to gamble with whatever financial investments seemed likely to yield returns. If he lost all his personal assets (which high-stakes business investors often do), whatever had been placed in his wife's name was still safe and sound: his creditors couldn't touch his wife's assets, no matter how deep his debts were.

Hamilton went on to describe examples of how the new law could result in human suffering just as reprehensible as the old law: "[I]n New York a married woman holds, independent of her husband's control, thirty thousand dollars. This money she received from him when he was in good business and in full health. He became paralyzed; and she at once took a paramour and sailed to Europe, leaving her husband an annuity of three hundred dollars, and supporting her paramour out of the proceeds of the fortune which her husband had given her."[3]

A good description of the property rights of married women in America appeared in a late-nineteenth-century popular manual for women:

"With reference to Statutes or Court decisions presenting or defining any of the distinctions between men and women in the management of affairs, those of the State of New York will be taken as a guide in whatever may be said here. The reason for this is…the fact that so many of the States recently created have either adopted it as a whole or accepted it as a model…No perceptible change is effected by marriage in the property rights of a woman living under any of the codes modelled upon that of New York. Her control of all that was her own remains the same during her life, and any right passing to her husband at her death is limited by the questions of children or no children, as well as by any last will and testament which she may leave behind her.

She, on the other hand, acquires no right in his personal property beyond her right to be supported, sometimes pretty widely interpreted with reference to debts of her contracting… In his real estate she acquires a "right of dower," the only visible effect of which, during his his life, she will discover to be the necessity he is under of obtaining her signature, jointly with his own, to any deed or other instrument affecting the ownership of his landed estate. She cannot be compelled by him to sign any such paper. It must be done with her free will and consent, and she must say that it is so in a written affidavit, or the paper is defective and the title does not pass away, so far as her rights are concerned, whatever may become of his own…

In accepting what is sometimes called a "partner for life" a woman does not of necessity become his business partner. He may become bankrupt without harm to her estate."[4]

This new legal arrangement actually put more control into the wife's hands than the husband's: he had no control over her assets after marriage, but he did need her permission to do anything with his own! Most importantly: he could lose every penny he owned and his bankruptcy would not affect her holdings.

In England the situation was similar:

"[W]ith reference to all property accruing to the wife since 1882, it is hers, without the intervention or legal participation of her husband, to do with as she thinks fit, her rights and liabilities with reference to such property being the same as if she were not married. And, with reference to wives married later than 1882, their marriage makes no difference to their rights and liabilities respecting property accruing to them either before or after marriage.

Under the modern law, a husband is liable for debts incurred by his wife for necessities, whether he assent to the purchases or not, unless she be otherwise fully provided, and he has notified the creditor before purchase that he will not be answerable. Such notification is worthless, however, if it be proved that the husband has not fully provided his wife with necessaries equal to her rank and his means. On the contrary, a wife is not liable for any debt incurred by her husband, unless she joins in giving the order or initiating the business in such a manner as to commit her separately from the obligation.

A husband is liable for the maintanence of his wife's children born before the marriage, but a wife is not liable for the maintenance of her husband's children born before the marriage."[5]

There is a point here worth repeating: a husband was liable for his wife's debts, but she was not liable for his. A husband's property was subject to confiscation by his creditors, while his wife's was not. This extraordinary protection for women's property under the law is exactly what led to numerous assets being transferred to wives throughout the English-speaking world during the 1880s and '90s.

Whatever one's opinion about the new state of affairs, it was a cozy financial shelter for the happily married.[6] Mr. and Mrs. P.T. Barnum and Mr. and Mrs. L. Frank Baum all took advantage of the dodge—and saved themselves considerable hardship when major investments failed in the husbands' names.

Of course, any system is subject to abuse. As Gail Hamilton put it,

"Under the best and wisest laws individuals may suffer. No law can be framed which shall completely shield man or woman from the consequences of ignorance, incapacity, or folly. You can place the control of property, the rights of contract, with husband or wife, or both, and it will still remain that, if a woman marry a brutal, coarse, selfish or lazy man, she will suffer for it, in mind, body and estate; if a man marry a frivolous, inprincipled, uneducated woman, she will drag him down. No change in laws can affect the fact that in marriage the character of the parties is of the first importance, and the settlement of their property is but subordinate. If they are wise and good, they are more likely to be happy than if they are foolish and selfish."[7]

Many modern commentators have ridiculous ideas about Victorian property laws being unfair to women, and especially wives. However, the actual historical record shows a different story. The realities of history are far more complex and nuanced than people have often been led to believe, but it is by examining the original records that we find the truth.

[1] Collins, Wilkie. Man and Wife, New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, Publisher, n.d., p. 280.

[2] Hamilton, Gail. Woman's Worth and Worthlessness, New York: Harper & Brothers, pp. 250-251.

[3]Hamilton, ibid.

[4] The Woman's Book, Volume I, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1894. pp. 81—82:

[5] Beeton, Isabella. The Book of Household Management, London: Ward, Lock & Bowden, 1893, pp. 1637—1638.

[6] Fans of the movie "The Shawshank Redemption" might remember how the protagonist—an imprisoned accountant—won his guard's favor by coaching him through a similar dodge to avoid taxes.

[7] Hamilton, Gail. Woman's Worth and Worthlessness, New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 253.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed