Our Antique Clothing Collection

Welcome to our virtual museum! This is our private collection of antique clothing and accessories, which we use for historical presentations and community outreach. There are a few replica pieces (such as Sarah's corsets, which she wears every day; any replica pieces are noted as such), but for the most part these are authentic antiques. Enjoy!

Remember to tell your friends about Sarah's books!

Buying these books is the best way to show your support for what we do and help us keep doing it!

Antique corsets

Black cotton corset, circa 1880s or 1890s

This much-worn piece, with its many tears and repairs, is a wonderful example of how thoroughly used these quotidian items were. Most corsets were simply worn until they wore out completely.

This much-worn piece, with its many tears and repairs, is a wonderful example of how thoroughly used these quotidian items were. Most corsets were simply worn until they wore out completely.

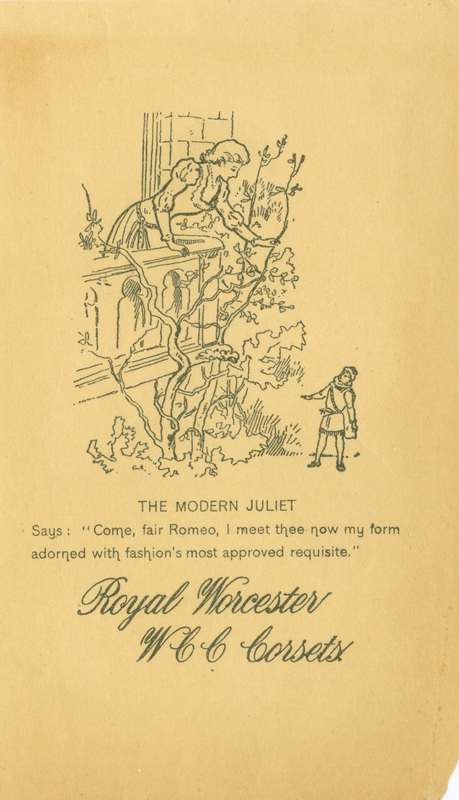

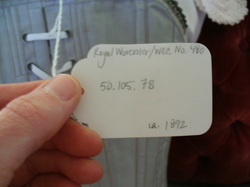

Royal Worcester corset, 1892 (Museum de-accession)

One of the old Royal Worcester factories is still standing in Worcester, Massachusetts. Here's an article about a class who toured it: http://www.telegram.com/article/20120314/news/103149868

and here's the factory's Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Worcester-Corset-Company-Factory/108146352543905

To learn more about corsets, check out Sarah's book,

Victorian Secrets: What A Corset Taught Me About the Past, the Present, and Myself!

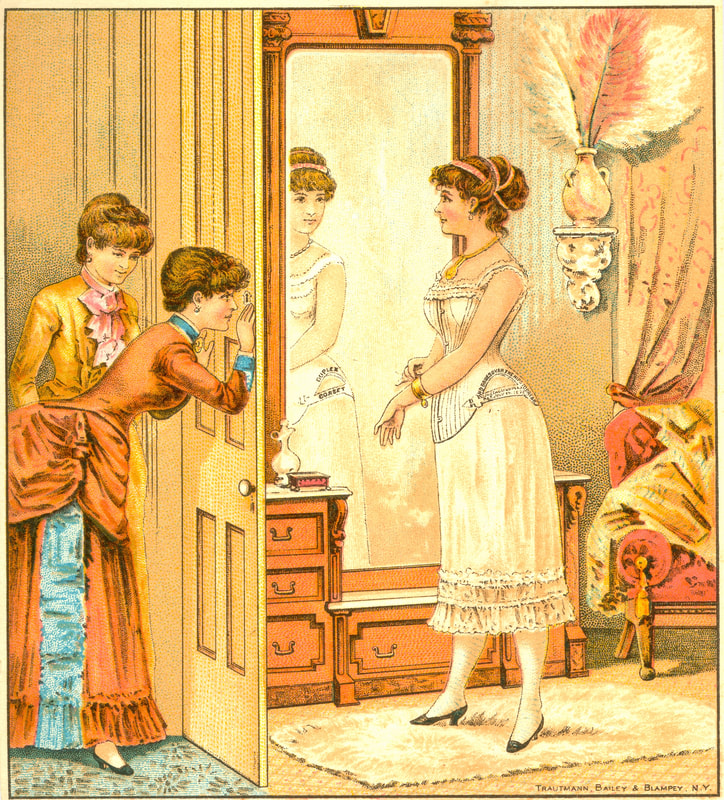

Victorian Corset Images

Corset Covers and Pantalets

(Photo at left courtesy of Sue Lean)

