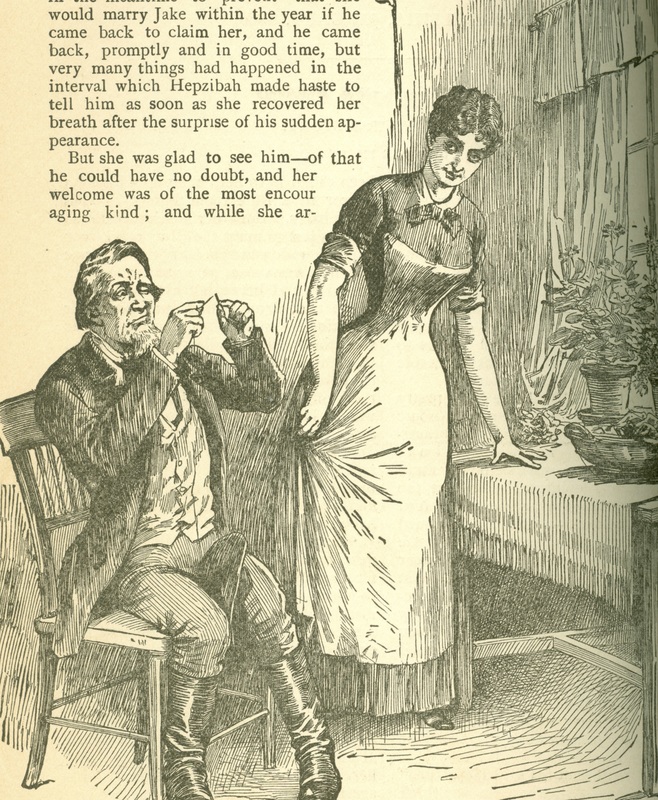

A Man in the Kitchen

The Difference Between A "Betty" and the Other Kind

By "One of the "Men Folks.""

Good Housekeeping, February 16, 1889. p. 178.

Most women heartily despise a "Betty," by which is usually meant a man who pokes his nose into the details of household affairs, dabbles in the work of the kitchen and irritates the housewife by assuming, regularly or occasionally, functions which she deems exclusive to herself. The dislike of women for this kind of man is in the main well-grounded. The average man is unfortunately unable to make himself useful in household work, without making himself, also, more or less of a nuisance. A question of this kind has, however, many sides. The women who are most jealous of their prerogatives in the kitchen are not always possessed of the best capacity for maintaining them; and some of the most perfect housekeepers the writer has ever known, easy mistresses of the arts and systems that make up the various departments of household management and industry, have been most indulgent and appreciative of the efforts of husband, son or brother to help about the house, even encouraging original experiment along the lines which have brought into being the scornful epithet above quoted. In their households the men were never spitefully ordered to "Let things alone," told to "Keep out of my way," or requested to "mind their own business," because, in the first place, the housewife respected herself too much to use such expressions or their equivalents, and because, in the second place, the men had acquired such familiarity with the ins and outs of the kitchen that they were not likely to hinder rather than help when they had occasion to turn their hand to this, that or the other matter of housework. This touches the secret of the whole matter, and a little thinking along this line will suggest a query whether women are not, generally speaking, to blame for the fact that the average man is a nuisance in the kitchen.

A mother carefully taught her sons many details of work usually considered the province of girls and concerning which boys generally grow up in utter ignorance. They washed and wiped dishes, learned to prepare plain meals, had practice in sweeping and dusting and putting to rights, and were taught to patch and darn neatly and to sew on buttons. Some of them learned something of the "higher brances." When they went out into the world they had frequent occasion to bless the mother for these useful accomplishments; and when they became heads of households, they had an intelligent practical knowledge of the details of the work of which their wives had charge and were able to make the burden easy in many ways where another man would have made it heavier.

No man worthy of the name permits his wife or any woman in his house to perform the heavy drudgery of carrying coal and wood, caring for furnaces and stoves, moving stoves or heavy furniture, beating carpets, and so on. But this need not be the limit of a man's usefulness about the house. There is no reasonable reason why a man should not be able to broil a steak, boil or bake potatoes, cook an egg, make coffee or tea and prepare other articles of food should an emergency arise to make it desirable (and such emergencies do often arise), and do it too without turning the kitchen and dining-room topsy-turvy in the operation. Some men can and do accomplish such work, and even make biscuits, griddle-cakes, and the like. A woman whose husband is in the habit of "taking hold" when needed in housework has been heard to say that she would rather have him to depend on in case of indisposition or other emergency than any girl that could be hired. He does not interfere when there is no cause for it, but he saves labor for his wife and expense for himself, and he is not at all ashamed of doing it nor afraid to undertake it. No man need be; rather any man should be ashamed of unwillingness and should regret inability to perform any ordinary household task on occasion.

Some men have or profess a horror of all housework. It is often grounded in laziness. They will go to great expense and trouble rather than turn their hands to anything in the house even to making a fire. The "Bettys" do not come from that class. Neither are they recruited from the husbands of common sense, tact and judgement, who know "how to do things" and know when to do them and when to refrain. The genuine "Betty" is a genuine meddler, whose zeal is without knowledge, whose helpfulness is without discretion and whose officiousness and conceit neutralize what might be useful in his make-up. Let her, however, accept these lines as a plea for withholding the opprobrious title from men who do not deserve it and for an honest recognition of the right usefulness of a properly taught and sensible man about the house, and even in the kitchen.

If you liked this article,

you might also enjoy these:

A Fortune Found In A Pickle Jar (Fiction—1889)

An Old Maid's Paradise (1889)

A Woman Without Cares or Children (1889)

Individuality and Equality (1894)

Woman's Cycle (1897)

Woman's Exchanges as Training Schools and Markets for Work (1894)

Women Inventors (1897)

Woman's Work for Woman (1889)

Back to Historical Articles Index

In a seaport town in the late 19th-century Pacific Northwest, a group of friends find themselves drawn together —by chance, by love, and by the marvelous changes their world is undergoing. In the process, they learn that the family we choose can be just as important as the ones we're born into. Join their adventures in

The Tales of Chetzemoka

To read about the exhaustive research that goes into each book, click on their "Learn More" buttons!

First Wheel in Town:

|

Love Will Find A Wheel:

|

A Rapping At The Door:

|

Delivery Delayed:

|

Anthologies

Love's Messenger

|

Quotations of Quality

|

The Wheelman's Joy

|

Words For Parting

|

If you enjoy our website and appreciate what we do,

please consider making a cash donation.

Everything helps, and is appreciated!

Search this website:

***