Maintaining this website (which you are enjoying for free!) takes a lot of time and resources.

Please show your support for all our hard work by telling your friends about Sarah's books —and by buying them yourself, too, of course!

Historical Article (1889)

A Woman Without Cares or Children

Advised to "Adopt An Orphan Asylum."

Olivia Lovell Wilson

Good Housekeeping, March 16, 1889, pp. 229-230

(Fiction)

Aunt Serepta had come to stay a fortnight. Here she was, sunny and smiling, her inevitable knitting bulging her pocket, and her cheery voice forestalling her niece's welcome:

"Well, here I am, Rose. I have come to stay, too, until I've finished these socks, and by that time I will have made you a jar of mince meat, finished piecing the pink quilt, and sewed on all your shoe buttons."

"Then you have come just in time, dear aunt," laughed Mrs. Silverthorn, but with a little weakness in her tone, "for I told Robert yesterday that if I did not get a chance to sew on some shoe buttons, I should have to stay at home perforce."

"Haven't lost your good servant?" inquired Aunt Serepta.

"Oh, no! Only the pressure of outside work seems to grow greater every day. You see, having no children, and such a nice little home, I naturally can assume more outside work. Every one seems to regard me in the light of a public officer. Robert says I am like Pooh-bah. But I suppose I have fewer cares than other people."

"So, necessarily, by the law of compensation, you are asked to shoulder all you can of somebody else's burden. Come, sit down, and tell me all you have been doing lately."

"It would be easier to tell you what I have not done," laughed Mrs. Silverthorn again, pointing at her work-basket, which did present a formidable aspect, "and I am sorry to say I cannot stay home with you this afternoon, for I have to attend the Woman's Auxilliary of the Mission Work. I am the secretary and treasurer, you know. You will not mind being left alone?"

"No, no. You must not mind me, or I shall not come again."

So Rose Silverthorn hastened away, while Aunt Serepta attacked the work-basket and surprised a number of garments quite incomprehensible to her, - a crocheted tidy half finished, a bureau cover, sash curtains, a lot of lace and illusion half fashioned into a cap, a package of tickets marked "to be sold before Tuesday next," and lastly, a roll of cloth which proved to contain two small pairs of boys' trowers [sic], cut and basted.

"Good land!" ejaculated Aunt Serepta, using her one forcible demand of exclamatory emotion, "what is she going to do with these? Even if she adopts a child, she couldn't get one to fit the pants very well. And she's not one to go about anything in that backward fashion, even if she should take a full-grown child, and want to provide accordin'."

She laid them aside in much perplexity, and then made up the curtains and cast the tidy aside as a frivolous and absurd delusion of a younger generation. Aunt Serepta had no more patience with a crochet needle than she had with a crimping iron, or a tennis racket. She frowned on the innocent looking hook as an insult to her clean, shining knitting needles.

When Mrs. Silverthorn returned a friend was with her, who accompanied her home to ask her to take her Sunday school class in the Mission school during a six months absence.

"You can do it so well, Rose. You have no cares like mine, and not a child to look after or worry about," said her friend conclusively.

Mrs. Silverthorn assented reluctantly, but at these last words, flushed and said nothing.

"And now, Rose, what are these?" demanded Aunt Serepta, as the friend gone, Rose sank into a chair and gazed pathetically at the little boys' trowsers Aunt Serepta brandished tragically. "Your basket seems full of other people's plunder, but these puzzle me."

"They are all right. I cut them by a pattern Mrs. Bender gave me, and she had seven - boys, I mean, not patterns."

"What do you intend to do with them? I believe they are correct in every respect, but since you do not wear them yourself, and they are too small for Bob-"

"Do not be sarcastic Aunty, it does not sit well on you. Give them to me, I must take them to old Mrs. Brown this moment. Mrs. Tremaine said I might as well cut them out, and Mrs. Bender thought I had more time to myself since I have no children, and so few cares. I'll do them right up for Mrs. Brown, and take them. She is a poor woman who needs the work."