A corset cover somewhat resembles a modern chemise, the main difference being that the corset cover will nearly always have some sort of tie to pull it flat against the body, especially at the waist. They were generally constructed of cotton, often with hand-made lace forming the the shoulder straps, and served two main functions. The first of these was entirely pragmatic: the corset cover protected the delicate material of the bodice from snagging or tearing upon the metal clasps of the corset. The second function of the corset cover was more aesthetic in nature: it softened the lines of the corset. Late nineteenth-century bodices were drawn up as tightly as possible to the body in order to show off a woman's figure, but for the metal boning of a woman's corset to show through the bodice itself was considered vulgar in the extreme. (The modern equivalent of this attitude can be seen in countless twentieth and twenty-first century mothers hissing at their teenage daughters, "Your bra-strap is showing!" Or, in a more extreme case, an incident of particular vividness in my own experience when one of my former professors made the interesting fashion choice of pairing a scarlet bra with a sheer silk blouse, and the female students in the course were still talking about it weeks afterwards.) The material of a corset cover is very thin, but it is just sufficient to blur the hard lines of the corset boning under the bodice, giving a softer, more feminine look to the outfit.

The garment known to modern women as underpants, or "panties," did not exist in the Victorian era. Under their petticoats, women wore pantalets, light shorts typically made of cotton lawn (alternatively, they were sometimes constructed of linen or silk.) Pantalets, or "split bloomers" as they would later be called, were split right down the middle, leaving the crotch area open and allowing women to urinate standing upright, just like their male counterparts. The arrangement was extremely convenient, for it allowed women to use sanitary facilities of any kind without removing any garments whatsoever. (Anyone who has spent time waiting in line in a modern ladies' restroom can attest to the inconvenient delay caused to modern women by the necessity of fumbling through layers of panties, trousers, and pantyhose, dragging each one successively to the ground before relief can finally be obtained. In my own humble opinion, womankind took a massive step backwards when gave up this magnificently practical garment.)

Our collection includes several corset covers, and likewise several pairs of pantalets. Some are sturdy cotton broadcloth, meant to be practical and long-lasting. My favorite pantelets are shown here: dating from the 1870's, they are made of cotton lawn (a filmy, light-weight material that feels a bit like wearing a cloud), and decorated with hand-made lace. The original silk bows shattered, as Victorian silk often does. I retained the fragments, but the bows shown here are modern replacements.

A corset cover somewhat resembles a modern chemise, the main difference being that the corset cover will nearly always have some sort of tie to pull it flat against the body, especially at the waist. They were generally constructed of cotton, often with hand-made lace forming the the shoulder straps, and served two main functions. The first of these was entirely pragmatic: the corset cover protected the delicate material of the bodice from snagging or tearing upon the metal clasps of the corset. The second function of the corset cover was more aesthetic in nature: it softened the lines of the corset. Late nineteenth-century bodices were drawn up as tightly as possible to the body in order to show off a woman's figure, but for the metal boning of a woman's corset to show through the bodice itself was considered vulgar in the extreme. (The modern equivalent of this attitude can be seen in countless twentieth and twenty-first century mothers hissing at their teenage daughters, "Your bra-strap is showing!" Or, in a more extreme case, an incident of particular vividness in my own experience when one of my former professors made the interesting fashion choice of pairing a scarlet bra with a sheer silk blouse, and the female students in the course were still talking about it weeks afterwards.) The material of a corset cover is very thin, but it is just sufficient to blur the hard lines of the corset boning under the bodice, giving a softer, more feminine look to the outfit.

