Note: All images on this page were scanned from our private archive and are the property of This Victorian Life. Image use policy: Private individuals, personal use: Include a link to this website <www.ThisVictorianLife.com> when you re-post or share any pictures from our website, and you may do so free of charge.

Commercial use or publication of images: Please contact us about fees for commercial use and high-resolution images

Victorian Values

Etiquette

Etiquette Between Husbands and Wives

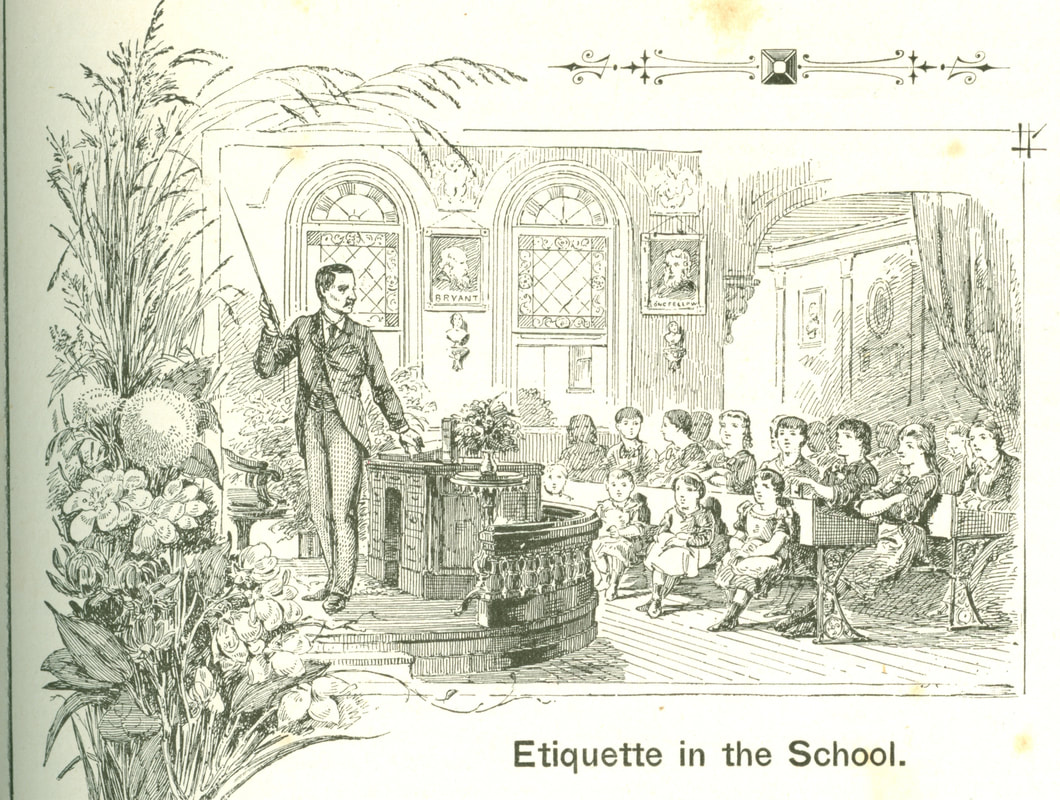

Classroom etiquette

Etiquette of Shopping

Etiquette of the Table

Butter's Right To Independence From Crumbs: A Declaration of Appetite

What Millenial Women Can Learn From Victorian Ladies

Relations Between the Sexes

She Gets All the Assets, He Gets All the Debt: The Surprising Truth About Victorian Property Laws

Etiquette Between Husbands and Wives

Equality of the Sexes

Education

Everyday Life As A Learning Experience

Classroom etiquette

Educational worksheets

***

Etiquette

Etiquette Between Husbands and Wives, 1891

Hill, Thomas E. Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms... Chicago: HIll Standard Book Co., 1891. page 167

Let the rebuke be preceded by a kiss.

***

Do not require a request to be repeated.

***

Never should both be angry at the same time.

***

Never neglect the other, for all the world beside.

***

Let each strive to always accomodate the other.