"Wait a moment. What is this thing?" shaking the tidy.

"Oh! I am teaching Lena Morton a new stitch. She comes tonight for her lesson, and also Mr. Leigh to try over the solo for the church choir Sunday.

"And this cap?"

"Mrs. Grey worried so about it, that I have been making them for her lately. I made three last week."

"And the tickets?"

"Dear me, I must take them, and stop at Mrs. Crawford's on my way back. I must sell at least twenty before the concert. Mrs. Post, the minister's wife, asked me to sell them. She said I was so untrammeled, having no children, and always seemed so well. I will take these to Mrs. Crawford. Back in a minute!"

Aunt Serepta kept an account during that visit, and the moments she spent with Mrs. Silverthorn aggregated just two hours and twenty minutes, and her visit lengthened to three weeks.

One after another the demands poured in upon Mrs. Silverthorn, and Aunt Serepta grew so familiar with a certain terminus of a sentence in making these demands, that she grew rosy red with indignation. Now it was a church supper.

"You're just the one, Mrs. Silverthorn, to oversee the kitchen. Nothing to keep you home, no children to trouble you."

Again she was a delegate to a temperance convention, or appointed a teacher in a kinder-garten, while there was no end to the siege laid for her to attend French or German classes, join a glee club, or a coterie for intellectual development.

"You have such nice original ideas, and then, having no children, you can be so free to go and come. And you are so well and strong!

Aunt Serepta grew to glare angrily when the well-born inevitable sentence smote her ear.

Finally, the last day of Aunt Serepta's visit, Mrs. Silverthorn had a headache, and absolutely laid on the sofa without glancing at the clock anticipating an engagement.

"Tell everyone I want to be excused," she had said to the servant. But one friend, more solicitous and intimate than the others, was admitted. After condoling, she ventured to state her errand. She wanted Mrs. Silverthorn to join a class in embroidery, to be taught by a woman of limited means.

"Rose!" began Aunt Serepta, warningly, "be firm. Do not join another earthly thing!"

"But this is so delightful, and she is such a charming teacher and-"

"I really feel, Mrs. Crawford, as if I had so much to do already."

"The idea of your talking that way, Rose. You, without a child to bless yourself, and so little care of any kind. I really wonder how you fill your time."

"Well, I can tell you," struck in Aunt Serepta, clashing her knitting needles, as she waved them aloft in sudden wrathful energy. "She is doing the duty of ten women that have got children. She is teaching two Sunday school classes, a free kitchen garden, selling tickets for concerts and church fairs, hunting up poor women in the interests of flower missions, reading at the hospital, secretary and treasurer of three societies, and a member of two musical circles, putting aside the few little unnecessary things one is called upon to do for a husband, for she has no children, and an excellent servant. As it is, I wish she had seventeen, or more, children, then, perhaps, she could go to her grave in peace. As it is-"

"I am not dead yet, Aunt Serepta," laughed Mrs. Silverthorn, intensely amused at Mrs. Crawford's puzzled countenance during Aunt Serepta's recital.

"Because you inherit a strong constitution from your mother, you need not boast. But don't join an embroidery class, for I may go to my last rest before long, and then who will sew on your shoe buttons?"

After Mrs. Crawford departed, Mrs. Silverthorn lay smiling at her evident confusion, and Aunt Serepta's wrath, when that worthy lady said solemnly:

"Rose, I am going to write a book."

"Good! What will it be, a novel?"

"Yes - very novel. I shall call it 'Robert Silverthorn's Wife, or what is expected of a Woman who is Without Cares or Children.'"

"That will do very well," then, after a pause, "in how many chapters, Aunt Serepta?"

