""[I]t takes so much courage to stand up for one's principles, one's ideas."

"But why do it? Why not accept what everybody says is so, and go along comfortably?"

"Why not? I often ask myself. But — well, I can't."" — Graham Phillips David. A Woman Ventures. 1902, pp. 216-217.

This world is not a place which readily accepts difference. Some days it's hard to even get out of bed in the morning, let alone leave the house. But I do. I do it because I refuse to let the idiots win, because I refuse to let ignorant strangers dictate how I live my life. And I do it to show others that it is possible to live out one's dreams, to not be crushed by the pressure of conformity. I never claimed it was easy: nothing worthwhile ever is. But the reward is self respect.

Reporters often ask me what the most difficult part of my life is. They are invariably surprised when I tell them—without hesitation—that it is dealing with other people's reactions. The journalists seem to be expecting some plaintive lament about dealing with Victorian technology, but those are the joys of my life. The hardships come from daily dealings with the ignorant.

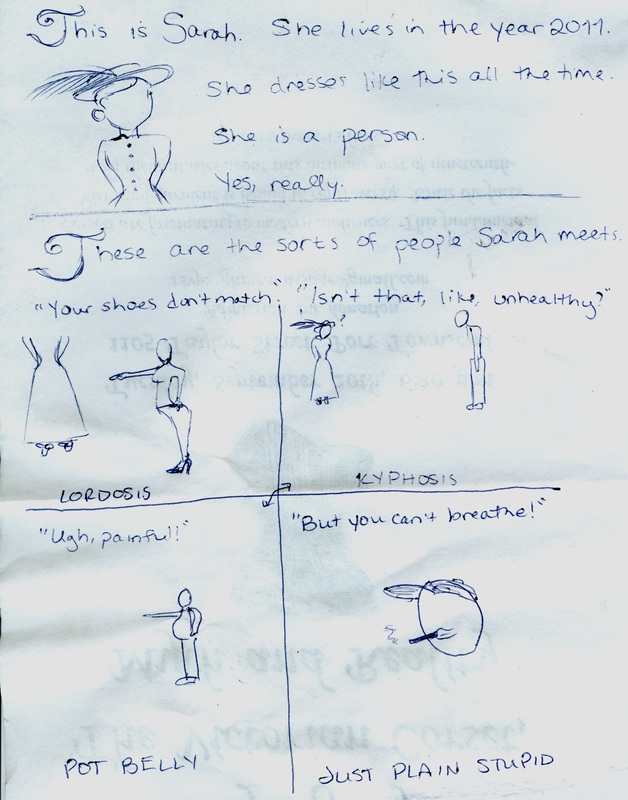

A few years ago after witnessing just a few of the things I deal with on a constant basis, one of my friends drew a comic for me illustrating just a few small bits of the hypocrisy I deal with from critics every day.

It takes a great deal of willpower to feign deafness when people hiss at me that I'm a freak, or worse. My husband and I wanted so badly to live in Port Townsend that he gave up a job at the Library of Congress so we could move here; and yet we've received hate mail telling us to get out of town and repeating the word "kill... kill... kill..." over and over again.

Words aren't the worst of it. The worst are the total strangers who come up and try to paw and grope me—and then start screaming to whoever will listen that I need to be punished when I refuse to let them.

Just as bad are the people who side with them, who say that anyone who looks or acts differently from the rest of the world "deserves" to be treated as less than a human being and that they're "asking for it," that the groper's behavior is "only natural." Those are the situations that make me want to just crawl into my closet and never leave it. But if I did that—if everyone did that—then evil would win.

"Keep your hands to yourself" is one of the earliest lessons parents teach their children. In terms of importance for functioning in society, it's on a level with "Don't steal things that don't belong to you" and "Don't poop on the floor." Most children master these basic rules of human interaction long before they enter kindergarten. (If their parents have been negligent their teachers will certainly drill the ideas into them.) Kids are actually really good at behaving themselves. It's adults who seem to think rules of decency don't apply to them.

