Maintaining this website (which you are enjoying for free!) takes a lot of time and resources.

Please show your support for all our hard work by telling your friends about Sarah's books —and by buying them yourself, too, of course!

Historical Article

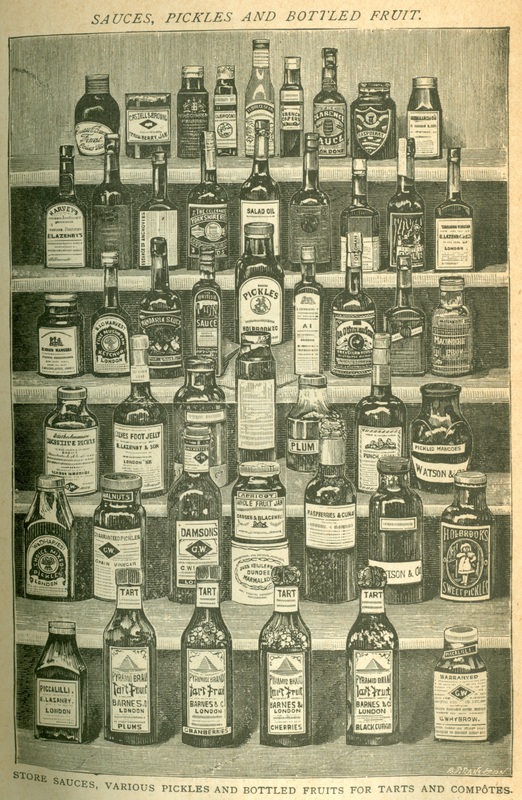

A Fortune Found in A Pickle Jar

With the Story of Its Finding

(Fiction)

By Rose Carthame

Exerpted from Good Housekeeping June 22, 1889

We held a business meeting in the dining room that evening. The round table, reduced to its lowest terms, and covered by its red Canton flannel spread, looked cheerful under the droplight. Mother Frank sat near the table with her knitting, her hands flying busily back and forth within the circle of light. The invalid was bolstered up on the shabby little lounge at the other side. The invalid was Frances. Amy was taking a surreptitious peep at her Roman History and Mab was buried in a pile of account books and paper. ("The Chancellor of the exchequer" whispered Frances to Amy.) Presently the Chancellor of the Exchequer looked up, and rapped the table three times with her pencil. "The meeting will please come to order," she commanded. Mother Frank went steadily on with her knitting, Amy shut her book with a sigh, and Frances raised herself on one elbow to command a better view of the situation. The Chancellor of the Exchequer hemmed portentously, and rose to make a speech.

"The Indians are in the habit of holding a council before they go to war," she began. "We are, so to speak, those Indians—we are at war with our circumstances. It is the noble privilege of man to triumph over circumstances, yet I cannot conceal from this assembly that circumstances are at present somewhat pressing. It is my painful duty to inform you" (here she made a harrowing pause, with her hand thrust man-fashion behind her back, and slowly refreshed herself with a glass of water.) "that a close examination of the books which our financial manager"—a bow to Frances— "handed to me this evening reveals the distressing fact that we are not making both ends meet. Meet they must and shall and lap over both ways. The question naturally arises, how shall this be done? The family treasury lies before me on the table. It contains ninety-seven cents. My next week's salary is already appropriated to certain needful articles for household use, leaving but a small margin for bonnets and gowns. What shall we do in the present emergency? I await suggestions."

There was a moment's silence as she sat down, broken only by the click of Mother Frank's needles, and then Amy pushed her hair back over her shoulders and got up. "I am not a speech maker like Queen Mab," she said with a candid little smile, "but I think it would be better to say 'What can we do?" instead of 'What shall we do?'"

"That was a very good suggestion indeed," said Mother Frank.

"But it likewise narrows the horizon," said Mab again. "When we come to count our resources, we stand something like this. I am a mere arithmetical machine by day, at so much a month."

"Mab, dear, I cannot let you speak of yourself in that way," interposed Mother Frank.

"Oh, I assure you, Stone & Chandler consider me so, and a good thing too, but considering that their hours are from eight to six the emoluments are not grand, and I am at a loss to see what more I can do in the time I have. Amy must go through school if we have to pawn all our India rubbers. Mother Frank has the care of the house on her shoulders."

"And Frances, the good-for-nothing, has to be waited on, and is of no earthly use," broke in the invalid.

"Frances, that's all nonsense. You know it is. Don't you keep our account books, do our mending, help Amy with her lessons? Don't you beat eggs, wind our worsted, arrange our flowers, stone our raisins?"

"We have so many raisins."

"The principle is the same," said Mab, grandly. "Don't you go to talk about being of no use. Now, to come down to business again, it seems necessary that something should be done. We have a house over our heads to be sure but au contraire, we have to pay the interest on the mortgage."

"Suppose you count all the possible openings," suggested Mother Frank.

"A good idea," answered Frances. "Plain sewing, machine sewing, fancy work, mending, Kensington embroidery, lustra painting (any fool could do that) wood carving."