"Chapters? It will fill three volumes," replied Aunt Serepta calmly. Then as she tied on her bonnet, and wound up her knitting, she bend a still more solemn glance on Rose and said: "Do you want my advice? It is not expensive, and it may show you a loop-hole of escape to restful peace?"

"Go on."

Aunt Serepta bent over her niece and said in a low tone, "Adopt an Orphan Asylum!"

|

If you liked this article you might also enjoy these:

A Fortune Found In A Pickle Jar (Fiction—1889)

A Man in the Kitchen: The Difference Between A "Betty" And the Other Kind (1889)

An Old Maid's Paradise (1889)

Individuality and Equality (1894)

Woman's Cycle (1896)

Woman's Exchanges as Training Schools and Markets for Work (1894)

Woman's Work for Woman (1889)

In a seaport town in the late 19th-century Pacific Northwest, a group of friends find themselves drawn together —by chance, by love, and by the marvelous changes their world is undergoing. In the process, they learn that the family we choose can be just as important as the ones we're born into. Join their adventures in

The Tales of Chetzemoka

To read about the exhaustive research that goes into each book, click on their "Learn More" buttons!

The Tales of Chetzemoka

To read about the exhaustive research that goes into each book, click on their "Learn More" buttons!

Buy the book

|

First Wheel in Town:

|

Buy the book

|

Love Will Find A Wheel:

|

Buy the book

|

A Rapping At The Door:

|

Buy the book

|

Delivery Delayed:

|

***

Anthologies

|

Love's Messenger

A Choice Collection of Victorian Love Poetry The verses embraced within these pages have been kissed awake after a long slumber. Copied from the fragile pages of nineteenth-century books and magazines, they are the whispers of lovers long entranced. In this beautifully diverse collection of Victorian love poetry high-born ladies and their eloquent beaux keep company with simple maids whose sweethearts pledge their love in simpler —and often much funnier— terms. Prepare for your happy sighs to be joined by occasional giggles while you hold this book close to your heart. Compiled, edited and introduced by Sarah A. Chrisman, author of the charming Tales of Chetzemoka historical fiction series, This Victorian Life, Victorian Secrets, and others. |

|

Quotations of Quality

A Commonplace Book of Victorian Advice, Wit, and Observations on Life Eloquent statements are like the seeds of beautiful flowers: in the fertile garden of the mind they grow and blossom into inspiration, reflection, and rewarding conversations. The Victorian era was a time when people expressed themselves skillfully and beautifully, and the writings of that age are a rich legacy from the past. This little volume is a collection of sentiments on an array of subjects, among them: Books: "A minute's reading often provokes a day's thinking." —W.H. Venable, 1872. "Books are those faithful mirrors that reflect to our minds the minds of sages and heroes. A good book is the precious life-blood of a master spirit treasured up on a purpose for a life beyond." —J.F. Spaunhurst, 1896. Writing: "Every new book must have, in the consciousness of its author, a private history that, like the mysteries of romance, would if unfolded have an interest for the reader, and by unveiling the inner life of the volume show its character and tendencies." —Sarah Josepha Hale, 1866. Language: "The [Ancient] Greeks said that barbarians did not speak, they twittered." —Charles DeKay, 1898. The Sexes: "It is better for men, it is better for women, that each somewhat idealize the other." —Gail Hamilton, 1872. Love: "True love is that which ennobles the personality, fortifies the heart, and sanctifies the existence. And the being we love must not be mysterious and sphinx-like, but clear and limpid as a diamond; so that admiration and attachment may grow with knowledge." —Henry Frédéric Amiel, 1880. Optimism: "Refuse to dwell among shadows when there is so much sunshine in the world." —Hester M. Poole, 1888. History: "The past is our wisest and best instructor. In its dim and shadowy outlines we may, if we will, discern in some measure those elements of wisdom which should guide the present and secure the welfare of the future." —Frederick Douglass, 1889. Work: "Make the most of your brain and your eyes, and let no one dare tell you that you are devoting yourself to a low sphere of action." —Anonymous, late 19th-century Keep this book in a place where its wisdom can refresh your spare moments, or buy a copy for a friend to brighten their day. May the flowers of thought thus planted bear rich fruit for you. Compiled and edited by Sarah A. Chrisman, author of The Tales of Chetzemoka, This Victorian Life, and others. |