***

Let the angry word be answered only with a kiss.

***

Bestow your warmest sympathies in each other's trials.

***

Make your criticism in the most loving manner possible.

***

Make no display of the sacrifices you make for each other.

***

Never make a remark calculated to bring ridicule upon the other.

***

Never deceive; confidence, once lost, can never be wholly regained.

***

Always use the most gentle and loving words when addressing each other.

***

Let each study what pleasures can be bestowed upon the other during the day.

***

Always leave home with a tender goodbye and loving words. They may be the last.

***

Consult and advise together in all that comes within the experience and sphere of individuality.

***

Never reproach the other for an error which was done with a good motive and with the best judgement at the time.

Quotations of Quality

|

Classroom etiquette

From Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms, Thomas E. Hill, 1891, pages 173-174.

"The following are the requisites for successful management in the schoolroom:

The teacher must be a good judge of human nature. If so, his knowledge will teach him that no two children are born with precisely the same organization. This difference in mentality will make one child a natural linguist, another will naturally excel in mathematics, another will exhibit a fondness for drawing, and another for philosophy. Understanding and observing this, he will, without anger or impatience, assist the backward student, and will direct the more forward, ever addressing each child in the most respectful manner.

As few rules as possible should be made, and the object and necessity for the rule should be fully explained to the school by the teacher. When a rule has been made obedience to it should be enforced. Firmness, united with gentleness, is one of the most important qualifications which a teacher can possess.

Everything should be in order and the exercises of the day should be carried forward according to an arranged programme. The rooms should be swept, the fires built and the first and second bells rung with exact punctuality. In the same manner each recitation should come at an appointed time throughout the school hours.

The programme of exercises should be so varied as to give each pupil a variety of bodily and mental exercise. Thus, music, recreation, study, recitation, declamation, etc., should be so varied as to develop all the child’s powers. Not only should boys and girls store their minds with knowledge, but they should be trained in the best methods of writing and speaking, whereby they may be able to impart the knowledge which they possess.

The teacher should require the strictest order and neatness upon the part of all the students. Clean hands, clean face and neatly combed hair should characterize every pupil, while a mat in the doorway should remind every boy and girl of the necessity of entering the schoolroom with clean hands and shoes. Habits of neatness and order thus formed will go with the pupils through life.

At least a portion of each day should be set apart by the teacher in which to impart to the pupils a knowledge of etiquette. Students should be trained to enter the room quietly, to always close without noise the door through which they pass, to make introductions gracefully, to bow with ease and dignity, to shake hands properly, to address others courteously, to make a polite reply when spoken to, to sit and stand gracefully, to do the right thing in the right place, and thus, upon all occasions, to appear to advantage.

All the furnishings of the schoolroom should be such as to inspire the holiest, loftiest, and noblest ambition in the child. A schoolroom should be handsomely decorated. The aquarium, the trailing vine, the blossom and the specimens of natural history should adorn the teacher’s desk and the windows, while handsome pictures should embellish the walls. In short, the pupils should be surrounded with such an array of beauty as will constantly inspire them to higher and nobler achievements.

Boys and girls should be taught that which they will use when they become men and women. In the first place they will talk more than they will do anything else. By every means possible they should be trained to be correct, easy, fluent and pleasant speakers; and next to this they should be trained to be ready writers. To be this, they should be schooled in penmanship, punctuation, capitilization, composition and the writing of every description of forms, from the note of invitation to an agreement, from the epistle to a friend to the promissary note, from the letter of introduction to the report of a meeting.

Above all, the teacher should be thoroughly imbued with the importance of inculcating in the mind of the student a knowledge of general principles. Thus, in the study of geography, the pupil should be taught that the earth is spherical in form; that its outer surface is divided into land and water; that the land is divided into certain grand sections, peopled with different races of human beings who exhibit special characteristics. That civilization is the result of certain causes, and progress in the human race arises from the inevitable law of nature that everything goes from the lower steadily toward the higher. A study of the causes which make difference in climate, difference in animals, difference in intellectual and moral developments among the races - a general study of causes thus will make such an impression upon the child’s mind as will never be effaced; while the simple study of facts such as load the mind with names of bays, islands, rivers, etc., is the crowding of the memory with that which is likely in time to be nearly all forgotten.