Gabriel and I took his Victory bicycle and my trike to Sequim this weekend for the lavender festival. We'd been wanting to do this for years; even before we had high wheels we wanted to ride around to the different farms on our safety bikes. But July is the height of the busy season at the bike shop where Gabriel works, and he could never get time off during the festival. He had to put in a request more than a year in advance to get a day off for it this year. After all that wishing, all that planning, we just wanted what any couple on a special day trip wants. We wanted to have a good time together.

No one should ever have to plan security issues when out for a day with their lover, but we've sadly learned how necessary this is. I hate how planning out logistics of self-protection has become such a quotidian part of any outing.

"If we can find something to back up against when we stop," I told Gabriel as we discussed the matter. "—Then we can use that, the Ordinary and the trike to make three sides of a triangle. That would give me a fence I can stand inside while we eat the lunch we're bringing. Like we did last time we went to a public event." I shook my head in disgust. "I shouldn't have to think about these sorts of things."

"I know," Gabriel sighed and stroked my hand. "I wish we didn't have to. Let's just try to have a good time, okay? We've wanted to do this for so long."

I wanted to go early, partly for cooler morning temperatures and partly to avoid the worst of the crowds. There seems to be a critical mass of population that yields bad behavior. Some bullies are a combination of coward and exhibitionist: they won't move unless the presence of a crowd puffs up their bravado. Some people will behave badly whether there are witnesses present or not, but simple statistics mean that a large crowd of people contains more of these than a smaller grouping would.

I just wanted to see the flowers.

We got up early and trucked our highwheels out to Sequim after a quick breakfast. (Even in the 1880s, it was already common to move bikes and trikes around via other forms of transportation.) We rode our cycles out to the furthest farm on our itinerary, Jardin du Soleil, and arrived there at 8 a.m. The well-groomed fields were full of row upon row of fragrant lavender being worked by thousands of honeybees, but the land was virtually empty of humans. I honestly considered this a fairly ideal situation. The farm's owner told us they wouldn't open until 10, but grudgingly allowed that we could go in early since we had cycled all the way out there already.

It didn't last long.

The second farm was called Purple Haze, and was much closer to town. By the time we arrived, quite a few people were already there. The day had heated up rapidly: it was nearly eighty degrees and we'd been pedalling along in full sun. Gabriel proposed we look for somewhere in the shade to eat our sandwiches.

We found a shady spot under some conifers on a slight incline. We were wilting a bit from the heat of the day and our sweaty ride, and the cooler temperature of the spot was a welcome relief. But I was worried as I looked at the trees' trunks. They were widely spaced, and wouldn't provide much of a wall. I glanced at Gabriel, who was also frowning.

"I can't lean the Ordinary against that," he said, indicating massive wads of sap oozing from the nearest tree trunk.

"Lean it against the trike's driving wheel," I suggested. It wouldn't create the full triangle fence we'd made before with the high wheels, but at least it was something.

Gabriel shook his head. "I don't want to damage the spokes. Here—" He walked over to some nearby white pickets in the sun and leaned his Ordinary against them. I looked at him in concern. "It'll be alright," he told me. I looked over at the Victory, then back at my husband. "I'm right here," he assured me. He stood at one end of the trike, himself making the barrier that his bike would have been. I stood behind the trike's large driving wheel, as close as I could to the tree trunk without leaning on the gobs of sap. I looked in concern at the gap between the tree and one of the trike's steering wheels—a gap through which a determined idiot could pass, if they really tried.

And I hated, hated, hated that I had to think of such things on a beautiful day when I just wanted to see flowers with my husband. No one should have to game out fences to protect themselves, ever. Especially not in America, the country we call "The Land of the Free."

Lavender is a sun-lover, so the shady trees were set apart from the fields. At first this meant that there were few people lingering by them, but high wheels attract interest and soon people were coming over to see our cycles. Giving free, impromptu history lessons is a natural consequence of using Victorian technology, and it's fun to open people's eyes to the past—as long as they're respectful.