|

Words For Parting

Victorian Poetry on Death and Mourning Love and grief and the two most private, and at the same time the most universal of all human emotions. It is for love that we remember the dead: love of their spirits, love of their vibrancy, love of the good deeds which they did and which live on after them. The poems in this collection were all written by grieving hearts who have now themselves passed over into that great mystery. We can not truly know what death is, yet we know it will come to all of us. In ancient times when a friend told the philosopher Socrates that his judges had sentenced him to death he responded, "And has not Nature passed the same sentence on them?" Inasmuch as there can ever be any comfort for those left behind, part of it lies in knowing that death is a reflection of life. When it comes we cry, then we take our first faltering steps towards understanding. In time we become accustomed to this manifold enigma which nature has given us, and then ultimately we look towards the future with hope. If this little book of poems may be of some help to those in sorrow by reminding them they are not alone, then it will have done its work. Compiled and edited by Sarah A. Chrisman, author of the Tales of Chetzemoka series, This Victorian Life, and others. |

|

The Wheelman's Joy Victorian Cycling Poetry and Words About Wheels There is something inherently romantic about cycling, and there has been since the first riders set their wheels to the road. This collection of nineteenth-century poetry, prose quotes and bon-mots about cycling reflects both the ardent passion and the innocent affection cycling inspires. From the glory days of high-wheel cycling through the boom of the safety bicycle, riders were falling in love with their wheels, with new-found freedoms, and above all with each other. This delightful little collection tells of those days in their own words, and evokes sentiments which every cyclist will find timeless. Compiled edited and introduced by Sarah A. Chrisman, author of the charming Tales of Chetzemoka cycling club series, This Victorian Life, Victorian Secrets, and others. |

Victorian Secrets

|

True Ladies

|

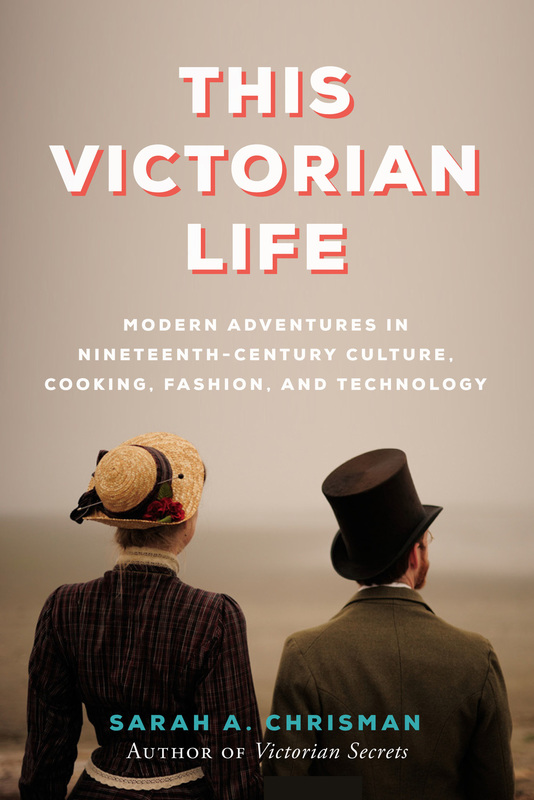

This Victorian Life

|

For words of wit and advice sage,

I hope you'll like my author page!

History lessons, folks who dare,

Please do share it while you're there!

https://www.facebook.com/ThisVictorianLife

Thank you!

***

If you enjoy our website and appreciate what we do,

please consider making a cash donation.

Everything helps, and is appreciated!

Search this website:

***