The garment known to modern women as underpants, or "panties," did not exist in the Victorian era. Under their petticoats, women wore pantalets, light shorts typically made of cotton lawn (alternatively, they were sometimes constructed of linen or silk.) Pantalets, or "split bloomers" as they would later be called, were split right down the middle, leaving the crotch area open and allowing women to urinate standing upright, just like their male counterparts. The arrangement was extremely convenient, for it allowed women to use sanitary facilities of any kind without removing any garments whatsoever. (Anyone who has spent time waiting in line in a modern ladies' restroom can attest to the inconvenient delay caused to modern women by the necessity of fumbling through layers of panties, trousers, and pantyhose, dragging each one successively to the ground before relief can finally be obtained. In my own humble opinion, womankind took a massive step backwards when gave up this magnificently practical garment.)

Our collection includes several corset covers, and likewise several pairs of pantalets. Some are sturdy cotton broadcloth, meant to be practical and long-lasting. My favorite pantelets are shown here: dating from the 1870's, they are made of cotton lawn (a filmy, light-weight material that feels a bit like wearing a cloud), and decorated with hand-made lace. The original silk bows shattered, as Victorian silk often does. I retained the fragments, but the bows shown here are modern replacements.

(Corset covers from the 1880's.) Notice the difference in stiffness between the broadcloth corset cover on the left, and the lawn corset cover on the right. The more delicate, lawn corset cover would have added less bulk under a bodice, but the finer material was more expensive and wore out more quickly than the cheap, sturdy broadcloth. The corset cover shown on the left, therefore, was likely owned by a poorer, lower-class woman than the one on the right.

1880's Crinoline

A crinoline serves the same function as voluminous petticoats, while reducing the number of underskirts required to hold out an extremely full overskirt. It is, arguably, the least useful Victorian garment, and wearing one is a bit like walking around in a mobile bird-cage. A framework of metal wires (horsehair, in earlier versions) hangs down from straps which fasten around the wearer's waist. A padded bustle may or may not be attached to these straps over the derriere to accentuate it. The period of the 1860s to the 1880s might be considered the Victorian heyday of the crinoline, and examination of pictures from the time shows the article shifting its shape dramatically during that short life-span. It blossomed out in full, broad hoops in the 1860s, then dwindled to a narrow horse-shoe shape before disappearing altogether in the 1890s. A crinoline was always worn with at least two petticoats: those worn under the crinoline protected the wearer's legs from discomfort caused by contact with bare wires, and those worn over the crinolines softened the lines of the frame so that they did not show through the outer skirt (much in the way that a corset cover softened the lines of a corset.)

Petticoats

Petticoats (literally, "small coats," from middle English) were worn under the main skirt to fill it out, as well as to provide warmth. In cold climates, women would quite often wear quilted petticoats of cotton or wool during frigid weather. (Wearing one of these is somewhat akin in sensation to being wrapped up in a cozy blanket all day.) Finer petticoats might be made of lighter wool, cotton, or silk. These could range from the utilitarian (sturdy white cotton, although even these tended to have lace trim) to the ornate (brightly colored silk taffeta.) The 1890's, especially, saw a surge in popularity for bright, striped silk petticoats. The rustling sound these made as a woman passed by was considered to be quite alluring, but even more provocative were the bright flashes of color they showed when she lifted her skirts to ascend a staircase or mount a carriage. I consider myself quite lucky to have acquired one of these gorgeous 1890's silk petticoats (via electronic means) from an antiques dealer in England. Because it is watered-silk, it did not suffer the same chemical decay which plagues most Victorian-era silk, and is in remarkably good condition. It is a beautiful piece, and I love showing it off at presentations. (Photo below courtesy of Evelyn Greenberg)