I used to enjoy these opportunities for outreach, these chances to open people's minds about another time, another culture. But these days it's so stressful to go out in public that I have to force myself to do it, just to prove I can. Too many gropers, too many perverts, too many hands grasping at my waist, my private body, my rump while they scream that I must be wearing a bustle because an ass as big as mine can't possibly be real. (No, I don't wear a bustle. That's my own body they're grabbing, calling too big to be real. Even if I were wearing padding, their behavior would be no less horrific.) There have been too many. A single one would have been too many. Memories of all these groping, violating encounters stalk my mind and conspire to steal the joy of outings from me.

And yet, I refuse to spiral downwards into despair. That would be letting them steal my joy. That would be letting them win. I know there are nice people in the world, who really are interested in learning about ways people can be different, instead of just attacking that difference or using it as an excuse to treat them as less than human. There are kind people, good people in the world, and it would be wrong to let the assholes make me lock myself away from the kind ones.

Behind the semi-shield of my trike's high driving wheel, I took our sandwiches and canteen out of my basket. I let Gabriel handle most of the questions while I ate; he's better at talking to strangers than I am. In our tight partnership I'm the writer, he's the talker. I used to be better at talking, but I've had to get so damn wary of strangers who approach me. I never know what they're going to try.

Several dozen people clustered around, intrigued by the high wheels. Gabriel talked with them about the history of cycling, the ways technology has changed over the years, and ways in which some aspects of the cycling industry are far older than people realize. Teaching people about these things is exactly what we enjoy doing. After a while I started to chime in with bits of history as I found my voice. As the crowds grew, I wondered if some of them were coming in to the farm especially to see us as word spread.

An older gentleman who was particularly intrigued sat down near us and we chatted companionably. He was sweet, and interested, and asked very intelligent questions. Answering his queries practically served the teaching function of a Socratic dialogue for the benefit of the audience drawn to the high wheels. I started to enjoy myself. This was exactly what I wanted from the day.

Then a woman tried to lift up my skirt.

She actually climbed around the trike to get to me then reached down, grabbing at my short cycling skirt.

I slapped her hand away. "Keep your hands to yourself!" My heart raced, flooded with adrenaline. Who is this woman, that she thinks she can just come up and start pawing a stranger? On what planet is that okay?

She responded with a shocked look, offended that I would dare prevent the liberties she was trying to take with me. "I just wanted to see what you felt like."

What sort of an idiotic statement is that?! Through my rage, the wit that keeps me sane chirped, I want to see what the seat of Hugh Jackman's trousers feels like, but I wouldn't go pawing him! I kept this to myself. I merely told the woman, "'Keep your hands to yourself' is something we're supposed to learn when we're children. You're old enough to know better." She was in her late fifties.

"I just wanted to see if it was real!" She yelled in an affronted tone.

Ye gods! What sort of an excuse was that supposed to be? Imagine someone on trial for assault telling that to a judge! "You should be ashamed of yourself," I told her in a low tone.

She left then, screaming insults at me.

I swallowed the lump of rage in my throat, then gave shuddering sigh, relieved she was gone. I leaned against Gabriel.

The nice old man we'd been talking to looked at me sympathetically. "I'm sorry," he said.

I set my jaw. "You didn't do it." You've only been sweet to us. You're not the one who should be apologizing. But I know I'll never get an apology from people who can't behave themselves to begin with.

He looked surprised at my comment. "I know, but... I'm just sorry it happened."

I set my trike at a more acute angle, trying to make a better fence of it. "Happens all the time." I said grimly.

"People think they can just come up and grab us like we're a museum exhibit," Gabriel explained angrily. "—Except that you can't even do that in museum exhibits!"

The old man smiled and shook his head. "No, you sure can't!" He looked over in the direction the woman had gone. "What was wrong with her, anyways? Thinking she could just come up and grab someone?"