Thus, in the study of history, dates will be forgotten, while the outlines of the rise and fall of kingdoms, and the causes which produced the same, if rightly impressed by the teacher, will be ever stored in the mind of the pupil.

So should the teacher instruct the student in every branch of study, remembering that facts are liable to be forgotten, but fundamental principles and causes, well understood, will be forever remembered."

It's obvious to everyone in the Chetzemoka cycling club that Lizzie and Isaac could make each other very happy —but really, does anyone follow their friends' hints when it comes to affairs of the heart? A prim schoolmarm and a stoic steamship captain are hardly the people to discuss their sentiments, in spite of all that everyone else does to bring them together. Love seems so easy for other couples, yet for these two the smallest challenges loom as huge obstacles. Just when progress finally seems possible, a well-intentioned little girl steps in with the kind of help they'd be better off without. Will the situation be resolved before it's too late, or will Isaac ship out for good?Delivery Delayed

|

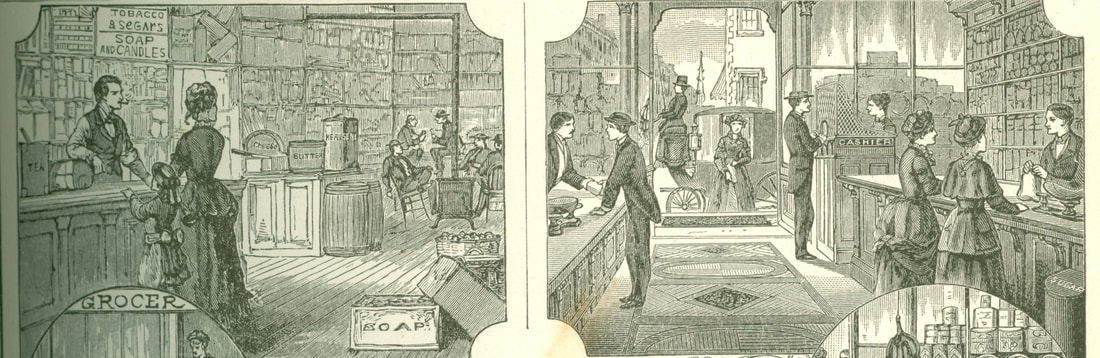

Etiquette of Shopping

Etiquette of Shopping (1891)

Do not take hold of a piece of goods which another is examining. Wait until it is replaced upon the counter before you take it up.

***

Injuring goods when handling, pushing aside other persons, hanging upon the counter, whispering, loud talk and laughter, when in a store, are all evidence of ill-breeding.

***

Never attempt to "beat down" prices when shopping. If the price does not suit, go elsewhere. The just and upright merchant will have but one price for his goods, and he will strictly adhere to it.

***

It is an insult to a clerk or merchant to suggest to a customer about to purchase that may buy cheaper or better elsewhere. It is also rude to give your opinion, unasked, about the goods that another is purchasing.

***

Never expect a clerk to leave another customer to wait on you; and, when attending upon you, do not cause him to wait while you visit with another. When the purchases are made let them be sent to your home, and thus avoid loading yourself with bundles.

***

Treat clerks, when shopping, respectfully, and give them no more trouble than is necessary. Ask for what is wanted, explicitly, and if you wish to make examination with a view to future purchase, say so. Be perfectly frank. There is no necessity in practicing deceit.

***

The rule should be to pay for goods when you buy them. If, however, you are trusted by the merchant, you should be very particular to pay your indebtedness when you agree to. By doing as you promise, you acquire good habits of promptitude, and at the same time establish credit and make reputation among those with whom you deal.

***

It is rude in the extreme to find fault and to make sneering remarks about goods. To draw unfavorable comparisons between the goods and those found at other stores does no good, and shows want of deference and respect to those who are waiting on you. Politely state that the goods are not what you want, and, while you may buy, you prefer to look further.