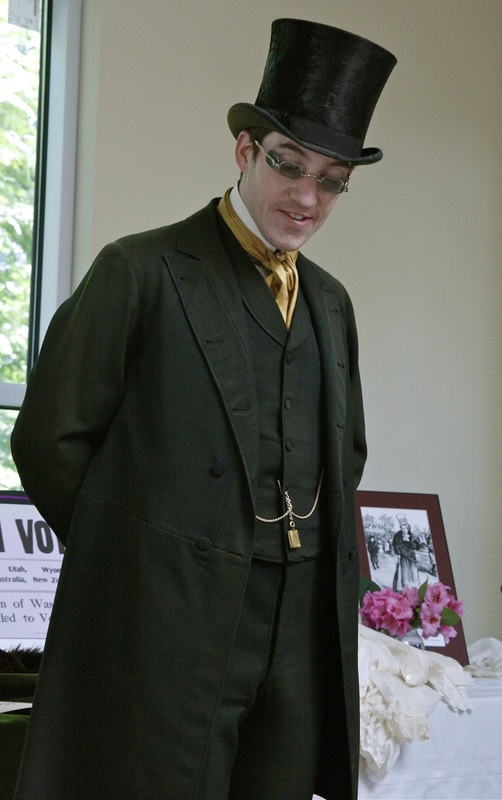

1860s Men’s Linen/Wool Frock Suit

A fairly heavyweight linen/wool blend, this green three-piece suit has a wonderful, if possibly apocryphal, provenance. The antique dealer from whom it was purchased said that it was originally owned by an itinerant preacher in Ireland in the decades following the Potato Famine. The heavy all-weather weight of the suit, as well as the characteristic blend of linen and wool, the gold silk lining decorated with shamrocks, and the excellent state of preservation incline us to lend some credence to the tale. However, certain other features indicate otherwise: preachers almost exclusively wore black (even in Ireland), and their suits typically had high collars and single breasted fastenings rather than the peaked collar and double-breasted design of this suit. Without firm evidence, it is impossible to know for sure - but it certainly is fun to study and speculate. At the very least, this story, whether true or false, has become part of the history of the suit.

1890's Plaid Skirt

Plaids were very much in fashion in the 1890s, a phenomenon which started in Britain and, like many fashions, quickly crossed the Atlantic. This skirt, made of a wool-silk blend, was originally intended to accompany a matching bodice, which was either never completed, or later partially deconstructed. The latter is the more likely possibility, as fashions in bodices could change with relative rapidity, and it was common to take apart an article which was no longer fashionable, and re-work it into something more in vogue.

1890's Tea Gown

In the Victorian era, the term "dress" technically denoted a two-piece ensemble, in which the bodice was separate from the skirt. (This allowed for greater ease in fitting, construction, and care of the garment.) A one-piece unit such as this one (shown above) would more properly be called a "gown," or a "wrapper," although admittedly there was a certain degree of laxity in the terms.

Black cotton dress, circa 1890's.

(Photo courtesy Sue Lean.)

(Photo courtesy Sue Lean.)

Summer Dress (replica of an 1870's dress, which we also own)

(Photo taken at the Freer Gallery, Washington D.C. Courtesy of Paul Kalata)

The really funny thing about this photo is that I had never seen or heard of Whistler's Arrangement in White and Black until I walked into a room at the Freer Gallery and came face-to-face with a life-sized portrait of a woman wearing my dress! (The woman in the portrait was Maud Franklin, Whistler's mistress.) She was even wearing similar shoes to mine, and a very similar hat -the main difference in the latter being that hers was brown and mine blue. I never intentionally imitate famous people; but to, by pure chance, find a portrayal of one in clothes so strikingly similar to my own was too perfect of a photo opportunity to let slip by.

This dress is a very faithful copy which I made of a Victorian summer dress which is also in our collection. The original dress dates from the 1870's; Gabriel found it through an online seller and gave it to me for Christmas last year (2009). Unfortunately, the original dress does not fit me: it is too big in the waist, and too small in the bust. Hence, my desire to make a copy. (Also, we save our real antique clothing for presentations and special events. With a replica, I'm comfortable wearing it on a daily basis. This has become my favorite hot-weather dress, and I've worn it almost every day this summer.) Both the original and the replica are made of white cotton lawn (the original has some foxing on it due to its extreme age), trimmed with white cotton eyelet. The buttons on both are mother of pearl. (I was lucky enough to find a lot of antique buttons for sale, some of which matched the original buttons exactly.)