"Oh, you soar too high," interrupted Mab. "Stenography, type-writing, law copying, lamp tending, photograph coloring, book agent, (life of President Harrison, 2 volumes) automatic nutmeg grater, proof reading, elocution, circular folding, doll's dressmaking, ladies' millinery."

"None of these things fit us," said Frances, ruefully.

Mother Frank laid down her knitting. "I can do plain sewing and mending," she said, "And I will help all I can in any way, though all my accomplishments are of the old-fashioned sort."

"No one wants any more accomplishments who can cook like you," said Frances.

"Mother Frank," began Amy, suddenly.

"What, dear?"

"I heard Emily White say yesterday that her mother was too tired to do any preserving this year, and she said she wished there was some place where she could buy home made pickles."

There was another moment of silence, and then Mother Frank looked brightly around the table. "I am not sure but Amy has hit just the very thing" she said. "I can make pickles, can't I, girls?"

"But, Mother Frank, would you go round with a distressed gentlewoman air and carry pickles for sale in a big basket?" asked Mab, amazed.

"Why no, of course not, but I think if I made a number of extra jars when I did my own preserving, I could dispose of them, perhaps, in some quiet way."

"There's a place in town where they go for such things," said Amy, eagerly. "That new Woman's Exchange over on Bank street, don't you know? You can get cake and jam and bread, and lots of things there are all home-made—but I don't know whether they have pickles or not."

"What a thing it is to be a school girl, and hear all this news" Mab remarked, coming round and pulling Amy's pig-tail, "shall I make inquiries for you tomorrow, Mother Frank?"

"If you will, dear, for it is something I know I can do."

"But won't it be too much for you, mother? Of course we will all help, but it will make you so much extra work."

"Not a bit too much. I like to fly around the kitchen very much better than I like sewing, and all that confining work."

That was one thing we all liked about Mother Frank. She always said what she liked and disliked, and treated us as if we had sense enough to understand. What we should have done with a martyr mother, who smiled, and looked patient, and never complained, I cannot imagine.

The conclave broke up after that, and while Amy strapped her books together and laid the cloth for breakfast, and Mother Frank set her muffins to rise in the kitchen, Mab gave Frances an arm up-stairs, whence smothered sounds of merriment, accompanied by a peculiar thud now and then soon announced that Mab, always in the highest spirits when the family finances were lowest, was entertaining Frances with a ballet dance on the matted floor.

Mab came home at noon next day, bristling with information. "I've been over to the Woman's Exchange," she declared, washing the "dust of the daily grind" from her hands with soap. "It's a tidy little place enough, lots of fancy work lying around, cheese cloth comfortables hung over a line like a washing day, a sort of perverted bookcase on one side with rows of canned fruit and jelly tumblers—I didn't see any pickles, Mother Frank—then there was a glass showcase full of painted china, and all the latest fads in water color paper and sachet bags, and behind it a very tony girl in the most ravishing tailor-made brown suit and a bonnet which was never made in this town, I'm positive."

"That's Queen Mab all over," said Amy, who had just come in. "When she gets to Heaven she'll look around the first thing to see how the angels are dressed."

Mab cast a withering look at her. "This lovely being was graciously civil," she went on, taking no ther notice of the audacious school girl remark, "she gave me a circular, showed me around, and told me that it was necessary to pass an examination in pickles and jams before being allowed to enter anything for sale."

"O Mab, what an idea!"

"Fact, they have a certain standard and try every new consignor's article by sample. You put your price on your goods, and they charge you ten per cent. commission on all articles sold and a subscription fee besides of one dollar."

"Oh!" said Amy, discomfited.

"Why, that is very reasonable" said Mother Frank. "Did you think they would sell things for nothing, Amy? Girls, I'll make a sample this afternoon or to-morrow, you shall all taste it, and when it is ready to send, Mab shall take it up to the Exchange."

"Our house was in one of the out-of-the-way streets and boasted quite a respectable garden at the back, where we raised a supply of fruit and vegetables, with a little outside aid from Mickey Doyle, a paid attaché of nearly all the families on the street. Amy was up bright and early next morning. Frances heard her whistling in the garden, while she picked the tomatoes, and she came in to breakfast with her cheeks as rosy as her hair ribbon. After she and Mab had gone, Mother Frank began operations in the dining room, gossiping with Frances meanwhile, and nothing more than ordinary seemed to be going on. Nevertheless, when Mab came in that night, she found the family critically tasting the mixture out of a Scotch marmalade jar. "O Mother Frank, that's going to be too good for anybody but the Norrises!" she exclaimed, when she too had seized a spoon and followed the others' example.

Mother Frank smiled in a superior manner. She had had no doubts from the first. She was quite well used to having her things turn out better than other people's.

"There is a rush of work just now," said Mab at tea. "The books are behind and I shall have to be on hand evenings for several days, but I will carry your pickles up for you some noon, Mother Frank."