A large part of me wanted to leave the farm right then, to get out of the place where danger had appeared. But I tried to focus on all the nice people we had talked to before this incident, on the nice old man who was still there, who wanted to make up for something that wasn't even his fault, or his place to fix. I told myself that one person wasn't representative of the whole, and to not let one bad incident chase us off.

A few minutes later, the situation got even worse.

Someone who works for the farm marched up to me, an angry look on his face. He looked at the huge crowd of people gathered around us, pointed at me, then pointed at a distant, isolated spot. "Come over here, I want to talk to you!" He ordered.

After what had happened, there was no way I was leaving my tricycle fence, or Gabriel. "You can talk to me here," I told the man firmly.

He hesitated a brief moment, casting a concerned glance at all the witnesses present since I refused to let him isolate me. Then he glared at me darkly again and continued. "You just grabbed a woman!"

"I told her to keep her hands to herself when she tried to lift up my skirt!"

"She told me she just wanted to feel you."

What the hell? No wonder this guy didn't want witnesses. "She had no business trying to paw at me!"

The old man behind me spoke up in my support. "I saw the whole thing. This girl had every right to tell that woman to leave her alone."

The farm employee ignored him and barked at me, "You should have just let her. She's upset now."

She's upset?!!!! If I had been wearing a muslim veil, or if Gabriel had been wearing a yarmulke, would this man have told us we should just let people grope those as well? Or if Nicole Kidman had been there and someone "just wanted to feel" her breasts, would this cretin have encouraged that as well? The sad and infuriating thing is that he probably would have.

It was bad enough that the incident had happened in the first place, but the fact that an employee of the venue—an official representative of the farm—was standing up for my assailant was beyond the pale.

"Do you want us to leave?" I asked flatly. If the farm was supporting people groping their guests, I had no desire to be there any more.

My question made the man hesitate. He looked at the large crowds which our presence had helped draw into the business. "I—uh—"

"Are you asking us to leave?" I repeated.

"I'm just saying if someone wants to feel you, you need to let them."

I turned to Gabriel. "We're leaving."

My one regret is that I didn't thank or say goodbye to the old man who had been so kind to us. I just turned by back on the farm representative who had told me I needed to let people grope me while I was there, and I left. No hesitation.

The crowds were too thick to ride my trike. As I pushed it to the exit a number of people wanted me to stop so they could take pictures, but I ignored them. I had to get out. I had to get away from this, get somewhere I could run, somewhere I could ride.

Gabriel caught up with me near the exit. A family in our path called for us to stop for a photo; Gabriel halted, I didn't. "I'm not stopping," I told him. I felt that I was being effectively kicked out for daring to stand up for the privacy of my own body. I had no intention of letting people assume in any way that I supported this business.

After we'd crossed the farm's perimeter and were on the public road, Gabriel told me softly, "Here, pull over with me. You need a hug."

He held me close, stroking my shoulder. I nestled my cheek against his soft red beard, taking comfort from his closeness.

"Are you okay?" He asked.

"No," I answered honestly.

A passing family came up to us then, wanting to ask questions about the high wheelers. I put on my best friendly face, reminding myself they had no idea of anything that had just happened and it wasn't their fault. We pretended to be cheerful and Gabriel demonstrated a mount and dismount on the Victory. Then I breathed a sigh of relief when the family left.

"What do you want to do now?" Gabriel asked gently.

"I don't want to just go home," I told him firmly, although of course part of me did. "I don't want our day to end like this."

"Neither do I," he agreed. "So, what now?"

"Let's try to find another farm to visit."

We entered onto the road again. The temperature was into the 90s on the Sequim Prairie, but despite the heat I threw everything I had into beating my treadles, pushing my 65 pound machine as fast as it would go. Gabriel let me run off steam for a bit, then he gently pointed out that we were heading quite far into the middle of nowhere.