The above list originally appeared in the 19th-century book, Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms and was republished in Sarah's etiquette guide, True Ladies and Proper Gentlemen.

|

Etiquette of the Table

Etiquette of the Table (1891)

Rules to be Observed

Sit upright, neither too close nor too far away from the table.

Open and spread upon your lap or breast a napkin, if one is provided—otherwise a handkerchief.

Do not be in haste; compose yourself; put your mind into a pleasant condition, and resolve to eat slowly.

Keep the hands from the table until your time comes to be served.

It is rude to take knife and fork in hand and commence drumming on the table while you are waiting.

Taking ample time in eating will give you better health, greater wealth, longer life and more happiness. These are what we may obtain by eating slowly in a pleasant frame of mind, thoroughly masticating the food.Errors to be Avoided

Never eat very fast.

Never fill the mouth very full.

Never open your mouth when chewing.

Never make noise with the mouth or throat.

Never attempt to talk with the mouth full.

Never attempt to leave the table with food in the mouth.

Never soil the table-cloth if it is possible to avoid it.

Never carry away fruits and confectionary from the table.

Never encourage a dog or cat to play with you at the table.

Never use anything but a fork or spoon in feeding yourself.

Never explain at the table why certain foods do not agree with you.

Never introduce disgusting or unpleasant topics for conversation.

Never pick your teeth or put your hand in your mouth while eating.

Never cut bread; always break it, spreading with butter each piece as you eat it.

Never use your own knife when cutting butter.

Always use a knife assigned to that purpose.

Never wipe your fingers on the table-cloth, nor clean them in your mouth. Use the napkin.

Never, when serving others, overload the plate nor force upon them delicacies which they decline.

Never allow the conversation at the table to drift into anything but chit-chat; the consideration of deep and abstruse principles will impair digestion.

Never permit yourself to engage in a heated argument at the table.

Neither should you use gestures, nor illustrations made with a knife or fork upon the table-cloth.

-- Originally published in Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms, re-published in True Ladies and Proper Gentlemen.

Butter's Right To Independence From Crumbs: A Declaration of Appetite

By Sarah A. Chrisman

When in the course of holiday events it becomes necessary to form a more perfect union among families by establishing peace and ensuring domestic tranquility, a just consideration for the fallibility of mankind requires some etiquette:

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that bread-crumbs, mashed potatoes, bits of cooked vegetables, and other things on a dinner plate all have a briefer shelf-life than butter. That introducing these foreign matters into butter will, therefore, cause it to spoil before its time. Furthermore, that many people are displeased, or outright disgusted, to find the communal butter on the family table besmirched with matter from every plate.

Nor is such besmirching an inevitable state of affairs. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.

That butter should be treated like every other food upon the table. It should have its own serving utensil. Just as the dish of mashed potatoes in the center of the table has its own spoon, so, too, should the butter have its own knife. Diners should use this knife to convey a portion of the butter to their plate, not their food, then use their own knife to spread it on whatever they choose. It is for this express purpose that each place at a table is provided with its own butter knife. It would be a breach of manners to take up one's individual spoon and commence eating directly from the family bowl of mashed potatoes; so, too, is it a breach of etiquette to use the communal butter knife on one's own bread.

To secure the pursuit of happiness at the dinner table, such basic manners are instituted among families. For the support of these manners, and to ensure BUTTER'S RIGHT TO INDEPENDENCE FROM CRUMBS, we mutually pledge our attention, our care, and our holiday appetites.