"No, dear, you will do nothing of the sort" was the decided answer. "You have enough to do as it is. I will take them up myself, I am not afraid to interview your 'tony girl in brown tailor-made suit and the ravishing bonnet.'"

"It was very interesting," she declared to us on her return. "Your pretty girl in brown was not there Mab, but there were two or three young ladies showing visitors around, and the book-keeper was at the desk. I addressed my remarks to her and left a sample of that watermelon pickle you like so much, with the other. She said she could sell Chili sauce for us too, she thought there was some demand for it."

"That is, provided you get your certificate," suggested Amy, slyly.

We were not left long in suspense on that point, for Mab came in at noon two days afterwards, crying "Passed! cum laude! Girls, it was funny. I went in this noon and my girl in brown was there again, only she wasn't dressed in brown this time, but in blue, she is Miss Blake, girls, and lives in one of those lovely new houses on Hopeland Avenue. I've quite lost my heart to her. Well, she said the pickles were perfectly satisfactory, then she laughed, and the book-keeper came up, and siad that some of the young ladies had stayed down to lunch the day before, it was such a busy day, and that they had eaten every bit of your pickle up, and just raved over it. Those were her very words. She gave me back the jars. So now your career is open to you, Mother Frank, go on in the path of duty and fortune play upon your prosperous helm."

"Rather a mixed metaphor, isn't it?" asked Mother Frank smiling, but we could see that she was well pleased. On the strength of this, although it was what Mab called "Frugal Friday," we had escalloped oysters for tea.

Next morning, Mother Frank set regularly to work. Frances did some of the easiest parts and Amy was chief errand runner all the morning. When at last the bottles were filled and sealed with a resinous brown wax, they looked very tempting and Amy volunteered to carry them up herself, but we all laughed at her, and after she had lifted the heavy basket once, she was glad to surrender it to Mickey Doyle. Whent he first pay day came, Mother Frank walked in triumphantly, and turned her purse upside down upon the table. Quite a little shower of silver rolled out. "There!" said she, "it was empty before, let me see, there was a dozen tomato at 30 cents each, that is $3.24 less the commission, a dozen larger bottles at 50 cents, makes $5.40, and $2 for Chili sauce is—total $9.64—yes, that's right, for I paid the subscription fee. There is only one bottle left unsold, and they want a supply of Chili sauce on hand all the time."

"Three cheers for the Champion Pickle Maker!" said the irrepressible Mab.

"But what shall we do when all the garden things are used up?" inquired Amy, curiously.

"Oh, she will have to sow pickles, like the late Mrs. Null," said Frances. "What did you see up at the Exchange to-day, in the way of fancy work, Mother Frank?"

"They are beginning to show Christmas work, so soon. I saw some exquisite drawn work this afternoon. There was one linen scarf, the middle covered with long stitch embroidery, only twelve dollars, well, but really, it was cheap for that. Then there were quantities of aprons and blotting books, and handkerchief cases. I saw one funny thing this afternoon. The cake counter stands at the farther end of the room, and every loaf is ticketed. A woman came in for a loaf of walnut cake, and made a great face because the tag was stuck on with a pin, and she finally went away without buying it."

"Did she think it was poisoned?"

"No, but she seemed to think it might be stuck full of pins."

"Mother Frank, why don't you branch off into cake when the pickle season is over? Your Marquise cake for instance."

"One step at a time," replied Mother Frank oracularly.

And now, what more remains to be said? This year, Mother Frank is working on a more extended scale, and she has as many orders as she can fill. The pickle jar has brought a very modest fortune indeed, yet still good fortune to the Norris family, and I, Frances, who have leisure to do what the more useful members of it have no time for, have been deputed to tell our little story.

***

If you liked this article you might also enjoy:

A Man in the Kitchen: The Difference Between A "Betty" And the Other Kind (1889)

An Old Maid's Paradise (1889)

A Woman Without Cares or Children (1889)

Individuality and Equality (1894)

Woman's Exchanges as Training Schools and Markets for Work (1894)

Women Inventors (1897)

Woman's Work for Woman (1889)

***

Back to Historical Articles Index

***

In a seaport town in the late 19th-century Pacific Northwest, a group of friends find themselves drawn together —by chance, by love, and by the marvelous changes their world is undergoing. In the process, they learn that the family we choose can be just as important as the ones we're born into. Join their adventures in

The Tales of Chetzemoka

To read about the exhaustive research that goes into each book, click on their "Learn More" buttons!

Buy the book

|

First Wheel in Town:

|

Buy the book

|

Love Will Find A Wheel:

|

Buy the book

|

A Rapping At The Door:

|

Buy the book

|

Delivery Delayed:

|

***

Anthologies

Quotations of Quality

|

Love's Messenger

|

Words For Parting

|

The Wheelman's Joy

|

Victorian

|

True Ladies

|

This

|

If you enjoy our website and appreciate what we do,

please consider making a cash donation.

Everything helps, and is appreciated!

Search this website:

***