Sweat trickled down my face and I drew a long breath of the hot prairie air. "You're right," I admitted. I wondered if I should drink some of the water from our canteen, but I really didn't feel like stopping. "Let's turn around."

The side road we'd been following was empty this far out of town; I made a U-turn without dismounting and headed back towards the city.

"When we started all this," Gabriel told me quietly as he paced me. "—I never dreamed people would act so horribly. That it would be so hard on you."

It took me a moment to respond because the tears welling up in my eyes made the road blurry. I couldn't see where I was going, and I had to pull myself together so I wouldn't crash. It was that or stop, and I didn't want to stop. When I could see again I told him, "I don't want to give up our ideals and philosophies and just try to pretend we're like everyone else. Because that's letting the idiots win. And I don't want to live my life that way."

"I agree." He sighed. "But I do wish I could make it easier for you. I love you very much."

"I love you, too." I looked over at my beloved husband and gave a wry laugh. "I want to stroke your hand but if I did that, I would crash into you. So, know that I'm mentally holding your hand."

He smiled. "Me, too."

When we neared the border of town, Gabriel asked me where I wanted to go from here.

I sighed. "Oh— I don't know." All I knew was that I didn't want to go home yet. I pulled over and stopped, not a clue where to go from here.

It takes very little poison to damage a person's system. If the poison is diluted enough though, if it's drowned in enough benevolent material, it can pass through without permanent harm. I wanted for the day to somehow have enough benevolence to drown out the poison.

After a while we saw a little blonde girl, probably four or five years old, watching us from across the street. Her mother was trying to get her to move along, but her eyes were riveted on my tricycle. This close in to town there was heavy traffic; when the fascinated girl tried crossing the street to get a better look at our cycles, her mother's eyes flooded with fear.

"Stop!"

"Stop!"

The mother and I shouted at the same time, seeing the girl's danger. I'd instictively held up my hand, palm out like a traffic guard, as I did so. "Don't come to us! I urged the girl. "We'll come to you," I promised.

Gabriel and I weaved our way through the traffic to where the girl and her mother stood safe on the sidewalk now.

Talking to the little girl and her mother was somehow comforting, calming. I'm better with kids than Gabriel is so I did the talking this time, and I enjoyed the excited look in the child's eyes, the way her face lit up as she looked at my cycle.

"Do you have a tricycle? Or a bicycle?" I asked her.

She blushed and hid shyly behind her mother, who smiled down at her. "You do, don't you?" Her mom encouraged. "Out in the garage, you know."

I smiled at the girl as she peeped out at me. She was so sweet, my smile didn't have to be entirely feigned any more. "I didn't learn to ride a bike until I was nineteen years old!" I confided. I pointed over at Gabriel. "He taught me."

He waved at the little girl.

"—And now I have a really special tricycle," I concluded. "I like it a lot."

The mom smiled at me, then glanced in the direction of the street fair associated with the lavender festival. I sensed she wanted to be moving towards their original destination, I bid told Gabriel we should probably be going. We told the girl and her mother we hoped they would have a good day, then we rode on.

I didn't want to linger at the street fair—too many crowds—but chance had brought us to the edge of it. There was a small church group sitting outside on the outskirts, and one of the women waved to us and asked if we'd like some cold water.

Cold water, and kindness. I needed both.

We pulled over, away from the crowds, by where the church people were sitting. The sweet and friendly woman told us how her friend had seen us riding up the road earlier that morning, and worried about how hard we must be working to pedal our heavy machines on such a hot day. I quickly drank all of the bottle of water she had given me then I burst into tears, overwhelmed at the abrupt change from hostility to gentleness.

Gabriel put a gentle hand on my back. "We've had a rough day," he explained to the woman.

"It's—just—so—nice to be treated kindly," I told her, fighting hard to stop my tears.

"Oh! But that's how people are supposed to treat each other! We're supposed to be nice!" She offered me a hug, and I gently embraced her shoulders.