When the delivery of a mysterious letter to Silas Hayes' mansion is followed by the arrival of a beautiful young woman who claims she can communicate with the dead, Nurse McCoy sniffs trouble in the wind. It's obvious to her that the newcomer is after Silas' fortune, but he is helplessly in awe of the medium's eerily intimate knowledge of his past and her seemingly supernatural abilities. Meanwhile, Kitty Brown's yearning to reach out to the departed spirit of her first love is making her push away her new husband, just when she needs him the most. The whole situation is a dreadful mess, and McCoy's got to straighten it all out before Silas' nephew and his bride come back from their honeymoon. Honestly, she doesn't know how any of the fools in this world would get along without her…A Rapping At The Door

|

Relations Between the Sexes

She Gets All the Assets, He Gets All the Debt: The Surprising Truth About Victorian Property Laws

By Sarah A. Chrisman

In researching Victorian mansions, a common theme emerges: Craigdarroch Castle in Victoria B.C., the Ann Starrett Mansion here in Port Townsend, and many other architectural masterpieces were built, not for the rich men who commissioned them, but as gifts for their beloved wives. Such histories have always struck me as deeply romantic ones.

Modern minds often view the term "romantic" as synonymous with "frivolous", but for the Victorians nothing could have been further from the case. The wives of those gallant men doubtless adored their sumptuous homes, but the gifts had a very practical side as well. The home was considered woman's sphere, and it was natural that the property should be in her name. More importantly, in the late nineteenth-century, when a man gave property to his wife it became completely protected by law from confiscation to cover the man's own debts.

The men who commissioned architectural masterpieces like the Ann Starrett Mansion and then gave them to their wives knew exactly what they were doing. A business man does not become wealthy enough to have such a house built without substantial financial acumen. Of course he (and his wife) would take advantage of any means at their disposal to protect their property.

In earlier times, the the marriage laws of most places held the property of married couples in common between the husband and wife: legally, they were considered to be a single unit. This goes all the way back to Old Testament ideas about marriage being a case of two becoming one. The property was historically recorded under the husband's name because it had to be under someone's name, and in any sort of functional marriage where husband and wife work as a team, the question of whose name was attached to documents seemed largely a pedantic one.

In the early Victorian era critics screamed that this system was subject to abuse and left women vulnerable. What about dysfunctional marriages where the husband and wife didn't work as a team—was it really fair to have everything in the husband's name? In his novel Man and Wife writer Wilkie Collins (the John Grisham of the Victorian era) imagined the following poignant scene between the police and an abused woman whose furniture had been sold to pay her drunken husband's debts. (The novel was published in 1870 but the scene was set a number of years earlier):

[Abused woman]: "I have bought the furniture with my own money, sir... It's mine, honestly come by, with bill and receipt to prove it. They are taking it away from me by force, to sell it against my will. Don't tell me that's the law. This [is] a Christian country. It can't be.'

"'My good creature, says [the policeman], 'you are a married woman. The law doesn't allow a married woman to call anything her own—unless she has previously (with a lawyer's help) made a bargain to that effect with her husband before marrying him. You have made no bargain..."[1]

Situations like these led to changes in marriage and divorce laws that separated the property of husbands and wives, permitting a married woman to hold assets and rendering those assets legally inviolate from any debts her husband might incur.

It didn't take long for canny couples to exploit an obvious loophole in the new law. Gail Hamilton explained it succinctly in her 1872 (non-fiction) piece, Woman's Worth and Worthlessness:

"It seemed an unjust and degrading thing for a married woman not to be allowed to hold property independent of her husband, and one state after another changed its laws to enable her to do so; but testimony goes to show that the principal practical use made of the law, thus far, has been to enable the husband to put his property into the hands of his wife, and thus live on the enjoyment of it, and do business on the strength of it, without having it liable for his debts or subject to the risks of his business."[2]

Clever couples would place major assets (like those beautiful mansions of the late 1880s and 1890s) in the wife's name—a gift from her husband. He was then free to gamble with whatever financial investments seemed likely to yield returns. If he lost all his personal assets (which high-stakes business investors often do), whatever had been placed in his wife's name was still safe and sound: his creditors couldn't touch his wife's assets, no matter how deep his debts were.

Hamilton went on to describe examples of how the new law could result in human suffering just as reprehensible as the old law: "[I]n New York a married woman holds, independent of her husband's control, thirty thousand dollars. This money she received from him when he was in good business and in full health. He became paralyzed; and she at once took a paramour and sailed to Europe, leaving her husband an annuity of three hundred dollars, and supporting her paramour out of the proceeds of the fortune which her husband had given her."[3]

A good description of the property rights of married women in America appeared in a late-nineteenth-century popular manual for women:

"With reference to Statutes or Court decisions presenting or defining any of the distinctions between men and women in the management of affairs, those of the State of New York will be taken as a guide in whatever may be said here. The reason for this is…the fact that so many of the States recently created have either adopted it as a whole or accepted it as a model…No perceptible change is effected by marriage in the property rights of a woman living under any of the codes modelled upon that of New York. Her control of all that was her own remains the same during her life, and any right passing to her husband at her death is limited by the questions of children or no children, as well as by any last will and testament which she may leave behind her.

She, on the other hand, acquires no right in his personal property beyond her right to be supported, sometimes pretty widely interpreted with reference to debts of her contracting… In his real estate she acquires a "right of dower," the only visible effect of which, during his his life, she will discover to be the necessity he is under of obtaining her signature, jointly with his own, to any deed or other instrument affecting the ownership of his landed estate. She cannot be compelled by him to sign any such paper. It must be done with her free will and consent, and she must say that it is so in a written affidavit, or the paper is defective and the title does not pass away, so far as her rights are concerned, whatever may become of his own…

In accepting what is sometimes called a "partner for life" a woman does not of necessity become his business partner. He may become bankrupt without harm to her estate."[4]

This new legal arrangement actually put more control into the wife's hands than the husband's: he had no control over her assets after marriage, but he did need her permission to do anything with his own! Most importantly: he could lose every penny he owned and his bankruptcy would not affect her holdings.

In England the situation was similar:

"[W]ith reference to all property accruing to the wife since 1882, it is hers, without the intervention or legal participation of her husband, to do with as she thinks fit, her rights and liabilities with reference to such property being the same as if she were not married. And, with reference to wives married later than 1882, their marriage makes no difference to their rights and liabilities respecting property accruing to them either before or after marriage.

Under the modern law, a husband is liable for debts incurred by his wife for necessities, whether he assent to the purchases or not, unless she be otherwise fully provided, and he has notified the creditor before purchase that he will not be answerable. Such notification is worthless, however, if it be proved that the husband has not fully provided his wife with necessaries equal to her rank and his means. On the contrary, a wife is not liable for any debt incurred by her husband, unless she joins in giving the order or initiating the business in such a manner as to commit her separately from the obligation.

A husband is liable for the maintanence of his wife's children born before the marriage, but a wife is not liable for the maintenance of her husband's children born before the marriage."[5]

There is a point here worth repeating: a husband was liable for his wife's debts, but she was not liable for his. A husband's property was subject to confiscation by his creditors, while his wife's was not. This extraordinary protection for women's property under the law is exactly what led to numerous assets being transferred to wives throughout the English-speaking world during the 1880s and '90s.

Whatever one's opinion about the new state of affairs, it was a cozy financial shelter for the happily married.[6] Mr. and Mrs. P.T. Barnum and Mr. and Mrs. L. Frank Baum all took advantage of the dodge—and saved themselves considerable hardship when major investments failed in the husbands' names.

Of course, any system is subject to abuse. As Gail Hamilton put it,

"Under the best and wisest laws individuals may suffer. No law can be framed which shall completely shield man or woman from the consequences of ignorance, incapacity, or folly. You can place the control of property, the rights of contract, with husband or wife, or both, and it will still remain that, if a woman marry a brutal, coarse, selfish or lazy man, she will suffer for it, in mind, body and estate; if a man marry a frivolous, inprincipled, uneducated woman, she will drag him down. No change in laws can affect the fact that in marriage the character of the parties is of the first importance, and the settlement of their property is but subordinate. If they are wise and good, they are more likely to be happy than if they are foolish and selfish."[7]

Many modern commentators have ridiculous ideas about Victorian property laws being unfair to women, and especially wives. However, the actual historical record shows a different story. The realities of history are far more complex and nuanced than people have often been led to believe, but it is by examining the original records that we find the truth.

[1] Collins, Wilkie. Man and Wife, New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, Publisher, n.d., p. 280.

[2] Hamilton, Gail. Woman's Worth and Worthlessness, New York: Harper & Brothers, pp. 250-251.

[3]Hamilton, ibid.

[4] The Woman's Book, Volume I, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1894. pp. 81—82:

[5] Beeton, Isabella. The Book of Household Management, London: Ward, Lock & Bowden, 1893, pp. 1637—1638.

[6] Fans of the movie "The Shawshank Redemption" might remember how the protagonist—an imprisoned accountant—won his guard's favor by coaching him through a similar dodge to avoid taxes.

[7] Hamilton, Gail. Woman's Worth and Worthlessness, New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 253.

Etiquette Between Husbands and Wives, 1891

Hill, Thomas E. Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms... Chicago: HIll Standard Book Co., 1891. page 167

Let the rebuke be preceded by a kiss.

***

Do not require a request to be repeated.

***

Never should both be angry at the same time.

***

Never neglect the other, for all the world beside.

***

Let each strive to always accomodate the other.

***

Let the angry word be answered only with a kiss.

***

Bestow your warmest sympathies in each other's trials.

***

Make your criticism in the most loving manner possible.

***

Make no display of the sacrifices you make for each other.

***

Never make a remark calculated to bring ridicule upon the other.

***

Never deceive; confidence, once lost, can never be wholly regained.

***

Always use the most gentle and loving words when addressing each other.

***

Let each study what pleasures can be bestowed upon the other during the day.

***

Always leave home with a tender goodbye and loving words. They may be the last.

***

Consult and advise together in all that comes within the experience and sphere of individuality.

***

Never reproach the other for an error which was done with a good motive and with the best judgement at the time.

This 1891 etiquette for husbands and wives is reprinted in Sarah's Victorian etiquette guide, True Ladies and Proper Gentlemen, available on Amazon!

|

Equality of the Sexes

Excerpted from "The Education of Women"

Abbott, Lyman. The Woman’s Book Volume 1. Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1894. pp. 341-342.

"... What is meant by the phrase "equality of the sexes?" For that matter, what is meant by the term equality as applied to persons? The phrase is constantly used, as such phrases often are, without any clear apprehension of any meaning. Is the poet equal to the man of action? or the statesman to the soldier? or the farmer to the lawyer? It is like asking, Is oxygen equal to hydrogen in the air? In the one case each is equally necessary to the constitution of the air; in the other each is equally necessary to the constitution of society. But neither is able to take the place of the other. Is the eye equal to the ear? Not when you are listening to an orchestra. For you close the eyes that you may hear the better. Are the husband and wife equal? In nursing the infant he is not equal to her; in fighting the savage she is not equal to him; and which is the more important service depends upon circumstances. The phrase "equality of the sexes" has two intelligible meanings, and only two. It may mean that men and women are equally entitled to liberty and the best conceivable development. That equality, I affirm. It may mean that their respective services in society are equally essential to its well-being, and equally divine. That equality I affirm. But it cannot mean that their services are, or their development is, to be the same. That is not to affirm equality of character, but identity of function and education, and that is a totally different affirmation. Life is often, and fitly, compared to a battle-field. Men and women are engaged in a campaign. If it were an actual campaign, with a visible foe in the field, the men would learn the manual of arms and go to the front to do the fighting, and the women would take lessons of the doctors and do the nursing in the hospitals. Some men might nurse better than some women, and some women might fight better than some men. And if it became necessary for the latter to handle a musket, no one would deny them the right; on the contrary, everyone would admire their heroism. But on the whole, Joan of Arc is not the type of womanhood. The world would not be bettered by turning General Grant into a hospital nurse, or Clara Barton into a major-general...

The reader must... remember that it is not possible to lay down any general laws according to which all women should be educated. For every individual is different from every other individual, and every life is different from every other life; therefore every education must be different from every other education."

***