Because of the long sleeves and long skirt, many people expect it to be hot. The truth, though, is that it is actually much cooler than a shorter garment. The thin cotton lawn is designed to let in the slightest breeze and, being an entirely natural material, is far more breathable than modern synthetics. At the same time, it provides UV protection by keeping the sun at bay. The white color reflects a certain amount of light (as opposed to colored fabrics, which absorb the heat), and the material itself acts as a physical shade.

The really funny thing about this photo is that I had never seen or heard of Whistler's Arrangement in White and Black until I walked into a room at the Freer Gallery and came face-to-face with a life-sized portrait of a woman wearing my dress! (The woman in the portrait was Maud Franklin, Whistler's mistress.) She was even wearing similar shoes to mine, and a very similar hat -the main difference in the latter being that hers was brown and mine blue. I never intentionally imitate famous people; but to, by pure chance, find a portrayal of one in clothes so strikingly similar to my own was too perfect of a photo opportunity to let slip by.

This dress is a very faithful copy which I made of a Victorian summer dress which is also in our collection. The original dress dates from the 1870's; Gabriel found it through an online seller and gave it to me for Christmas last year (2009). Unfortunately, the original dress does not fit me: it is too big in the waist, and too small in the bust. Hence, my desire to make a copy. (Also, we save our real antique clothing for presentations and special events. With a replica, I'm comfortable wearing it on a daily basis. This has become my favorite hot-weather dress, and I've worn it almost every day this summer.) Both the original and the replica are made of white cotton lawn (the original has some foxing on it due to its extreme age), trimmed with white cotton eyelet. The buttons on both are mother of pearl. (I was lucky enough to find a lot of antique buttons for sale, some of which matched the original buttons exactly.)

Because of the long sleeves and long skirt, many people expect it to be hot. The truth, though, is that it is actually much cooler than a shorter garment. The thin cotton lawn is designed to let in the slightest breeze and, being an entirely natural material, is far more breathable than modern synthetics. At the same time, it provides UV protection by keeping the sun at bay. The white color reflects a certain amount of light (as opposed to colored fabrics, which absorb the heat), and the material itself acts as a physical shade.

Sunglasses

Gabriel's fold-out sunglasses, circa 1850s

These sunglasses have four lenses -all of them green! The front two remain fixed, and the side lenses can be swung to shade the peripheral vision or to double over the front.

These sunglasses have four lenses -all of them green! The front two remain fixed, and the side lenses can be swung to shade the peripheral vision or to double over the front.

Sarah's sunglasses - blue-tinted glass, steel rims. Circa 1890s.

1880's Women’s Mourning Ensemble

This lightweight two-piece cotton dress is typical of a mourning outfit for the late Victorian period. All-black ensembles were socially required for those whose families had recently experienced a death. This custom became especially prominent during and after the Civil War, for obvious reasons. Because of the short notice required by a death, these dresses were some of the first examples of off-the-rack, ready-made clothing sold by catalogs, shops and department stores. The requirements of various stages of mourning, and the manner of indicating relationship with the mourned, were lengthy, detailed, and complex. For more on mourning, see http://www.thisvictorianlife.com/mourning-and-mourners-1888.html

Pigeon-fronted Linen Dress, circa 1905

In the early 20th century, the Victorian hourglass silhouette changed into the style known as "pouter-pigeon" -so called because of the full-chest's resemblance to a strutting pigeon. The sleeves of this dress are hand-made lace, and its detail is exquisite.

1890's Lady's Winter Dress

This dress was made in approximately 1895 by Barnard, Sumner and Putnam - a large dry-goods manufacturer and importer based in Worcester, Massachusetts. A period ad from this company claims “this store can never be the receptacle for poor, or old, or second-hand stuff, no matter how low the price. We stand by what we sell, and we request you not to keep anything that does not suit you.” Their reputation rested on guaranteed quality, and up-to-date style. Worcester was an important textile center for most of the 19th century, and this dress gives you an idea why. The main fabric of the dress is a highly textured wool with a pattern intended to hide dirt and wear, and you can see the pleated silk brocade fabric which makes up the decorative front of the bodice. This highly decorative and brightly colored fabric was probably treated with some of the newer category of industrial, chemical dyes. These additives often included heavy metals, and originally gave the fabric a heavier, more luxurious ‘hand’ and a brilliant luster, but the passage of time has given these chemicals ample time to corrode the structure of the fabric - if you look closely, you’ll see the extensive shattering that has begun. The colors remain far more intense on the inside because they have been protected from the light. Luckily, these panels are not at all structural: the bodice and the skirt are both lined with a much tougher cotton base, and this layer takes the strain of the many hooks and eyes that hold the bodice and skirt closed. The bodice lining also includes separately cased steel boning, to ensure smooth and clean lines, even over the corset. The skirt connects to the bodice through a special belt and loop system, as well as hooks and eyes, in order to keep the bodice snugly in place over the waistband. Everything is intended to contribute to creating a put-together look, even after a trip across town to visit with friends, or when out on a shopping expedition.

Belle Epoque-Era Cape

Gabriel gave this cape to Sarah as an anniversary present to celebrate their fourth year of marriage. It took her the next three years to repair it and stabilize the over 1,000 jet beads.

The main body of the cape is green wool, and it is decorated with burnt-butter colored silk-velvet, accented with jet. It dates from the 1890's, when it would have been an upper-class woman's visiting cape, worn when she paid calls on friends about town.

The main body of the cape is green wool, and it is decorated with burnt-butter colored silk-velvet, accented with jet. It dates from the 1890's, when it would have been an upper-class woman's visiting cape, worn when she paid calls on friends about town.

Gold-Rush Era Lady's Sealskin Jacket

This luxurious lady's jacket originates from Seattle of the 1890's -when the Emerald City was still a logging town, but also a major port for ships leaving for the Yukon. The same ships which transported hundreds of men and supplies to the gold-promising wilderness returned laden with other arctic treasures, not least of which were the furs. This jacket was probably originally sold at Nordstrom's -Seattle's first department store.

(Photo courtesy of Sue Lean)

1890's Lady's Hat /Bonnet

This charming little head-piece could be considered a hat or a bonnet, according to its placement on the head. As a hat, it sits forward on the crown of a lady's head; as a bonnet, it rests on her bun. The silk-velvet is accented with cockerel feathers and an ostrich plume, and it ties under the chin with silk ribbons.

Hat Pins, circa 1890 -1910

Hat pins were used to anchor a lady's elaborate hat to her hair: the long pin would stab through the body of the hat and slide into the hair (preferably intersecting a hairpin, to add stability). The silver-colored pin on the left is typical of the Gibson-Girl style hat-pins of the 1910's, while the other two hat-pins are older and topped with jet.

(Photo Courtesy of Evelyn Greenberg)

Man's tuxedo (antique) and Lady's Silk Ball Gown (replica)

Note the antique tango comb (circa 1910) in Sarah's hair. This piece is typical of elaborate hair combs that upper class women wore when they went dancing (hence the name).

Man's cape (circa 1890's)

Double-tiered cotton cape, probably originally part of an overcoat.

Man's Frock Coat (circa 1910)

Wool frock coat with flared skirts

Man's Everyday Shirt (circa 1900's)

Cotton shirt with silk stripes

Lady's Beaver-fur Winter Accessories (1890's)

These three items are a matched set: winter hat (left), muff, and tippet. The tippet would have been worn around the neck like a scarf, to keep a young woman warm in frigid winter weather.

Clothes-brush

Used to remove lint and dust from clothing, this clothes-brush has natural boar bristles and celluloid accenting (circa 1890)

Lady's boots

It is extremely rare to find surviving nineteenth-century footwear, but this pair of lady's boots from the 1890's is a lovely example. They are too small for my feet, so during presentations I display them and wear a similar, replica pair.

Nineteenth-century boots were far sturdier than their modern equivalents. This sturdiness had a (quite literal) price. Made by hand by skilled tradesmen, boots were one of the most expensive items in a Victorian's wardrobe. Yet they were absolutely essential. It is impossible to overstress the vastly greater quantity of walking which was required in nineteenth-century lives (as opposed to modern ones), and sturdy footwear was crucial. Horses required stabling space, care, and fodder, and were generally impractical for those living in cities. Carriages brought all the same problems as horses, compounded by the necessity of paying a coachman to drive and keep up the conveyance. Horse-pulled taxicabs did exist, but could be quite costly if used on a regular basis. The first bicycle was roughly contemporaneous with the first car, and it would be a number of years before either of them was considered to be anything other than a toy. Walking played a huge role in people's lives, and a good pair of boots was indispensable.

Nineteenth-century boots were far sturdier than their modern equivalents. This sturdiness had a (quite literal) price. Made by hand by skilled tradesmen, boots were one of the most expensive items in a Victorian's wardrobe. Yet they were absolutely essential. It is impossible to overstress the vastly greater quantity of walking which was required in nineteenth-century lives (as opposed to modern ones), and sturdy footwear was crucial. Horses required stabling space, care, and fodder, and were generally impractical for those living in cities. Carriages brought all the same problems as horses, compounded by the necessity of paying a coachman to drive and keep up the conveyance. Horse-pulled taxicabs did exist, but could be quite costly if used on a regular basis. The first bicycle was roughly contemporaneous with the first car, and it would be a number of years before either of them was considered to be anything other than a toy. Walking played a huge role in people's lives, and a good pair of boots was indispensable.

Hairpins, circa 1920

These two boxes of hairpins were acquired as new-old-stock. This quantity of hairpins (sold by weight) was originally marketed towards beauty salons.

Antique artifacts

(Clockwise, starting at left) Purple embroidered silk scarf, circa 1890; Post WWI souvenir handkerchief from France ("1919" -the date of the armistice- is embroidered in colors of the flags of the allied countries. This piece would have been brought home as a souvenir by a soldier returning home from war.); lady's lace handkerchief; peach-colored corset lace in original wrapping

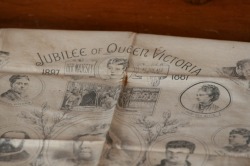

Souvenir Silk Handkerchief From Queen Victoria's Jubilee

Book locket

Victorian men wore more jewelry than their modern counterparts, and a popular place for ornamentation was the watch. This mother-of-pearl locket, designed to resemble a miniature book, hangs from the chain of a pocket-watch.

Gentleman's Top Hat with Box

Top hats were the quintessential elegant headpiece for respectable Victorian gentlemen. A gentleman would customarily tip his hat for a lady, and if you look closely in the photo above, you can see where the front brim of this particular hat is a bit worn from being grasped and tipped so many times. (He must have been a very polite man!)

Men's dress shoes

For everyday wear Victorian men customarily wore boots, but because these saw so much use very few have survived. Shoes like this would have been reserved for fancy dress occasions.

Men's Stick-Pins (Circa 1920's)

Stick-pins like these were worn to accent men's ties.

***

In a seaport town in the late 19th-century Pacific Northwest, a group of friends find themselves drawn together —by chance, by love, and by the marvelous changes their world is undergoing. In the process, they learn that the family we choose can be just as important as the ones we're born into. Join their adventures in

The Tales of Chetzemoka

Buy the book

|

First Wheel in Town:

|

Buy the book

|

Love Will Find A Wheel:

|

Buy the book

|

A Rapping At The Door:

|

Buy the book

|

Delivery Delayed:

|

Anthologies

***

Love's Messenger

|

The Wheelman's Joy

|

Victorian Cycles

Hand-built 1890's-style bicycles

Interested in a real time machine? Commission one of our 1890s-style custom bicycles! Custom, hand-made steel frames with wooden fenders and chainguards, leather saddles and cork grips. Whether you are interested in a roadster or a racer, we can build you the period bicycle of your dreams.

***

YouTube.com/@Victorianlady

Search this website:

***