We stayed with the church group a while, talking about our cycles and about history, then she told us just a little about their church. When we moved on she told us to take care of ourselves and to stay strong.

The poison was starting to be diluted. I still wanted to see just one more farm, though. The first farm of the day had been nice—perhaps only because it was empty, but it was nice. The second had been a disaster. I didn't want the day to end in a tie between good and evil. I wanted good to win.

Before last year's lavender festival I had read up on the various farms and had particularly wanted to see one that advertised a duck pond on their premises. My map hadn't been very good and I had gotten extremely lost while searching for the duckpond farm. I never did find it, and after hours of searching in the hot sun I'd had to give up and turn my wheels homewards.

As we left the church group this year, I asked Gabriel if we could look for the duckpond farm. Completing a quest I had failed in the previous year seemed like a way to salvage the day.

We found a map and packed the high wheels back in the truck. (Part of why I had gotten so lost last year was that Sequim is bisected by a highway that's virtually impossible to cross on a bike.) With the map's help—and even more importantly, with the help of signs which had been added since last year—we found Nelson's Duckpond and Lavender Farm. I had brought my lace parasol with me; I unfurled it now for walking around the farm.

Gabriel squeezed my hand. "What would you like to see?"

I glanced around at the pretty little farm, with its artistically curving rows of lavender. "Let's look for the ducks," I said.

The sound of running water led us to a pond with a tiny little island in its middle. A female mallard sat in the long grass there, near a set of curving jets flowing from invisible spouts.

"I think most of the ducks are probably hiding from the heat," Gabriel commented. "They're probably down in the shade of those grasses."

I nodded. "It's still really pretty here," I told him.

Diluting poison.

"What else would you like to see?"

"Well," I told Gabriel. "When we came in I saw that they're selling lavender lemonade. I think I'd like some of that."

Gabriel gave me a thumbs-up. "That's a good idea!"

We walked back around to a lemonade stand by the barn, run by two children—one inside, one outside the stand. As I bought my drink they both told me they liked my "umbrella."

"Oh—" I juggled my purse back into place. "Thank you." I tilted the parasol down so they could see the lace, the holes that would never stop rain. "When it's for the sun though, it's called a parasol." I almost went into a linguistic explanation of how "para" means against and "sol" means sun, but I decided that might be too much. I just smiled at both children, and asked the girl outside the stand if she'd like to hold it.

Her eyes went wide and a big smile crossed her face. She nodded vigorously and I handed her the parasol. She held it a few moments, twirling it and watching the play of light through the lace. She thanked me when she handed it back, and Gabriel and I retreated a short distance while I drank my cold lemonade.

I was nearly down to the ice when a man approached us. "Are you paid actors," he asked. "—To add ambience to the festival?"

I hid my involuntary wry smile behind my lemonade cup. It would be nice to be paid for being ourselves, but of course we have no reason to expect it. I'd settle for just not being kicked out on the basis of our individuality.

"No, we're not actors," I told him. "Just ourselves."

He stayed chatting for a while and I let Gabriel handle the conversation. It was a pleasant one, and when it was over I told Gabriel we could go home now. The day's balance of good over evil had shifted, the poison was diluted enough.

I bought some lavender from the farm's gift shop, and my eyes drank in the rows of waving purple blossoms near the exit as we left. I was glad that I hadn't just given in earlier, that we hadn't gone straight home when things turned sour.

I wish life were easy, but it's not. Since that is the case, the only way to get through every day is to insist on finding the good, hunting down positivity until it can drown out the negative.

It takes pressure to make a diamond. It takes fire to temper steel. And lest that steel simply melt under the heat of the forge, it takes a blacksmith to care for it. The world is a cruel place, but I have a wonderful husband who cares for me, and whom I love with all my heart. We are stronger together than either of us would be alone, and together we stay strong against the world. We keep following our dreams, whatever people say or do, and grab all the happiness we can in this world.

We hope that by following our dreams we can inspire others to follow theirs.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed